Why VirusTotal is still the fastest external “second opinion” in the first hour

In real incident response, you don’t have time to debate philosophy. You need a repeatable way to answer:

- Is this artifact already known in the broader ecosystem?

- If it’s known, what else is it tied to (family, infra, behavior)?

- If it’s unknown, how do we reduce uncertainty without contaminating evidence or exposing private data?

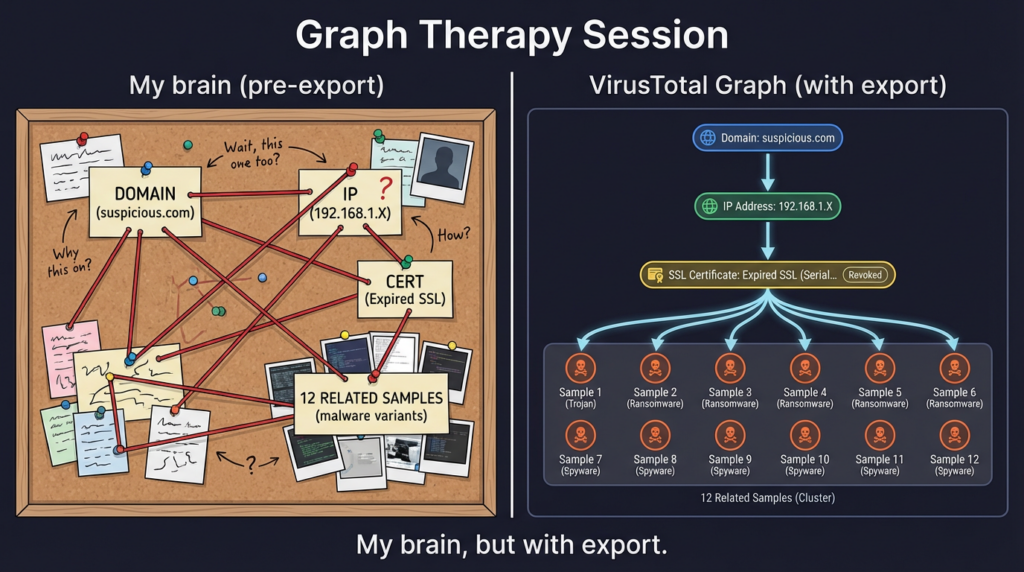

VirusTotal helps because it’s not only “multi-engine scanning.” It’s a dataset of entities (files, URLs, domains, IPs) that you can pivot across—especially with Graph, which is explicitly built to understand relationships and let you synthesize findings into a shareable threat map. (VirusTotal)

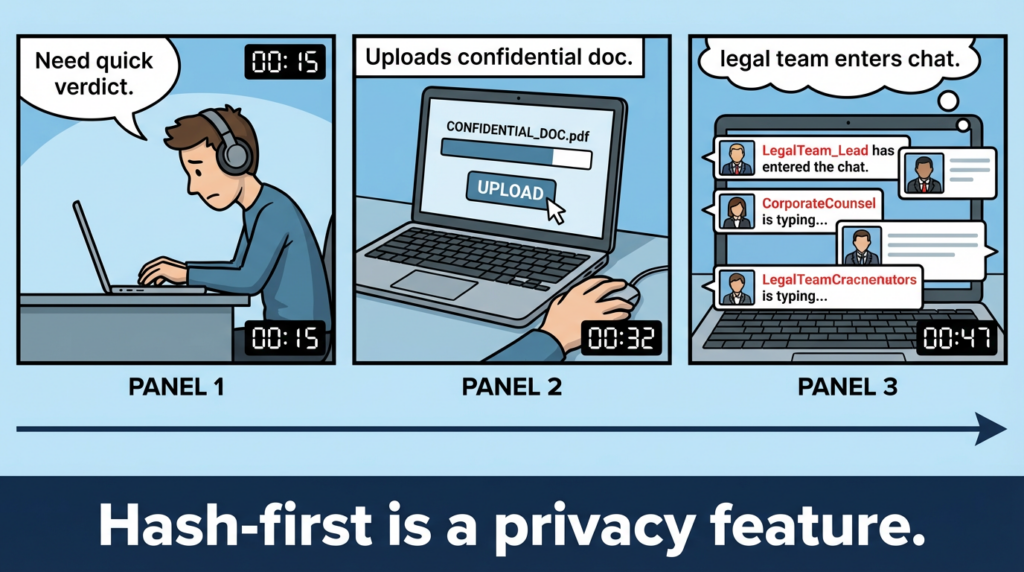

But that power comes with a non-obvious risk: the fastest way to “solve” a mystery is sometimes the fastest way to leak it. VirusTotal itself provides an “accidental upload” workflow and asks you to contact them if you uploaded something confidential. (VirusTotal)

So this article is written around one core principle:

Hash-first. Pivot-second. Upload-last (or never).

The search intents that drive the most real-world usage

If you’re writing or building a playbook around VirusTotal, the highest-intent usage clusters around what engineers actually do mid-incident:

- Hash lookup (SHA256/MD5/SHA1) to check whether something is already known

- URL checking for phishing / drive-by / payload hosting

- Domain & IP reputation and relationships to map infrastructure

- API v3 automation for enrichment pipelines

- Graph for relationship mapping across an investigation (VirusTotal)

- Intelligence search modifiers and behavior tags for hunting at scale (premium)

- Livehunt + YARA for continuous detection on new samples (VirusTotal)

This playbook follows that exact incident flow.

The incident-safe workflow you can standardize across your team

Step 0: Decide what is safe to query externally

Before anyone clicks “Upload,” classify what you’re about to send outside:

Typically safe

- Hashes (SHA256)

- Public domains/IPs

- URLs that are already public

- Filenames stripped of internal paths and user identifiers

High risk

- Internal documents, customer artifacts, email attachments

- Proprietary binaries (especially pre-release or customer-specific builds)

- Anything that might contain secrets (keys, tokens), PII, or contractual content

Why be strict? Because teams have repeatedly leaked confidential documents into public ecosystems by automating uploads or mishandling attachments. ThreatDown explicitly warns against automating uploads due to confidentiality risks. (ThreatDown by Malwarebytes) And Cisco Talos documented a macro-virus campaign that caused confidential documents to be uploaded to publicly accessible repositories, including VirusTotal-related workflows. (مدونة Cisco Talos Blog)

Policy you can write down: If a hash lookup answers the question, you did not need to upload the file.

Triage matrix: what to look up, what you get, what to do next

| What you have | What to do in VirusTotal | What you’re trying to learn | Next pivot |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHA256/MD5/SHA1 | Hash search / file report | Known vs unknown, detection stats, tags, timeline | Related URLs/domains/IPs; similar samples; Graph |

| URL | URL report | Redirects, detections, hosting patterns | Domain/IP report; certificate context; Graph |

| Domain | Domain report | Passive context, related URLs/files | IP/ASN neighborhood; related samples; Graph |

| IP | IP report | Hosting provider/ASN, related URLs/files | Domain cluster, infra reuse, Graph |

VirusTotal’s API model supports this entity-first thinking: the API v3 documentation covers authentication via an x-apikey header and entity endpoints like IP address reports. (VirusTotal)

Hash-first triage: the 5-minute check that prevents 5 hours of noise

What “good” looks like in the first pass

When you open a file report, your initial job is not to pick a side (“malicious” vs “clean”). Your job is to gather decision-grade signals:

- Analysis stats (how many vendors say malicious/suspicious/undetected)

- Timeline (first seen vs last seen)

- Tags / family hints (if present)

- Relationships (what URLs/domains/IPs it’s tied to)

- Behavior tags (if you have Intelligence access)

Do not treat “0/70 detected” as a pass. In targeted incidents, you often start with a sample that is new, packed, environment-specific, or simply under-reported.

What “bad” looks like

- Uploading the file because you want a quick answer (and accidentally exposing sensitive data)

- Treating the vendor count as a verdict rather than a feature

- Failing to pivot when relationships are the real story

Reading VirusTotal reports like an investigator, not an antivirus

Here’s the mental model that reduces false confidence:

1) Vendor disagreement is information

If one or two engines call a file “Generic Trojan” while the rest are silent, that’s not a reason to ignore it. It’s a reason to ask: “Is this a fresh dropper? Is it signed? Is it packed? Is it region-targeted?”

2) Time is a clue

A sample that appeared today and already has broad detections is often commodity. A sample that appeared today with low detections can be the start of your incident.

3) Relationships usually matter more than labels

A file tied to a known malicious URL, a newly registered domain, or a suspicious hosting cluster can be high-risk even when static detections lag.

4) Graph turns a pile of artifacts into a narrative

VirusTotal Graph is designed for exactly this: understand relationships between files/URLs/domains/IPs, pivot intelligently, and synthesize findings into a shareable threat map. (VirusTotal)

Pivoting tactics that actually work under time pressure

When you have one “seed” artifact, you want to expand scope fast without drowning.

Pivot ladder

File → URLs/domains/IPs

- If you only do one thing beyond hash lookup, do this.

- Your goal: find infrastructure you can block and additional artifacts you can search internally.

Domain → IP neighborhood

- Infra reuse is common. Even “one-off” campaigns reuse hosting patterns, certificates, or providers.

IP → related URLs/files

- IP reports can reveal additional payload paths, related samples, or clusters you didn’t know existed.

Everything → Graph

- Use Graph as the shared map: what’s central, what’s a one-off, what’s reused.

Intelligence hunting: search modifiers and behavior tags for “how far does this go”

If you have VirusTotal Intelligence, your posture changes from “lookup” to “query the dataset.”

VirusTotal maintains a full list of search modifiers and also documents behavior tag modifiers you can use to hunt based on sandbox-labeled behaviors. (VirusTotal) (Documentation hub) and (VirusTotal)

Practical advice: don’t try to memorize the full grammar. Build a small internal query cookbook around:

- file type, signatures/tags

- behavior tags

- time windows

- infra patterns (domains, netloc, ip ranges)

Livehunt + YARA: turn incident lessons into continuous detection

Livehunt exists so you can receive notifications when incoming samples match your YARA rules. VirusTotal’s Livehunt docs and the YARA guidance for Livehunt explain how to use the vt module to reference metadata like file type and analysis stats. (VirusTotal)

A minimal “triage signal” rule (not a family signature):

import "vt"

rule suspicious_pe_with_multiple_malicious_votes

{

condition:

vt.metadata.file_type == vt.FileType.PE_EXE and

vt.metadata.analysis_stats.malicious > 3

}

Use this kind of rule when your goal is early warning and queueing for analyst review—not attribution.

API v3 automation: enrichment without analyst burnout

The two lines you must get right

- You need a Community account and your personal API key is in settings. (VirusTotal)

- Authentication is done by including an

x-apikeyheader with your key in requests. (VirusTotal)

Minimal enrichment script pattern

This pattern is incident-safe if you only pass hashes/domains/IPs and avoid auto-uploads.

import os

import time

import requests

VT_API_KEY = os.environ["VT_API_KEY"]

HEADERS = {"accept": "application/json", "x-apikey": VT_API_KEY}

def vt_get(url: str, sleep_s: float = 1.2):

r = requests.get(url, headers=HEADERS, timeout=30)

if r.status_code == 429:

time.sleep(10)

r = requests.get(url, headers=HEADERS, timeout=30)

r.raise_for_status()

time.sleep(sleep_s)

return r.json()

def file_report(sha256: str):

return vt_get(f"<https://www.virustotal.com/api/v3/files/{sha256}>")

def domain_report(domain: str):

return vt_get(f"<https://www.virustotal.com/api/v3/domains/{domain}>")

def ip_report(ip: str):

return vt_get(f"<https://www.virustotal.com/api/v3/ip_addresses/{ip}>")

def summarize_file(j):

a = j["data"]["attributes"]

stats = a.get("last_analysis_stats", {})

return {

"malicious": stats.get("malicious", 0),

"suspicious": stats.get("suspicious", 0),

"undetected": stats.get("undetected", 0),

"harmless": stats.get("harmless", 0),

"first_submission_date": a.get("first_submission_date"),

"last_submission_date": a.get("last_submission_date"),

"tags": a.get("tags", [])[:10],

}

# Example:

# j = file_report("SHA256_HERE")

# print(summarize_file(j))

Bash examples you can copy into a terminal

# Hash search via entity endpoint

curl -sS \\

-H "accept: application/json" \\

-H "x-apikey: $VT_API_KEY" \\

"<https://www.virustotal.com/api/v3/files/REPLACE_WITH_SHA256>" | head

# IP report

curl -sS \\

-H "accept: application/json" \\

-H "x-apikey: $VT_API_KEY" \\

"<https://www.virustotal.com/api/v3/ip_addresses/8.8.8.8>" | head

VirusTotal’s API reference explicitly documents the authentication mechanism and the overall v3 overview. (VirusTotal)

Privacy and evidence handling: the section you want in your runbook

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: “quick upload” is often “quick disclosure.”

- VirusTotal provides an accidental upload workflow and asks users to contact them if they uploaded confidential information. (VirusTotal)

- ThreatDown argues you should not automate uploads because certain uploads can leak confidential data and organizations have done this without thinking through consequences. (ThreatDown by Malwarebytes)

- Private Scanning (Google Threat Intelligence / VirusTotal) exists specifically to allow analysis “in a privacy preserving fashion,” where files/URLs won’t be shared beyond your organization and analyses are ephemeral. (Google Threat Intelligence)

Practical runbook rules

- Hash lookups are permitted by default.

- Uploads require explicit approval and data classification checks.

- Automated uploading of email attachments is prohibited unless you can prove sensitive content cannot be uploaded.

Connecting VirusTotal findings to actively exploited CVEs

VirusTotal doesn’t “confirm a CVE.” It helps you map the real artifacts that exploitation produces: payload hashes, staging URLs, infrastructure, and adjacent samples.

Use CISA KEV as your prioritization input

CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog is meant to be used as an input to vulnerability management prioritization, and CISA issues alerts when it adds exploited items. (CISA)

In February 2026, CISA published an alert about adding six known exploited vulnerabilities to the KEV catalog. (CISA)

Practical playbook: exploit news → internal scope → VT enrichment → pivot → containment

- Start from KEV / patch coverage: list affected products and exploit vectors.

- Pull internal exposure: asset inventory + vulnerable versions + external surface.

- When you collect suspicious artifacts (file hashes, URLs, domains, IPs), enrich them in VirusTotal.

- Pivot to find more infra and related samples, then feed:

- blocklists (carefully, to avoid collateral)

- EDR detections (hash-based, behavior-based)

- SIEM queries (domain/IP contact, process tree patterns)

Example: Chrome zero-day CVE-2026-2441

Security reporting indicates Google issued an emergency update for Chrome to patch an actively exploited zero-day, CVE-2026-2441. (سيكيوريتي ويك)

In practice, browser exploitation often shows up as second-stage artifacts:

- newly downloaded payloads (hashes)

- suspicious outbound domains

- uncommon child processes or persistence attempts

VirusTotal is ideal for quickly understanding whether those second-stage artifacts resemble known clusters and to pivot for more IOCs.

If your team does both IR and security validation, VirusTotal and Penligent can complement each other without forcing a story:

- VirusTotal is strong for external context: “What is this artifact connected to out in the wild?” and “What else should we look for?”

- Penligent can be used for internal verification and path validation: once you suspect an entry vector or weak boundary, you can validate whether similar attack paths are reproducible in your environment and whether mitigations actually close the loop.

That division tends to reduce “intel theater” and move faster toward verified, testable risk.

A compact checklist you can paste into your incident channel

| المرحلة | الإجراء | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Triage | Hash lookup first | Known/unknown + stats |

| Expand | Pivot to URLs/domains/IPs | Candidate infra IOCs |

| التحقق من صحة | Cross-check internal telemetry | Scope + affected hosts |

| Contain | Block + quarantine + patch | Reduced blast radius |

| Hunt | Intelligence queries + behavior tags | Related artifacts |

| المراقبة | Livehunt YARA | Early warning for variants |

| Automate | API v3 enrichment | Repeatable pipeline |

Links

- Documentation hub: https://docs.virustotal.com/

- API v3 overview: https://docs.virustotal.com/reference/overview

- Getting started (API key): https://docs.virustotal.com/reference/getting-started

- Authentication (x-apikey header): https://docs.virustotal.com/reference/authentication

- Graph overview: https://docs.virustotal.com/docs/graph-overview

- Graph documentation: https://docs.virustotal.com/docs/graph-documentation

- Accidental upload guidance: https://docs.virustotal.com/docs/accidental-upload

- Private scanning: https://docs.virustotal.com/docs/private-scanning

- Private scanning (GTI docs): https://gtidocs.virustotal.com/docs/private-scanning

- CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog: https://www.cisa.gov/known-exploited-vulnerabilities-catalog

- CISA alert Feb 10, 2026 (adds six exploited vulnerabilities): https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/alerts/2026/02/10/cisa-adds-six-known-exploited-vulnerabilities-catalog

- SecurityWeek on Chrome zero-day CVE-2026-2441 (Feb 16, 2026): https://www.securityweek.com/google-patches-first-actively-exploited-chrome-zero-day-of-2026/Oal cautions about uploads

- ThreatDown: Why you shouldn’t automate VirusTotal uploads: https://www.threatdown.com/blog/why-you-shouldnt-automate-your-virustotal-uploads/

- Cisco Talos: OfflRouter campaign causing confidential documents to be uploaded: https://blog.talosintelligence.com/offlrouter-virus-causes-upload-confidential-documents-to-virustotal/

- https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/is-getintopc-safe-the-real-security-malware-and-legal-risk-profile/

- https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/the-hidden-architecture-of-compromise-an-exhaustive-security-analysis-of-getintopc/

- https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/es/the-openclaw-prompt-injection-problem-persistence-tool-hijack-and-the-security-boundary-that-doesnt-exist/