Security engineers are not suddenly searching Partial Prerendering (PPR) because they became frontend performance enthusiasts overnight.

In practical terms, PPR works by sending a prerendered static shell first and then streaming dynamic sections into the page as the server resolves them. Next.js now describes this model under Cache Components and explicitly calls it Partial Prerendering. (Nächste.js)

That sounds elegant, and often it is. But from a security perspective, it also means you are no longer reviewing “a page render” as one unit. You are reviewing a Shell, streamed fragments, component-level caching behavior, and sometimes resume endpoints that can become new attack surfaces. Recent Next.js advisories make that concrete, not hypothetical. (Vercel)

This article focuses on the security reasons PPR is getting attention, without losing the engineering reality: PPR can be a strong architectural choice, but only if teams treat it as a security-sensitive rendering model, not just a Core Web Vitals optimization.

What Partial Prerendering Actually Changes

The common definition of PPR is accurate but incomplete:

PPR prerenders a static shell and streams dynamic content later.

The missing piece is what that implies operationally. With PPR-style rendering, the page is no longer governed by a single rendering strategy such as SSR or SSG. Instead, different parts of the same route can be:

- prerendered now,

- cached and reused,

- or deferred to request time behind Suspense boundaries.

The Next.js Cache Components docs describe exactly this: mixing static, cached, and dynamic content in one route, with a shell sent immediately and dynamic UI updating as data becomes available. The docs also state this rendering approach is called Partial Prerendering. (Nächste.js)

For product and performance teams, this is powerful.

For security teams, it means the application’s behavior becomes more compositional—and compositional systems are where subtle security bugs thrive.

Why Security Engineers Are Paying Attention Now

The recent interest is not random. It maps to three categories of risk that matter in real environments:

- Availability risk from PPR-related request handling paths in self-hosted Next.js deployments

- CSP architecture conflicts, especially with nonce-based CSP strategies used to harden against XSS

- State and data boundary confusion introduced by streaming, deferred rendering, and component-level caching

The first two are directly documented in authoritative sources today. The third is best treated as an engineering risk class that demands validation, not as a blanket claim that PPR is inherently unsafe.

That distinction matters, because serious teams need precision.

The DoS Problem That Put PPR on Security Teams’ Radar

The most concrete trigger for recent security attention was a publicly disclosed Next.js denial-of-service issue affecting PPR under specific self-hosted conditions.

Vercel’s January 2026 changelog summary for CVE-2025-59472 describes a DoS vulnerability in Next.js applications when Partial Pre-Rendering is enabled and the app is running in minimal mode. The summary explains that the PPR resume endpoint accepts unauthenticated POST requests and processes attacker-controlled postponed state data, and that memory exhaustion can occur due to unbounded request buffering or decompression. (Vercel)

GitHub’s advisory for the same issue provides the same core description and emphasizes that the endpoint accepts unauthenticated requests marked with the Next-Resume: 1 header in affected setups. (GitHub)

Why this matters beyond one CVE

This incident is important not just because of the vulnerability itself, but because of what it reveals about PPR in production:

- PPR introduces additional protocol behavior (resume/postponed state handling)

- Those code paths may sit behind different proxy and middleware assumptions

- Self-hosted deployments may not inherit the same hardening as managed hosting environments

Vercel explicitly noted that these disclosed issues did nicht affect applications hosted on Vercel’s platform, while self-hosted Next.js deployments needed patching or mitigation. That is a crucial operational boundary for defenders. (Vercel)

A note on naming and CVE references

You mentioned “CVE-2026-0963 and similar variants.” The widely documented Next.js PPR-related DoS disclosure tied to resume endpoint memory exhaustion is CVE-2025-59472 (with related memory-exhaustion disclosure CVE-2025-59471 covering a different Next.js image optimizer path). I’m using the publicly documented identifiers to keep the article precise. (Vercel)

How the PPR Resume Endpoint Changes the Threat Model

The security lesson here is broader than “patch your framework.”

When your frontend rendering model introduces a resume mechanism that accepts attacker-reachable POST traffic, you now have a path that behaves more like an API endpoint than a traditional document request. If request-body buffering, decompression limits, or reverse-proxy protections are not configured tightly, availability becomes fragile.

That is exactly the pattern described in the advisory: unauthenticated requests with attacker-controlled postponed state can trigger memory pressure severe enough to terminate the Node.js process. (GitHub)

For large organizations, that is not just a developer inconvenience. It is an uptime and incident-response issue:

- application downtime

- crash-loop behavior under repeated traffic

- autoscaling cost spikes

- alert fatigue and false incident classification

- defensive confusion if teams assume “it’s just a page endpoint”

PPR did not invent DoS. But it created a new place where DoS defenses need to be explicit.

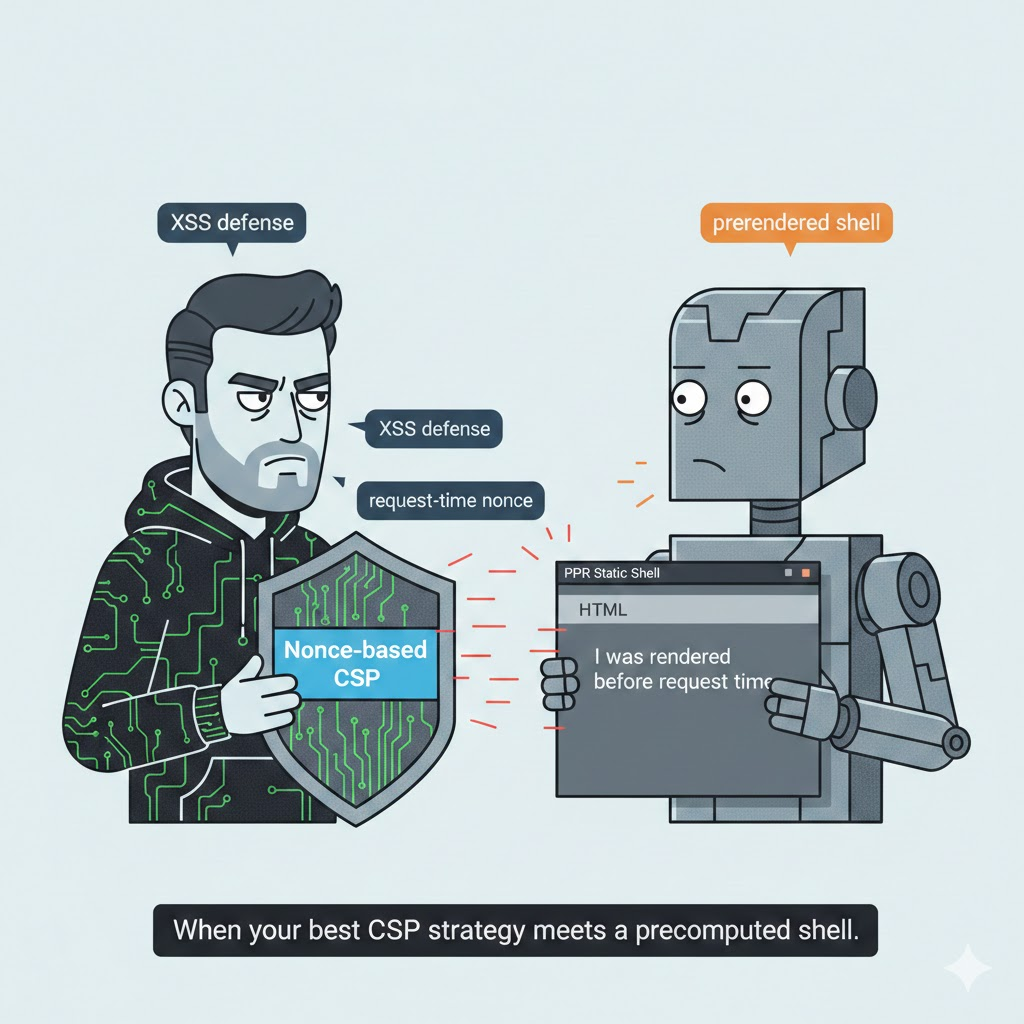

Two-character meme in serious cybersecurity illustration style.

Character 1: “Security Engineer” holding a shield labeled “Nonce-based CSP”.

Character 2: “PPR Static Shell” holding a prebuilt HTML block saying “I was rendered before request time.”

Both stare at each other in awkward silence.

Small floating labels: “XSS defense”, “request-time nonce”, “prerendered shell”.

Caption: “When your best CSP strategy meets a precomputed shell.”

Minimal, professional, slightly humorous, dark mode UI accents.

Two-character meme in serious cybersecurity illustration style.

Character 1: “Security Engineer” holding a shield labeled “Nonce-based CSP”.

Character 2: “PPR Static Shell” holding a prebuilt HTML block saying “I was rendered before request time.”

Both stare at each other in awkward silence.

Small floating labels: “XSS defense”, “request-time nonce”, “prerendered shell”.

Caption: “When your best CSP strategy meets a precomputed shell.”

Minimal, professional, slightly humorous, dark mode UI accents.

Why Nonce-Based CSP and PPR Clash in Practice

The second reason security engineers care is even more painful for mature organizations: PPR can conflict with strong CSP deployments.

This is not forum speculation. The Next.js CSP guide explicitly states that Partial Prerendering is incompatible with nonce-based CSP, because static shell scripts will not have access to the per-request nonce. The docs also outline the broader performance and caching implications of nonce-based CSP, including disabling static optimization and ISR in the nonce-driven rendering model. (Nächste.js)

That one sentence has enormous consequences.

Why the conflict is structural, not incidental

Nonce-based CSP depends on a per-request random value inserted into the HTML and applied to inline scripts or script tags. That nonce exists only at request time.

PPR’s core optimization is that part of the HTML shell is prerendered ahead of the request.

Those two design goals collide:

- CSP nonce wants request-time uniqueness

- PPR shell wants precomputed output

This is why security teams see PPR as an architecture decision, not a toggle.

The real security pressure this creates

Organizations that have invested in strict CSP to reduce XSS exploitability (especially with nonce-based script-src) may face uncomfortable choices:

- disable or avoid PPR on sensitive routes

- redesign script loading strategy

- explore alternatives such as hash/SRI-based approaches where feasible

- split architecture by route sensitivity rather than enforcing one rendering model everywhere

The Next.js docs also mention experimental Subresource Integrity support as an alternative pattern in some cases, but they present it as experimental and with constraints. Teams should treat that as design work, not an instant replacement. (Nächste.js)

MDN’s CSP guidance remains relevant here: CSP is still a major defense-in-depth control for XSS and other browser-side risks. If adopting PPR weakens your CSP posture, that tradeoff must be documented and justified. (MDN-Webdokumente)

The Data Flow and State Integrity Risk People Are Really Worried About

The third concern is often described loosely as “state hijacking” or “stream metadata tampering.” That wording can become speculative fast, so it helps to restate the issue more precisely.

PPR and related streaming architectures involve transferring deferred render state and streamed updates between server and client. Security engineers worry about three classes of mistakes:

- Cache scope mistakes A component assumed to be cacheable accidentally includes user-specific or tenant-specific data.

- Boundary leakage Sensitive data appears in the prerendered shell or fallback UI when it should only appear in a request-time authenticated fragment.

- Stream/metadata robustness failures The application fails unsafely when deferred state, resume data, or streamed payloads are malformed, replayed, or unexpectedly large.

The recent DoS advisory gives us a confirmed example of category #3 in the availability dimension (malicious postponed state causing memory exhaustion). (GitHub)

For confidentiality and integrity concerns, the risk is often not “PPR protocol compromise” in a cinematic sense. It is usually simpler and more common: application logic and caching boundaries were designed incorrectly.

That is still dangerous, and it is exactly why security teams are paying attention.

PPR Is a Performance Feature, but It Also Moves Security Boundaries

A useful way to evaluate PPR is to stop thinking in terms of “frontend vs security” and start thinking in terms of boundary movement.

PPR changes at least four boundaries:

| Boundary | Before | After PPR | Auswirkungen auf die Sicherheit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Render timing | More route-level | More component-level | More chances to mis-scope data |

| Request handling | Fewer specialized paths | Resume/stream/deferred paths may appear | New DoS and parsing surfaces |

| Caching scope | Route/page cache often dominates | Component-level cache decisions matter more | Cross-user leakage risk increases if misconfigured |

| CSP assumptions | SSR/fully dynamic can support nonce flow more naturally | Prerendered shell cannot carry per-request nonce | Strong nonce-based CSP may conflict |

This is why a performance team can roll out PPR and honestly report a speed improvement while a security team simultaneously reports increased risk. Both can be correct.

How to Use PPR Without Breaking Your Security Posture

PPR is not something to avoid categorically. It is something to deploy deliberately.

The strongest pattern is to classify page content into three groups before touching code:

- Must be visible immediately and is safe to prerender

- Can be cached safely within a defined scope

- Must remain request-time dynamic and non-cacheable

If a team cannot clearly classify a component, that component should default to the stricter path.

What should almost never be in a broadly cacheable fragment

- user name or profile metadata

- access tokens or session-derived strings

- tenant-scoped controls without explicit partitioning

- entitlement flags

- security-sensitive notifications

- debug or environment data

What fallback UI must not leak

Fallbacks are often treated as harmless placeholders, but in PPR they are part of the shell and may be visible before authentication-bound content resolves.

Avoid fallbacks like:

- “Loading premium admin secrets…”

- “Loading internal SOC alerts…”

- “Fetching user token…”

That seems obvious when written out, but production placeholders frequently encode exactly the wrong assumptions.

A Minimal Defensive Example for a PPR-Friendly Page

This example is intentionally simple. The point is not framework syntax perfection; it is boundary discipline.

import { Suspense } from "react";

import { cookies } from "next/headers";

// Safe to prerender: public shell

export default function SecurityStatusPage() {

return (

<main>

<h1>Platform Security Status</h1>

<p>Current incident posture and public service availability.</p>

{/* Public status summary can be cached if truly non-user-specific */}

<publicstatussummary />

{/* User-specific content must stay dynamic */}

<suspense fallback="{<UserPanelFallback" />}>

<usersecuritypanel />

</Suspense>

</main>

);

}

async function PublicStatusSummary() {

"use cache"; // only if the response is truly safe to share in scope

const res = await fetch("<https:>", {

next: { revalidate: 60 },

});

if (!res.ok) throw new Error("Failed to load public status");

const data = await res.json();

return (

<section>

<h2>Public Status</h2>

<p>Services operational: {data.operational}</p>

<p>Open incidents: {data.openIncidents}</p>

</section>

);

}

async function UserSecurityPanel() {

const cookieStore = await cookies();

const session = cookieStore.get("session")?.value;

const res = await fetch("<https:>", {

headers: { Authorization: `Bearer ${session}` },

cache: "no-store",

});

if (!res.ok) throw new Error("Failed to load user panel");

const data = await res.json();

return (

<section>

<h2>My Security Actions</h2>

<ul>

{data.actions.map((a: any) => <li key="{a.id}">{a.title}</li>)}

</ul>

</section>

);

}

function UserPanelFallback() {

// Keep fallbacks generic; do not expose privileged context

return (

<section>

<h2>My Security Actions</h2>

<p>Loading your data…</p>

</section>

);

}

The key security ideas here are simple:

- public summary is cacheable only if it is truly public

- user panel is explicitly request-time and non-cacheable

- fallback UI is generic and non-sensitive

Those choices matter more than whether a team can recite the PPR definition.

What to Patch and What to Harden Right Now

If you run self-hosted Next.js and use PPR-related functionality, there are two parallel actions:

1) Patch framework versions covered by advisories

Vercel’s January 2026 summary for CVE-2025-59472 and CVE-2025-59471 includes affected and fixed version guidance. Use that as your source of truth for triage and upgrade planning. (Vercel)

2) Harden the infrastructure path, even after patching

The advisory context makes it clear that request buffering and decompression behavior matter. Defensive controls should include:

- request body size limits at reverse proxy

- buffering limits

- decompression limits / safeguards

- rate limiting on unauthenticated endpoints

- timeouts for abnormal request behavior

- endpoint observability for resume/stream-related paths

Patches close known vulnerabilities. Hardening reduces the blast radius of unknown ones.

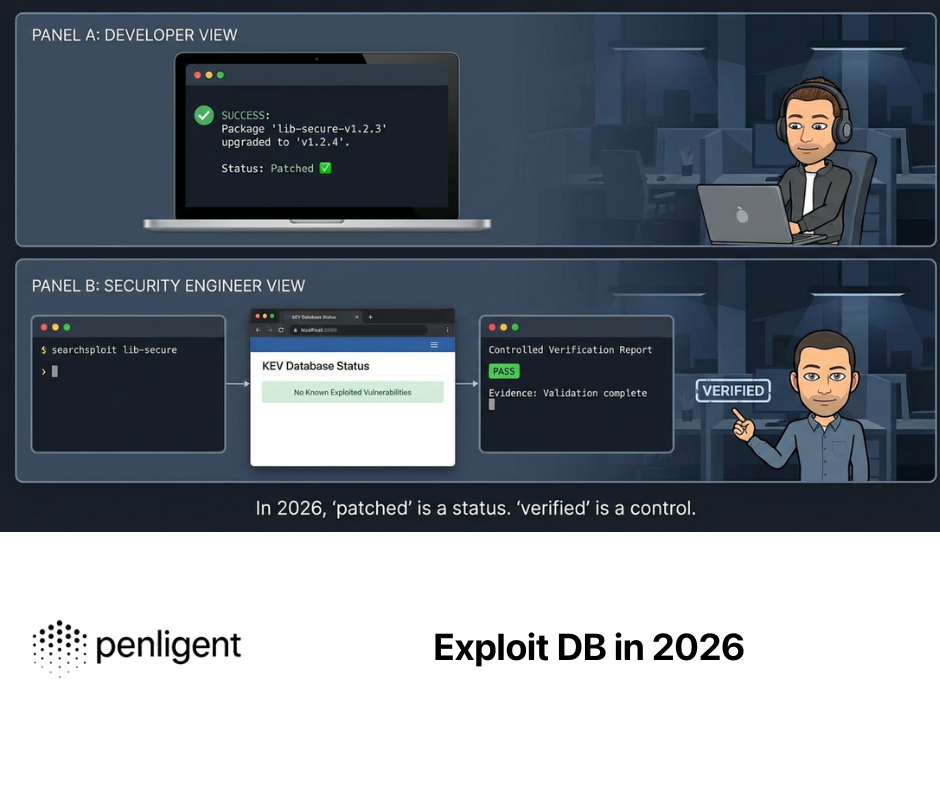

Why AI-Driven Pentesting Is Crucial for Modern Architectures like PPR

Modern architectures like PPR are difficult to secure because the risks are no longer concentrated in one obvious place.

A traditional manual review might look at:

- route auth checks,

- API handlers,

- and CSP headers.

That is still necessary, but it is not sufficient when rendering behavior is split across shell output, deferred fragments, cached components, and runtime-specific endpoint flows.

This is exactly where AI-assisted pentesting workflows become useful—not as a replacement for human judgment, but as a way to systematically validate more states, more paths, and more boundary assumptions than teams typically cover in a single sprint.

For PPR-like architectures, the most valuable testing focus is not “spray generic payloads everywhere.” It is targeted validation of the architecture’s new fault lines:

- cache-scope verification across user/tenant contexts

- streaming and deferred endpoint abuse testing for size, decompression, and malformed payload handling

- fallback and shell leakage checks for accidental sensitive content exposure

- CSP regression testing after rendering-mode changes

- dynamic fragment isolation checks to verify request-bound data never becomes reusable output

That is where a platform like Penligent can fit naturally in a modern engineering workflow: not by claiming PPR is insecure by default, but by helping teams produce evidence that a performance-driven rendering change did not create a new exposure path.

The practical win is not just “we scanned it.” The win is that security, platform, and frontend teams can converge on a repeatable validation routine for an architecture that is otherwise easy to misjudge by eyeballing code or relying on framework defaults.

What Security Teams Should Ask Before Approving PPR on a Route

These questions are far more useful than “Do we support PPR?”

Content and data questions

- Which content is entity-defining and must appear in the shell?

- Which content is personalized and must remain request-time?

- Which fragments are cacheable, and what is the cache key scope?

CSP questions

- Do we require nonce-based CSP on this route?

- If yes, are we prepared to disable PPR or redesign script strategy?

- If no, what is the compensating control plan?

Availability and abuse questions

- Does this deployment expose resume/stream-related endpoints?

- Are unauthenticated request body limits and decompression limits enforced at the proxy?

- Are we monitoring memory pressure and crash-loop signals tied to these endpoints?

Validation questions

- Have we tested cross-user leakage with synthetic multi-account flows?

- Have we tested malformed or oversized payload behavior where applicable?

- Have we measured field performance improvements to justify the architecture change?

Those questions force teams to treat PPR as an engineering system, not a marketing feature.

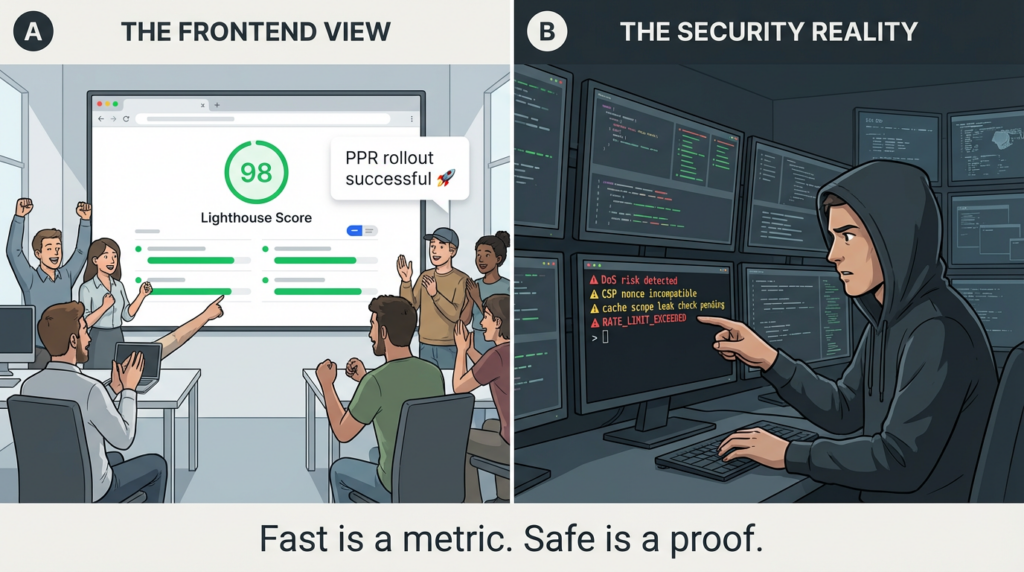

Performance Wins Are Real, but Security Debt Can Hide Inside Them

It is worth stating clearly: PPR can improve user-perceived performance and delivery efficiency by reducing full-route blocking and sending useful HTML earlier. That aligns with the general performance guidance around server responsiveness and early content delivery, which affects downstream metrics like FCP and LCP. (web.dev)

But performance wins can mask security regressions if teams stop at Lighthouse screenshots.

Security engineers are right to scrutinize PPR because it sits at the intersection of:

- rendering,

- caching,

- request parsing,

- and browser policy enforcement.

That is exactly where subtle failures become costly.

The Practical Bottom Line for Security Engineers

Partial Prerendering is not just a frontend optimization topic anymore.

It is a modern web architecture topic with direct security implications:

- a documented DoS case in self-hosted Next.js PPR-related flows under specific conditions (Vercel)

- a documented incompatibility with nonce-based CSP in Next.js PPR scenarios (Nächste.js)

- and a broader class of cache-boundary and data-boundary mistakes that require deliberate validation

The right response is not fear or blind adoption.

The right response is disciplined rollout:

- patching,

- proxy hardening,

- boundary-aware design,

- CSP-aware route strategy,

- and continuous validation of dynamic behavior.

That is why security engineers are searching Partial Prerendering (PPR) right now. They are not chasing a trend. They are doing what they should do whenever a framework changes how data moves through a page: re-drawing the threat model before the attackers do.

Suggested References and Further Reading

- Next.js Cache Components docs (PPR behavior and shell/stream model) (Nächste.js)

- Next.js CSP guide (nonce-based CSP incompatibility with PPR) (Nächste.js)

- Vercel security summary for CVE-2025-59471 and CVE-2025-59472 (Vercel)

- GitHub security advisory (GHSA-5f7q-jpqc-wp7h) for PPR DoS details (GitHub)

- NVD entry for CVE-2025-59472 (NVD)

- MDN CSP guide and CSP header reference (MDN-Webdokumente)

- OWASP CSP Cheat Sheet (defense-in-depth framing) (OWASP-Spickzettel-Serie)

- web.dev TTFB and INP guidance for evaluating delivery changes (web.dev)

- Penligent Hacking Labs index (recent security writeups) (Sträflich)

- Penligent Hacking Labs archive pages (recent articles overview) (Sträflich)

- Example Penligent CVE writeups showing a “verify, don’t assume” response style (e.g., CVE-2026-2441 coverage) (Sträflich)