What Apple actually disclosed

Apple’s security notes for iOS/iPadOS 26.3 describe CVE-2026-20700 as a memory corruption issue addressed with “improved state management,” with the impact: “An attacker with memory write capability may be able to execute arbitrary code.” Apple also states it is aware of a report the issue may have been exploited in an “extremely sophisticated attack” against targeted individuals on iOS versions prior to iOS 26. (Soporte técnico de Apple)

The same core wording appears across Apple platforms, including macOS Tahoe 26.3. (Soporte técnico de Apple)

Two immediate implications for defenders:

- This is not presented as a one-click remote takeover by itself. The phrase “with memory write capability” is a huge qualifier. It usually means the attacker already has a primitive like arbitrary write or controlled memory corruption earlier in the chain, and CVE-2026-20700 helps turn that foothold into reliable code execution (or makes the chain stable across more devices).

- It’s still a “drop everything” patch for high-risk populations and managed fleets because Apple says exploitation was real (in targeted attacks), and CISA placed it in the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog. (CISA)

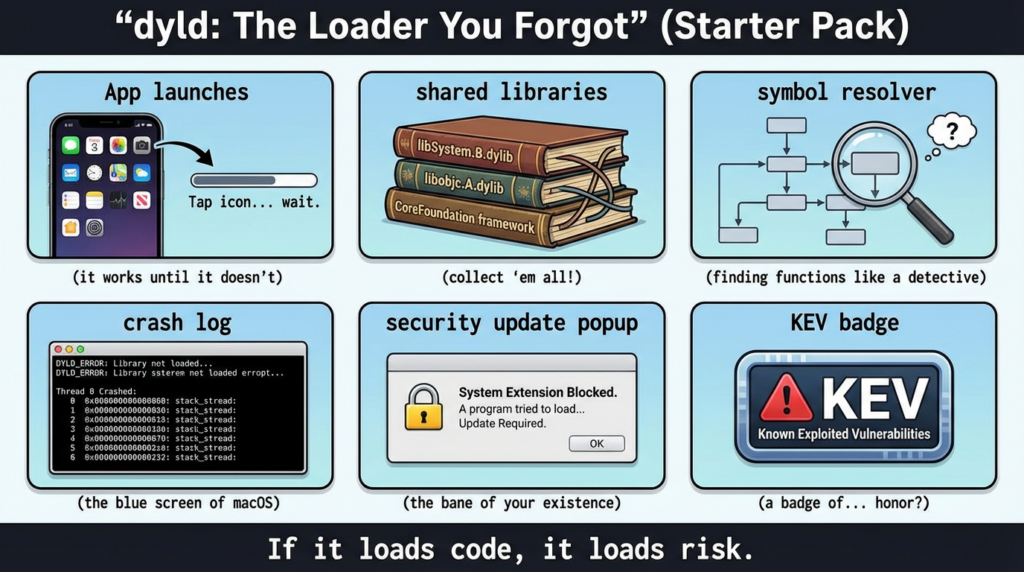

CVE-2026-20700 in plain English: dyld as a leverage point

dyld (the Dynamic Link Editor) is the loader that maps shared libraries into a process and resolves symbols at runtime. If an attacker can influence dyld’s state while also holding a memory-write primitive, dyld becomes a powerful pivot: it sits on critical execution paths and can be abused to redirect control flow.

Apple’s description is intentionally non-specific (as usual for in-the-wild chains), but the security content makes three things clear:

- The bug class is memory corruption. (NVD)

- The precondition is memory write capability. (Soporte técnico de Apple)

- Exploitation was associated with a campaign serious enough that Apple used its strongest public language: “extremely sophisticated” and “specific targeted individuals.” (Soporte técnico de Apple)

Also noteworthy: Apple credits Google Threat Analysis Group for reporting CVE-2026-20700. (Soporte técnico de Apple) That’s a recurring signal in spyware-grade incidents: research teams that track state-backed operations tend to surface the kinds of bugs you no see in commodity campaigns.

The bigger story: why CVE-2026-20700 is discussed alongside two earlier WebKit zero-days

Apple explicitly references CVE-2025-14174 y CVE-2025-43529 in the CVE-2026-20700 advisories as related issues “issued in response” to the same report. (Soporte técnico de Apple)

Those two CVEs are WebKit issues from Apple’s earlier releases:

- CVE-2025-43529: a WebKit use-after-free that can lead to arbitrary code execution when processing maliciously crafted web content. (NVD)

- CVE-2025-14174: a WebKit memory corruption issue, also described in Apple’s security content as exploited in the same class of targeted attacks. (Soporte técnico de Apple)

This is how defenders should interpret that trio, without overclaiming details Apple didn’t publish:

- WebKit is a common entry point for targeted iOS infection chains (message → web content → browser engine).

- Once initial code execution is achieved in a constrained process, attackers typically need additional steps to escape sandboxes, gain deeper privileges, or achieve persistence.

- A dyld-related primitive that helps convert “memory write” into “arbitrary code execution” can be the kind of reliability upgrade that makes an advanced chain work across more OS builds.

A number of public reports framed CVE-2026-20700 as part of a chained infection path with the WebKit issues. For example, Malwarebytes explicitly describes it as used “as part of an infection chain combined with CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529” against iOS versions prior to iOS 26. (Malwarebytes)

That’s a plausible read of Apple’s own cross-references, but it remains a defender inference, not a vendor-published step-by-step exploit chain.

What’s affected and what’s fixed: the versions that matter in production

Apple’s security content and NVD entries converge on the same “fixed in” releases:

- iOS / iPadOS 26.3

- macOS Tahoe 26.3

- tvOS 26.3

- watchOS 26.3

- visionOS 26.3 (NVD)

CISA KEV lists CVE-2026-20700 and shows a remediation due date (KEV deadlines matter for federal and often cascade into enterprise SLAs). (CISA)

Patch mapping table (operational view)

| Plataforma | Fixed version(s) called out in advisories | What you should do in practice |

|---|---|---|

| iOS / iPadOS | 26.3 (Apple security content) (Soporte técnico de Apple) | Enforce minimum OS = 26.3 via MDM compliance; prioritize high-risk users first |

| macOS | macOS Tahoe 26.3 (Soporte técnico de Apple) | Enforce OS updates; verify at scale via inventory + compliance |

| watchOS / tvOS | 26.3 (Soporte técnico de Apple) | Update where managed; treat as part of “whole ecosystem” risk reduction |

| visionOS | 26.3 (via NVD “fixed in” list) (NVD) | Update if in use; include in asset inventory and vulnerability reporting |

If you only take one lesson from Apple’s multi-platform “fixed in” lists: attackers don’t care which Apple device is the easiest stepping stone in your environment. Your security posture is the minimum patch level across the ecosystem.

Why this belongs on your “top risk” list even if you’re not a typical iOS-target

The most common mistake enterprises make with “targeted individual” language is to downgrade it as irrelevant.

Three reasons that’s risky:

- Targeted chains spill over. The moment an exploit chain becomes reliable, it gets re-used. Sometimes it’s still “targeted,” but the set of targets grows (executives, legal, finance, corp dev, incident responders, anyone with access).

- Your org’s risk isn’t just “nation-state vs not.” It’s also: do you have high-value Apple endpoints, do you have privileged users on iOS/macOS, do you have sensitive comms, and do you have a BYOD program with weak compliance?

- CISA KEV is a forcing function. Even if you personally doubt your exposure, KEV means there is credible evidence of exploitation in the wild. (CISA)

Fleet verification that doesn’t rely on vibes

You want something you can put in a ticket, a dashboard, and an audit report.

macOS: quick local verification

# macOS version

sw_vers

# Kernel version (sometimes useful when correlating crash/telemetry)

uname -a

macOS: osquery inventory queries (example)

-- macOS version inventory

SELECT

hostname,

version,

build,

platform

FROM os_version;

-- Installed apps inventory (useful for correlating Apple platform assets)

SELECT

name,

bundle_identifier,

version

FROM apps

WHERE bundle_identifier LIKE 'com.apple.%';

MDM compliance approach (conceptual, vendor-agnostic)

- Define minimum OS versions:

- iOS/iPadOS ≥ 26.3

- macOS Tahoe ≥ 26.3

- Block access to sensitive resources (email, VPN, SSO) if below minimum.

- Add a “high-risk exception” workflow for execs: immediate patch + device check-in.

This is boring by design. If your verification process needs heroics, it won’t survive the next zero-day.

Incident response: what you can do when you suspect targeted exploitation

Because Apple doesn’t publish public IOCs for most spyware-grade chains, you need an IR plan that assumes low signal, high impact.

Practical triage goals

- Confirm device versions at the time of suspected exposure.

- Identify users who received suspicious content and correlate timelines.

- Escalate quickly for high-risk identities (execs, security, legal, journalists, diplomats, researchers).

- Preserve artifacts where feasible (for macOS, this is easier; for iOS, you may need specialized tooling and lawful processes).

A reality check on telemetry

- On iOS, you often won’t get the kind of forensic depth you expect from endpoints.

- On macOS, you can collect richer logs and endpoint telemetry—but sophisticated attackers aim to be quiet.

So your best “defensive ROI” is often: patch fast, enforce compliance, and reduce attack surface for high-risk users.

Prioritization model: how to rank CVE-2026-20700 inside your backlog

When teams argue about priorities, it helps to make the scoring explicit.

| Factor | CVE-2026-20700 signal |

|---|---|

| Exploited in the wild | Yes (Apple language; KEV listing) (Soporte técnico de Apple) |

| Cross-platform blast radius | iOS, iPadOS, macOS, watchOS, tvOS, visionOS (NVD) |

| Exploit preconditions | “Memory write capability” (suggests chain) (Soporte técnico de Apple) |

| Likely target profile | “Specific targeted individuals” (spyware-grade) (Soporte técnico de Apple) |

| Enterprise mitigation | Strong (patch + compliance) |

| Verificación | Straightforward (OS versions) |

The key is: even if it’s chained, the mitigation is simple and high confidence. That’s the dream scenario. Don’t waste it.

Related CVEs you should mention in the same breath (because defenders search this way)

If your readers are searching “CVE-2026-20700 exploit chain,” they are almost certainly also searching:

- CVE-2025-14174 (WebKit memory corruption; referenced by Apple as related) (Soporte técnico de Apple)

- CVE-2025-43529 (WebKit use-after-free leading to code execution; referenced as related) (NVD)

This isn’t about stuffing extra CVE IDs into an article. It’s about matching how engineers actually triage: “What else is part of the same campaign? What else should I patch if I’m already touching iOS?”

If your organization is already using Penligente (or evaluating it), CVE-2026-20700 is a clean example of a broader pattern: modern security teams don’t just need “patch guidance”—they need repeatable proof that remediation is complete and drift stays controlled.

Penligent’s value in that workflow isn’t pretending it can “scan iPhones.” It’s helping you:

- turn advisories into verification checklists that map to real assets,

- generar informes basados en pruebas for leadership (“% compliant, exceptions, deadlines, risk justification”),

- and integrate endpoint and web exposure validation into one operational rhythm, so “zero-day response” doesn’t become an ad-hoc fire drill every month.

If you want that approach to feel credible, keep it strict: Penligent supports the proceso (asset discovery, validation workflows, reporting), while MDM/endpoint management enforces the actual patch compliance.

The takeaway security teams should internalize

CVE-2026-20700 is not interesting because it’s “dyld” or because it sounds exotic.

It’s interesting because Apple’s own language tells you it was used in serious real-world targeting, and the fix is the kind defenders can actually operationalize: update, enforce, verify.

If you’re tired of vulnerabilities that require guessing, CVE-2026-20700 is refreshingly binary:

- Are you on fixed versions (26.3) or not?

- Do you enforce compliance or merely recommend it?

- Do you have an exception process that protects high-risk users, or a spreadsheet that nobody reads?

Referencias

- Apple iOS 26.3 / iPadOS 26.3 security content (CVE-2026-20700) https://support.apple.com/en-us/126346

- Apple macOS Tahoe 26.3 security content (CVE-2026-20700) https://support.apple.com/en-us/126348

- NVD entry: CVE-2026-20700 https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-20700

- CVE.org record: CVE-2026-20700 https://www.cve.org/CVERecord?id=CVE-2026-20700

- CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) Catalog https://www.cisa.gov/known-exploited-vulnerabilities-catalog

- BleepingComputer coverage of CVE-2026-20700 https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/apple-fixes-zero-day-flaw-used-in-extremely-sophisticated-attacks/

- Malwarebytes write-up (chain discussion) https://www.malwarebytes.com/blog/news/2026/02/apple-patches-zero-day-flaw-that-could-let-attackers-take-control-of-devices

- CVE-2026-21510 PoC: The SmartScreen Moment That Never Happens https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-21510-poc-the-smartscreen-moment-that-never-happens/

- CVE-2026-1868 GitLab AI Gateway RCE: The Anatomy of an AI Breach https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-1868-gitlab-ai-gateway-rce-the-anatomy-of-an-ai-breach/

- Notepad RCE: When a “Lightweight App” Learns Markdown, It Inherits Browser-Sized Risk https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/notepad-rce-when-a-lightweight-app-learns-markdown-it-inherits-browser-sized-risk/

- CVE-2026-20841 PoC: When Notepad Learns Markdown, a Click Can Become Execution https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-20841-poc-when-notepad-learns-markdown-a-click-can-become-execution/