Les sites WordPress sont implacablement ciblés au niveau de la couche de connexion. La raison en est simple : l'authentification est un point d'étranglement universel, et l'authentification n'est pas un problème. wp-login.php est prévisible sur des millions de déploiements. Lorsque les attaquants automatisent à grande échelle - bourrage d'identifiants, pulvérisation de mots de passe, devinettes distribuées - la question n'est pas de savoir si votre site sera sondé, mais si vos défenses sont conçues pour résister à une pression réelle.

Ce guide s'adresse aux validation de sécurité autorisée et ingénierie défensive. Il se concentre sur la manière de modéliser en toute sécurité le comportement réaliste d'un attaquant, de mesurer la résilience et de renforcer l'authentification de WordPress d'une manière efficace, observable et durable sur le plan opérationnel.

A quoi ressemblent les "attaques réalistes de connexion à WordPress" dans la nature ?

La plupart des compromissions de WordPress qui commencent à la connexion ne reposent pas sur des vulnérabilités exotiques. Elles reposent sur des considérations économiques :

Remplissage de documents d'identité : les attaquants rejouent les paires nom d'utilisateur/mot de passe divulguées lors de brèches précédentes, en pariant sur la réutilisation des mots de passe.

Pulvérisation du mot de passe : les attaquants essaient d'utiliser un petit nombre de mots de passe communs à de nombreux comptes pour éviter les blocages.

Devinettes distribuées : Les tentatives sont réparties sur plusieurs IP et fenêtres temporelles afin de contourner les limites de taux de base.

Pression de disponibilité : l'objectif de l'attaquant peut être le temps d'indisponibilité, et non l'épuisement des travailleurs PHP ou des connexions à la base de données.

L'idée la plus importante : une "force brute bruyante" à partir d'une seule adresse IP n'est pas la menace la plus réaliste. Les campagnes réelles sont souvent de faible intensité, distribuées et persistantes.

La surface d'attaque de l'authentification WordPress : wp-login.php et xmlrpc.php

wp-login.php est le principal point de connexion interactif. Il est ciblé à la fois pour les prises de contrôle de comptes et les pressions de type DoS.

xmlrpc.php existe pour les intégrations existantes et la publication à distance. S'il est laissé ouvert, il peut élargir les modes d'interaction des robots avec l'authentification et peut être utilisé comme un canal d'automatisation supplémentaire.

Si votre site n'a pas strictement besoin de XML-RPC, la suppression ou la limitation stricte de ce service est l'un des moyens les plus efficaces de réduire l'exposition au risque.

Simulation sûre et autorisée : que tester sans nuire à la production ?

Une simulation réaliste est définie par trois propriétés :

Limité : les tests sont assortis de plafonds de taux, de fenêtres temporelles et de conditions d'arrêt.

Mesurable : vous enregistrez les blocs de bord, la charge d'origine, les taux d'erreur, la latence et les événements d'authentification.

Représentant : Les scénarios modélisent à la fois les modèles "rapides/bruyants" et "lents/distribués".

L'objectif n'est pas de "s'introduire". L'objectif est de vérifier ces affirmations par des preuves :

- La plupart du trafic hostile est bloqué ou étranglé avant d'atteindre PHP.

- Les utilisateurs légitimes peuvent toujours se connecter pendant la pression.

- Les journaux contiennent suffisamment de données pour permettre d'enquêter et de réagir.

- Aucune erreur de configuration (plugin, point d'extrémité, contournement du WAF) n'entraîne l'effondrement de l'ensemble de la défense.

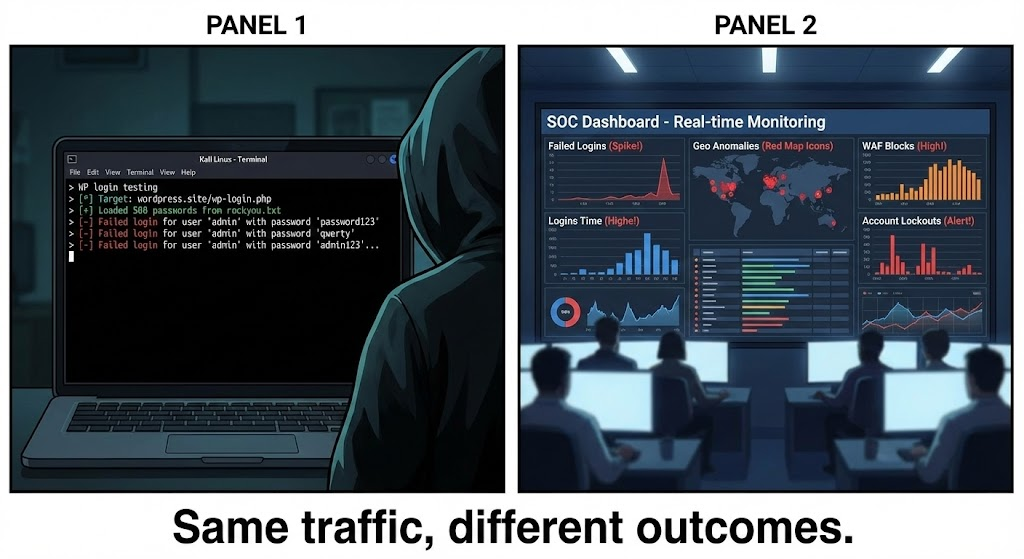

Kali Linux est couramment utilisé comme poste de travail de sécurité pour exécuter des processus de test autorisés, mais le système d'exploitation n'est pas la défense - c'est l'ingénierie et les mesures qui le sont.

Créer un environnement de test qui reflète le risque réel

Un test significatif nécessite une pile qui ressemble à la production :

- Même modèle d'hébergement (NGINX/Apache, comportement PHP-FPM, mise en cache)

- Même couche périphérique (CDN/WAF/règles pour les robots)

- Les mêmes plugins critiques et chemins d'accès aux thèmes qui affectent l'authentification

- Même configuration d'authentification (MFA, verrouillage, rôles d'utilisateur, routes d'administration)

Utilisation comptes de test uniquementavec des rôles réalistes :

- Administrateur Utilisateur test

- Editeur utilisateur test

- Abonné utilisateur test

Cela vous permet de valider à la fois les contrôles de sécurité et le rayon d'action.

L'instrumentation d'abord : la télémétrie qui rend les résultats fiables

Avant toute simulation, il faut s'assurer que ces sources de télémétrie existent :

Télémétrie Edge/CDN/WAF

- Demande de volume par chemin d'accès (

/wp-login.php,/xmlrpc.php) - Actions de blocage/de contestation et motifs

- Principaux IP/ASN et pays sources

- Score de Bot ou distribution de la réputation (si disponible)

Télémétrie d'origine

- Codes de réponse (200/302/403/429/5xx)

- Latence et queue de latence (p95/p99)

- Utilisation et saturation des travailleurs PHP

- Pression de connexion à la base de données (le cas échéant)

Télémétrie de l'application

- Échecs/réussites de connexion avec horodatage, nom d'utilisateur tenté, IP/IP transférée, agent utilisateur

- Événements de verrouillage et déclencheurs de défis

- Changements de rôle inattendus ou création d'un nouvel utilisateur administratif

Sans cette visibilité, les "tests de sécurité" deviennent de la narration plutôt que de l'ingénierie.

Un plan de test réaliste : des scénarios qui reflètent le comportement des attaquants

Un plan de validation solide est basé sur des scénarios et non sur des outils.

Scénario A : Santé de base

Enregistrez la latence de connexion normale et l'utilisation des ressources dans le cadre d'un comportement légitime. C'est votre point de référence.

Scénario B : vague de robots bruyante (stress de disponibilité)

Simuler un court épisode de trafic de connexion élevé. Critères de réussite :

- Les blocages/problèmes de bord augmentent fortement

- La charge d'origine reste stable

- Pas d'erreurs 5xx soutenues

- La connexion légitime reste possible

Scénario C : Pression distribuée faible et lente

Simuler des tentatives soutenues, à un rythme modeste et étalées dans le temps. Critères de réussite :

- Limitation du débit/engagements de retrait sans nuire aux utilisateurs réels

- Les journaux d'authentification montrent clairement le schéma

- Les alertes se déclenchent en cas d'échecs de connexion anormaux, et pas seulement en cas de "pics".

Scénario D : l'UX attaquée

Pendant la pression active, procéder à des ouvertures de session et à des réinitialisations de mot de passe légitimes. Critères de réussite :

- Les utilisateurs réels peuvent s'authentifier

- Les politiques de verrouillage ne créent pas d'auto-doS

- Les défis apparaissent de manière sélective (pour les bots), et non universelle

Ingénierie défensive : des contrôles en couches qui survivent aux attaques réelles

Une défense efficace de l'accès à WordPress est constituée de plusieurs couches. Chaque couche a une fonction différente, et vous devez mesurer chacune d'entre elles.

Couche 1 : Durcissement de l'identité (réduction des chances de réussite de toute tentative)

Authentification multifactorielle (AMF) pour tous les utilisateurs privilégiés est le contrôle le plus puissant contre la réutilisation des informations d'identification. Si un mot de passe est compromis, l'AMF empêche la majorité des tentatives de prise de contrôle par mot de passe uniquement de se transformer en incidents.

Contrôles d'identité supplémentaires :

- Réduire le nombre de comptes administrateurs

- Supprimer les comptes périmés

- Renforcer les mots de passe forts et uniques (politiques de gestion des mots de passe)

- Appliquer le principe du moindre privilège (les rédacteurs ne sont pas des administrateurs ; les administrateurs ne sont pas partout)

Couche 2 : Contrôle des applications (ralentissement des robots, réduction du retour d'information des attaquants)

La couche applicative doit réduire le débit automatisé tout en préservant la convivialité :

- Utiliser des erreurs de connexion cohérentes qui ne révèlent pas l'existence d'un nom d'utilisateur.

- Préférer le backoff progressif et les étranglements temporaires aux lockouts longs et durs

- Déclencher des challenges (CAPTCHA/bot challenges) de manière conditionnelle lorsque le trafic semble automatisé

- Gérer avec soin les flux de réinitialisation des mots de passe afin qu'ils ne puissent pas être utilisés de manière abusive à des fins d'énumération ou de spam.

Couche 3 : Réduction de la surface (xmlrpc.php et autres expositions inutiles)

Si XML-RPC n'est pas nécessaire, désactivez-le.

S'il est nécessaire, il faut l'ouvrir :

- N'autorisez que des sources fiables lorsque c'est possible

- Limite de taux agressive

- Contrôler le niveau de référence de la demande séparément de la

wp-login.php

La réduction de la surface n'est pas une "sécurité par l'obscurité". Il s'agit de supprimer les voies d'attaque inutiles.

Couche 4 : Contrôles de l'infrastructure (protection de PHP et de la base de données)

La couche la moins chère doit bloquer le plus de trafic.

- Gestion des CDN/WAF/bots pour bloquer ou défier l'automatisation à la périphérie.

- Limitation du débit du serveur web Origin pour éviter l'épuisement des travailleurs PHP

- Mise en cache et optimisation des connexions pour maintenir une disponibilité stable sous pression

Un mode d'échec courant consiste à laisser un trafic hostile atteindre PHP, puis à essayer de le "réparer" avec les seuls plugins WordPress. Cette solution est coûteuse et fragile à grande échelle.

Limitation du débit côté serveur : le filet de sécurité de la disponibilité

Même avec une protection à la périphérie, la limitation du débit d'origine est essentielle car elle empêche les scénarios de contournement de se transformer en temps d'arrêt.

Le bon objectif n'est pas de "tout bloquer", mais de.. :

- plafonner les taux de requêtes anormales vers les points d'entrée d'authentification

- protéger les pools de travail de PHP-FPM

- éviter de nuire aux utilisateurs légitimes

La limitation des bons taux a trois propriétés :

- Il est adapté à votre niveau de référence

- Elle comporte des règles distinctes pour

/wp-login.phpet/xmlrpc.php - Il est observable (vous pouvez voir quand et pourquoi il se déclenche)

Des signaux de détection plus performants que la signature seule

Une attaque par login est souvent visible sous forme de schémas, et non d'événements individuels.

Les indicateurs de haut niveau sont les suivants

- une augmentation durable du nombre d'échecs de connexion par rapport à la situation de départ

- tentatives réparties sur plusieurs comptes ayant des traits de comportement communs

- géographie anormale/écarts par rapport à l'heure du jour

- défis élevés pour les points de terminaison d'authentification

- Augmentation de la latence de la queue et saturation des travailleurs PHP lors de la pression d'authentification

Le blocage d'une seule adresse IP est rarement suffisant. La corrélation est la différence entre le bruit et l'intelligence.

Réponse aux incidents : que faire lorsque la pression devient un événement ?

Lorsque la pression d'authentification est détectée, la réponse doit être cohérente et rapide :

- Confirmer l'état de l'origine (latence, taux d'erreur, saturation des travailleurs).

- Renforcer les contrôles à la périphérie pour les points de terminaison d'authentification (augmenter les seuils de contestation, les limites de taux).

- Appliquer des règles d'origine plus strictes si nécessaire pour protéger PHP.

- En cas de suspicion de compromission :

- auditer les utilisateurs et les rôles des administrateurs

- rotation des informations d'identification et mise en œuvre de l'AMF

- revoir les changements de plugin/thème

- vérifier les connexions sortantes inattendues ou les modifications de fichiers

- Examen post-incident : mise à jour des seuils, des règles et des champs d'enregistrement sur la base d'éléments probants.

L'objectif n'est pas seulement de récupérer, mais aussi d'améliorer le système pour que le même modèle soit moins coûteux à gérer la prochaine fois.

Comment rendre compte des résultats en tant qu'ingénieur - la preuve plutôt que l'opinion

Un rapport utile comprend

- Scénarios exécutés et durée

- Forme du trafic (en rafale ou soutenu, à source unique ou distribué)

- Résultats : taux de blocage/de contestation, principaux points d'aboutissement ciblés, raisons.

- Résultats à l'origine : temps de latence (p95/p99), utilisation des travailleurs, taux d'erreur

- Résultats de l'application : échecs/réussites de l'authentification, comportement de verrouillage

- Résultats UX : les connexions légitimes sont-elles restées fluides ?

- Lacunes : où le trafic a atteint, qu'est-ce qui n'a pas été déclenché, qu'est-ce qui devrait être ajusté ?

Si la plupart du trafic hostile est arrêté avant PHP, que l'origine reste stable et que les utilisateurs légitimes peuvent se connecter, le système est résilient. Si la pression d'authentification peut saturer les travailleurs ou produire des erreurs 5xx, la disponibilité est menacée même si aucun compte n'a été compromis.

Conclusion

La défense de la connexion WordPress n'est pas un plugin ou une règle. Il s'agit d'un système à plusieurs niveaux conçu pour résister à l'automatisation, préserver la convivialité, protéger la disponibilité et fournir une visibilité claire en cas de pression.

Une simulation réaliste permet de vérifier si votre système résiste à l'économie réelle des attaquants : trafic distribué, tentatives lentes et faibles et sondages persistants. L'ingénierie défensive transforme ensuite ces résultats en contrôles concrets : MFA pour les utilisateurs privilégiés, étranglement et défis prudents, réduction de l'exposition de surface (en particulier XML-RPC lorsque cela n'est pas nécessaire), forte protection des bords, limitation du taux d'origine et télémétrie exploitable.

Lorsque ces couches fonctionnent ensemble, l'authentification WordPress devient beaucoup plus difficile à compromettre et beaucoup moins susceptible de devenir la source d'un temps d'arrêt.