CVE-2026-2441 is a high-severity use-after-free vulnerability (CWE-416) in Chrome’s CSS component. The NVD description is direct: Chrome prior to 145.0.7632.75 can be driven—via a crafted HTML page—into arbitrary code execution inside the sandbox. (NVD)

Google shipped fixes in the Desktop Stable channel update on February 13, 2026:

- Windows and macOS: 145.0.7632.75/76

- Linux: 144.0.7559.75 (Chrome Releases)

And the “drop what you’re doing” signal is not subtle: NVD indicates the CVE is in CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog, with Date Added 02/17/2026 et Due Date 03/10/2026. (NVD)

This is the operational reality: you are racing a timeline that already started without you.

What is confirmed and what is intentionally not disclosed

The most important thing to internalize about exploited browser issues is that the best public sources will often withhold exploitation specifics early on, on purpose. Google’s release communications commonly keep bug details restricted until a majority of users are patched—this pattern shows up right in the Chrome Releases blog index for February 2026. (Chrome Releases)

So what est safe to treat as fact?

- The vulnerability class: use-after-free in CSS (NVD)

- The impact as described in canonical records: arbitrary code execution inside the sandbox via crafted HTML (NVD)

- The fixed version floors for Stable Desktop on Feb 13, 2026 (Chrome Releases)

- The exploited status signaled by CISA KEV inclusion, including a remediation due date (NVD)

- The release-note credit: Chrome release notes list the issue and credit the reporter (not always necessary for operations, but relevant for timeline integrity). (Chrome Releases)

What you should not build your response around:

- Precise exploit chains, payload behavior, or actor TTP claims that aren’t in vendor or government canonical sources. Public reporting can be helpful for urgency framing, but it’s not a substitute for your own telemetry.

The minimum safe versions you can actually enforce

For this incident, “patched” is not a vibe. It’s a version number.

Stable channel fixed floors

Google’s Stable Channel Update for Desktop on Feb 13, 2026 states:

- 145.0.7632.75/76 for Windows and Mac

- 144.0.7559.75 for Linux (Chrome Releases)

Extended Stable fixed floor

If your org runs Extended Stable for fleet stability, don’t accidentally enforce the wrong floor. The Chrome Releases February index shows Extended Stable updates and explicitly lists an Extended Stable build that includes CVE-2026-2441 with version 144.0.7559.177 for Windows and Mac on Feb 13, 2026. (Chrome Releases)

Here’s the compliance table you can paste into an internal runbook:

| Chaîne | OS | Vulnerable if below | Safe floor to enforce | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable | Fenêtres | 145.0.7632.75 | 145.0.7632.75 or newer | Chrome Releases (Chrome Releases) |

| Stable | macOS | 145.0.7632.75 | 145.0.7632.75/76 or newer | Chrome Releases (Chrome Releases) |

| Stable | Linux | 144.0.7559.75 | 144.0.7559.75 or newer | Chrome Releases (Chrome Releases) |

| Extended Stable | Fenêtres | 144.0.7559.177 | 144.0.7559.177 or newer | Chrome Releases (Chrome Releases) |

| Extended Stable | macOS | 144.0.7559.177 | 144.0.7559.177 or newer | Chrome Releases (Chrome Releases) |

If you only do one thing today, do this: build your enforcement and reporting around the correct channel floor. Many fleets have a “Stable by policy” assumption that stops being true the moment a subset of endpoints is pinned to Extended Stable.

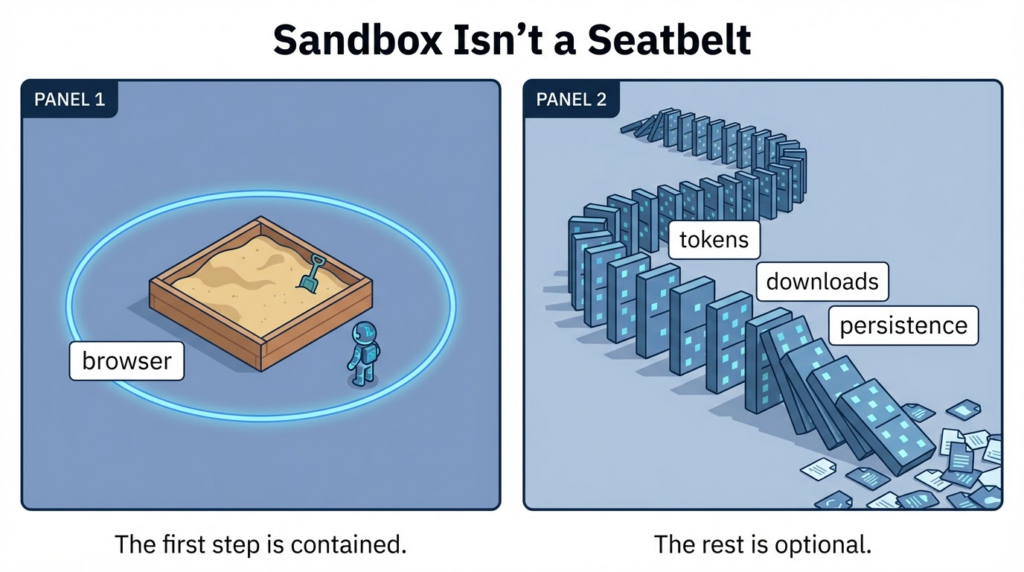

Why sandboxed code execution is still treated as emergency-class risk

NVD’s wording includes “execute arbitrary code inside a sandbox.” (NVD)

That phrase tempts teams to deprioritize: “It’s sandboxed, so we’re fine.”

That’s not how browser incidents behave in the real world.

A browser sandbox is an engineering boundary, not a business boundary. A sandboxed foothold still sits at a high-value intersection of:

- authenticated sessions

- browser-stored credentials or tokens

- access to internal web apps

- user trust pathways for downloads and click-through flows

And adversaries don’t need your sandbox to be perfect. They need it to be good enough to stage the next step: social engineering the user into authorizing something, abusing a permitted helper process, or chaining into another weakness.

This is why exploited browser CVEs get emergency comms that sound repetitive: “Update now.” Tech reporting amplifies it because it maps to the only action that reliably breaks broad exploitation. (TechRadar)

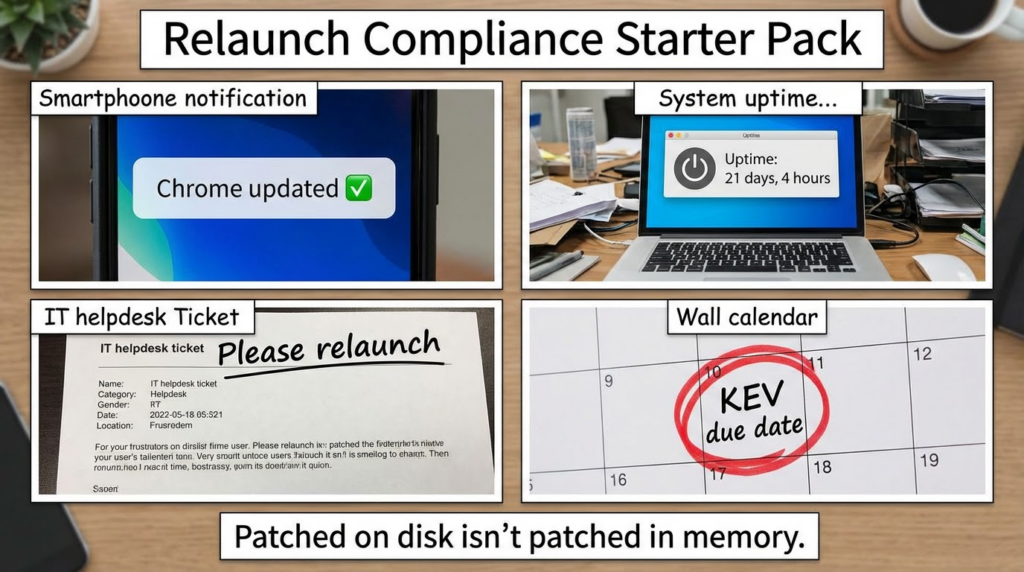

The real failure mode in most orgs is not patching, it is verification

The most common postmortem line in client-side incidents is basically:

“We pushed the update. We assumed that meant it was deployed.”

For Chrome specifically, there are three separate realities you must reconcile:

- Binaries on disk are updated

- The browser process is still running the old version until relaunch

- Your reporting might read “updated” even when the old process is still the one users are browsing with

So you want an evidence chain that answers:

- Which endpoints have Chrome installed

- Which channel they’re actually on

- Which version is installed

- Which version is running

- Whether a relaunch happened after patch availability

This is why “restart your browser” is emphasized in public advisories and practical coverage; it’s not fluff, it’s control reality. (TechRadar)

The fastest way to verify exposure on one machine

These checks are purely defensive. They do not interact with any exploit behavior.

macOS version check

/Applications/Google\\ Chrome.app/Contents/MacOS/Google\\ Chrome --version 2>/dev/null \\

|| mdls -name kMDItemVersion /Applications/Google\\ Chrome.app 2>/dev/null

Linux version check

google-chrome --version 2>/dev/null || google-chrome-stable --version 2>/dev/null \\

|| chromium --version 2>/dev/null

Windows PowerShell version check

$chrome = "${env:ProgramFiles}\\Google\\Chrome\\Application\\chrome.exe"

if (Test-Path $chrome) {

(Get-Item $chrome).VersionInfo.ProductVersion

} else {

"Chrome not found at default path"

}

Compare your output to the fixed floors from Google’s Feb 13 Desktop update. (Chrome Releases)

Fleet-scale verification that holds up in an audit

If you want to be able to say “we remediated CVE-2026-2441” with a straight face, you need something stronger than screenshots.

A defensible minimum standard is:

- a timestamped inventory export of Chrome versions by endpoint

- a policy or management report showing update enforcement

- a restart/relaunch compliance signal (where available)

- a gap list and a remediation plan for exceptions

A practical control statement

A good internal control statement sounds like this:

As of 2026-02-XX, 99.7% of endpoints are running Chrome at or above the fixed version floors for their channel. Remaining exceptions are isolated and scheduled for remediation. CISA KEV due date is 2026-03-10. (NVD)

That last line matters because it anchors your urgency to a government exploitation tracking mechanism rather than a vibes-based priority label.

Response playbook that doesn’t assume you are lucky

This section is intentionally structured like something you can run during an incident bridge.

Phase 1 Immediate actions within hours

1. Push or approve the fixed versions

Stable Desktop fixed builds are explicitly listed by Google. (Chrome Releases)

Extended Stable fixed builds are listed in the Chrome Releases February index. (Chrome Releases)

2. Enforce a relaunch window

If you do not have a relaunch compliance mechanism, treat that as a gap and compensate with communications plus targeted checks on high-risk populations.

3. Identify exposure scope

Build a list of endpoints that were below the fixed floor during the exposure window. That list becomes your hunt priority.

4. Record evidence early

You will forget later. Capture the versions you found, when you found them, and which management control pushed the update.

Phase 2 Short-term actions within 24 to 72 hours

1. Hunt for post-exploitation patterns rather than exploit signatures

When vendors intentionally restrict details, signature hunting is fragile. Behavioral hunting is resilient.

2. Prioritize high-risk user groups

Admins, engineers with privileged browser sessions, finance, and anyone with access to crown-jewel SaaS apps.

3. Correlate suspicious activity with patch lag

The endpoints that delayed relaunch are the ones worth deeper review.

Phase 3 Medium-term hardening within a week

1. Reduce “click-to-execution” pathways temporarily

You’re not trying to lock down the internet forever. You’re trying to reduce blast radius while patch adoption hits a safe threshold.

2. Fix the structural gap

If you cannot reliably assert “running version,” you do not actually have a browser patch control, you have a browser patch hope.

Hunting guidance you can deploy without relying on exploit internals

NVD indicates the CVE’s CVSS v3.1 vector includes UI:R, meaning user interaction is part of the model. (NVD)

In practice, that usually means: user visits a page, clicks something, or the page triggers behavior through normal browsing flows.

So you hunt the parts you can observe:

- Chrome spawning unusual child processes

- suspicious downloads followed by execution

- new persistence entries shortly after browsing sessions

- outbound connections to unusual infrastructure soon after Chrome activity

Microsoft Sentinel KQL example

// Chrome spawning unusual child processes

DeviceProcessEvents

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "chrome.exe"

| where FileName !in~ ("chrome.exe", "crashpad_handler.exe")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName, InitiatingProcessFileName, FileName, ProcessCommandLine

| order by Timestamp desc

Splunk SPL example

index=endpoint (parent_process_name="chrome.exe" OR process_parent="*chrome*")

| stats count values(process_name) values(command_line) by host user

| sort - count

These queries don’t claim “this detects CVE-2026-2441.” They are designed to catch what you actually investigate when an exploited browser issue is in play: second-stage behavior.

The communication template your SOC and IT will both tolerate

Here’s a tone that reads like a competent human, not a compliance robot:

- We are addressing an actively exploited Chrome vulnerability tracked as CVE-2026-2441. (NVD)

- Google released fixed versions on Feb 13, 2026 for both Stable and Extended Stable channels. (Chrome Releases)

- Users must relaunch Chrome to complete the remediation.

- IT will enforce the update. Security will verify running versions and hunt for suspicious post-browse behavior on endpoints that lagged behind.

That’s enough to keep people focused without over-claiming.

How CVE-2026-2441 shows up in KEV-driven prioritization

KEV inclusion changes the conversation. It’s a public, government-backed statement that exploitation is happening and remediation is time-bound.

On the NVD page, the KEV section explicitly lists:

- Vulnerability Name: Google Chromium CSS Use-After-Free Vulnerability

- Date Added: 02/17/2026

- Due Date: 03/10/2026

- Required Action language referencing vendor mitigations (NVD)

Even if you’re not required to follow BOD 22-01, KEV is still a solid reason to move this ahead of routine backlog work.

Related vulnerabilities you should consider in your browser risk narrative

When you’re writing for engineers, it helps to contextualize CVE-2026-2441 as part of a broader class of issues, without turning the article into a CVE keyword dump.

The correct framing is:

- Browser exploitation remains attractive because user interaction is abundant and patch gaps are inevitable

- Memory safety issues like use-after-free are a recurring theme

- The remediation discipline that works here is the same discipline that works for other exploited client-side CVEs: version floors, relaunch compliance, telemetry-backed hunting, and evidence collection

If you want to add adjacent CVEs in a follow-up expansion, prioritize those that are either in KEV or have confirmed in-the-wild exploitation. Keep it evidence-based. Don’t overfit to speculative chains.

If your organization is trying to turn patching into a measurable, evidence-first workflow, this is exactly the kind of incident where “automation” is not about running more tools—it’s about closing the loop:

- convert version requirements into enforceable checks

- collect proof artifacts that hold up in audits

- generate a repeatable remediation report for security leadership

If you’re already building those runbooks, an AI-driven penetration testing and verification platform can help operationalize them into tasks with standardized outputs and faster iteration.

Relevant Penligent background pages tied to this CVE topic are already published as part of your hacking labs stream, and can serve as internal linking targets for readers who want a tool-oriented workflow narrative. (Penligent)

FAQ that matches what people actually ask

Is this really exploited or just “theoretical”

CISA KEV inclusion signals evidence of active exploitation, and NVD reflects that status along with the KEV dates and due date. (NVD)

What versions do we need to be on

For Stable Desktop, Google states fixed versions 145.0.7632.75/76 for Windows/Mac and 144.0.7559.75 for Linux. (Chrome Releases)

For Extended Stable, Chrome Releases lists 144.0.7559.177 for Windows and Mac in February 2026 updates that include CVE-2026-2441. (Chrome Releases)

If auto-update is on, are we safe

Only after a relaunch. Your best practice is to measure running versions, not just installed packages. Public guidance consistently emphasizes “restart/relaunch” for a reason. (TechRadar)

Should we assume compromise

Assume exposure until you can prove version floors plus relaunch compliance. Then prioritize hunts on endpoints that lagged behind, because that is where risk concentrates.

Références

- NVD CVE-2026-2441: https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-2441 (NVD)

- CVE.org record: https://www.cve.org/CVERecord?id=CVE-2026-2441 (CVE)

- Chrome Releases Stable Channel Update for Desktop Feb 13, 2026: https://chromereleases.googleblog.com/2026/02/stable-channel-update-for-desktop_13.html (Chrome Releases)

- Chrome Releases February 2026 index showing Extended Stable entry and the CVE line item: https://chromereleases.googleblog.com/2026/02/ (Chrome Releases)

- TechRadar coverage summarizing the urgency and fixed versions: https://www.techradar.com/pro/security/google-patches-first-chrome-zero-day-of-the-year-so-update-now-or-face-attack (TechRadar)

- Malwarebytes coverage calling out the “update now” operational messaging: https://www.malwarebytes.com/blog/news/2026/02/update-chrome-now-zero-day-bug-allows-code-execution-via-malicious-webpages (Malwarebytes)

- https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-2441-the-chrome-css-zero-day-that-starts-inside-the-sandbox-and-rarely-ends-there/ (Penligent)

- https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-2441-the-chrome-css-zero-day-that-demands-proof-not-promises/ (Penligent)

- https://penligent.ai/ (Penligent)