Les mots de passe Safari désignent les informations d'identification que le navigateur Safari d'Apple stocke localement ou dans le trousseau iCloud. Pour les ingénieurs en sécurité, il est essentiel de comprendre comment ces mots de passe sont gérés, protégés et parfois exposés lors d'attaques réelles afin de créer des applications sécurisées et d'évaluer les risques de vol d'informations d'identification.

Safari intègre le stockage des mots de passe et le remplissage automatique en profondeur avec les plateformes Apple et iCloud Keychain, ce qui permet une réutilisation pratique des identifiants sur tous les appareils, mais introduit également des considérations complexes en matière de sécurité. Dans ce guide, nous analyserons non seulement les mécanismes de gestion des mots de passe, mais aussi les vulnérabilités documentées, les modèles de menace et les pratiques défensives renforcées.

Ce que signifie l'expression "Safari Passwords" (mots de passe Safari)

Le système de mot de passe de Safari comporte plusieurs éléments :

- Stockage local des informations d'identification dans le trousseau du système d'exploitation

- Synchronisation du trousseau iCloud sur l'ensemble des appareils

- AutoFill fonctionnalité dans le navigateur et les applications

- Gestion des mots de passe par l'utilisateur via les paramètres du système

Le stockage sous-jacent est chiffré et, lorsqu'il est synchronisé via iCloud, il est chiffré de bout en bout à l'aide des clés de l'appareil. La conception d'Apple empêche intentionnellement même les serveurs Apple de décrypter les mots de passe des utilisateurs en transit ou au repos. Cependant, la logique de remplissage automatique et les couches de l'interface utilisateur ont toujours été des zones d'attaque.Ces derniers interagissent avec les pages web et les données saisies par les utilisateurs, deux domaines qui recèlent un potentiel d'adversité. (support.apple.com)

Vulnérabilités historiques dans la gestion des mots de passe de Safari

Plusieurs CVE montrent comment les composants de Safari relatifs aux mots de passe et au remplissage automatique ont été exploités ou pourraient l'être lorsque les mesures de protection sont insuffisantes :

CVE-2018-4137 : Exposition au remplissage automatique de Safari

CVE-2018-4137 est une vulnérabilité documentée dans iOS et Safari d'Apple, dans laquelle la fonction La fonctionnalité Login AutoFill manque de confirmation explicite de la part de l'utilisateur avant de remplir les informations d'identification enregistrées. Cette faille permettait à un site web conçu de lire les données de nom d'utilisateur et de mot de passe remplies automatiquement sans le consentement direct de l'utilisateur. Le composant vulnérable était "Safari Login AutoFill", et Apple a publié des mises à jour pour remédier au problème. yisu.com

Il s'agit d'une catégorie de vulnérabilité dans laquelle les informations d'identification sont révélées par des failles logiques plutôt que par des faiblesses cryptographiques. Il souligne que la "couche UX de remplissage automatique" est techniquement une interface puissante entre les secrets stockés et le contenu distant.

Autres questions connexes

- Vulnérabilités liées à l'usurpation de logique et d'interface utilisateur pourrait inciter Safari à afficher des URL ou des boîtes de dialogue incorrectes, ce qui pourrait influencer le comportement de remplissage automatique. soutien de la pomme

- Des erreurs historiques de remplissage automatique et des bogues de logique API ont existé à la fois dans des extensions de navigateur et des gestionnaires de mots de passe intégrés, illustrant le fait que le traitement des informations d'identification dépend fortement de l'intégrité de l'interface utilisateur et de la logique du back-end. soutien de la pomme

Bien que la plupart de ces problèmes plus anciens aient été corrigés, ils illustrent de manière instructive les points suivants pourquoi les ingénieurs en sécurité doivent examiner les mécanismes de remplissage automatique comme n'importe quelle surface d'API d'informations d'identification.

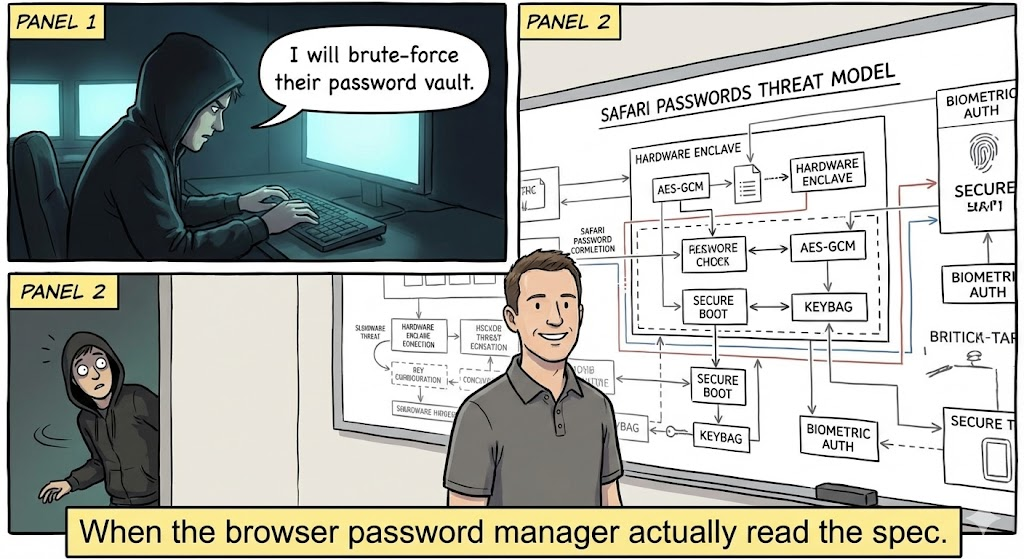

Modèles de menace pour les mots de passe Safari

Les principales catégories de risques pour mots de passe safari inclure :

| Modèle de menace | Description | Exemple d'impact |

|---|---|---|

| Fuite de données d'identification à distance | Un attaquant trompe la logique de remplissage automatique | Mot de passe exposé à un script malveillant |

| Usurpation d'interface utilisateur | De faux formulaires de connexion capturent les informations d'identification | Vol d'identité |

| Abus de prolongation | Une extension malveillante ou compromise extrait des données | Exfiltration de mot de passe |

| Compromis local | Logiciels malveillants ou accès physique à l'appareil | Extraction du trousseau |

| Détournement de réseau | L'homme du milieu force la soumission d'informations d'identification sur HTTP | Risque lié aux formulaires non sécurisés |

Ce tableau permet de présenter les menaces non seulement comme des "bogues de navigateur", mais aussi comme des "bogues d'ordinateur". risques liés au système et à l'interface qui nécessitent des défenses à plusieurs niveaux.

Comment Safari stocke et protège les mots de passe

La sécurité des mots de passe de Safari repose sur les éléments suivants :

- Cryptage du trousseau - Les mots de passe locaux sont stockés en toute sécurité à l'aide des API cryptographiques de la plateforme.

- Synchronisation de bout en bout avec iCloud - Lorsque cette option est activée, les informations d'identification sont synchronisées entre les appareils de confiance à l'aide de clés de chiffrement spécifiques à l'appareil.

- Portes d'authentification de l'utilisateur - L'accès aux détails du mot de passe nécessite généralement Face ID / Touch ID / code d'accès.

- Politiques de remplissage automatique sécurisées - En général, Safari ne remplit automatiquement les formulaires qu'avec HTTPS et demande à l'utilisateur d'agir.

Toutefois, les fonctions de commodité élargissent souvent les interfaces entre le contenu des pages non fiables et la logique d'accès aux informations d'identification.

Exemples de codes d'attaque et de défense

Pour illustrer l'exposition des titres de compétences et les meilleures pratiques défensives, voici quelques exemples. 5 exemples concrets concernant le remplissage automatique du mot de passe et la gestion des formulaires dans Safari.

Exemple 1 : Détection de formulaires de connexion HTTP non sécurisés (surface d'attaque)

javascript

document.querySelector("form").addEventListener("submit", function (e) {

if (location.protocol !== "https :") {

console.error("Blocking insecure password submission") ;

e.preventDefault() ;

}

});

Cela bloque les soumissions de formulaires par HTTP, qui pourraient autrement permettre des fuites ou des attaques par dégradation.

Exemple 2 : Empêcher le remplissage automatique des champs sensibles

html

<input type="password" autocomplete="new-password" />

Les autocomplete="nouveau-mot-de-passe" signale que l'attribut Les navigateurs ne doivent pas remplir automatiquement les informations d'identification stockées.

Exemple 3 : Le CSP pour restreindre l'exposition des données d'identification

html

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'self'; form-action 'self';">

Un strict Politique de sécurité du contenu permet d'éviter le vol d'informations d'identification par le biais de formulaires malveillants.

Exemple 4 : Durcissement de la logique de l'interface utilisateur pour confirmer l'autorisation du remplissage automatique

javascript

async function requestAutofill() {

if (await authenticateUser()) {

const creds = await browser.passwords.get({ url : location.origin }) ;

fillForm(creds) ;

}

}

Ce modèle impose une confirmation explicite de l'utilisateur avant toute opération risquée de remplissage automatique.

Exemple 5 : Stockage sécurisé des mots de passe via des API natives (iOS/Swift)

rapide

let query : [String : Any] = [

kSecClass as String : kSecClassGenericPassword,

kSecAttrAccount as String : "exempleCompte",

kSecValueData as String : passwordData

]

SecItemAdd(query as CFDictionary, nil)

L'utilisation API du trousseau de clés de la plate-forme garantit l'application des protections natives (touch/face ID gating).

Meilleures pratiques pour protéger les mots de passe Safari

Contrôles de sécurité mots de passe safari devrait inclure :

- Appliquer le protocole HTTPS pour toutes les soumissions de formulaires

- Utiliser des restrictions strictes en matière de CSP et de form-action

- Valider et assainir la logique de déclenchement du remplissage automatique du mot de passe

- Contrôler et limiter les autorisations d'extension

- Vérifier l'accès au trousseau iCloud avec l'authentification de l'appareil

Ces pratiques concernent à la fois Logique de l'interface utilisateur et sécurité de la filière des titres.

Penligent : Détection de l'exposition des données d'identification pilotée par l'IA

Dans les applications web complexes, les tests automatisés passent souvent à côté de problèmes subtils liés au chemin d'accès aux informations d'identification, en particulier ceux qui impliquent un remplissage automatique ou une logique de formulaire basée sur des scripts. Des plateformes comme Penligent aider les équipes d'ingénieurs en :

- Identifier les déclencheurs de remplissage automatique à risque en JavaScript front-end

- Corrélation entre les champs de formulaire, les API d'identification et les modèles de stockage

- Détection des comportements de remplissage automatique non autorisés dans les pages dynamiques

- Intégration dans CI/CD pour détecter les problèmes à un stade précoce

Plutôt que d'analyser les pages de manière statique, l'IA de Penligent analyse la manière dont les scripts interagissent avec les API de formulaires et d'informations d'identification au moment de l'exécution, en découvrant les failles logiques susceptibles d'exposer les mots de passe, même si les couches du navigateur et du système d'exploitation sont techniquement sécurisées.

Les CVE connexes méritent d'être examinés

La référence à des CVE antérieurs permet d'illustrer comment le remplissage automatique et la logique des mots de passe ont constitué une surface d'attaque significative :

- CVE-2018-4137: Safari Login AutoFill ne demandait pas de confirmation explicite et pouvait exposer les informations d'identification à des contenus élaborés. yisu.com

- CVE-2018-4134: Usurpation de l'interface utilisateur de Safari entraînant un domaine ou un contexte d'authentification incorrect. cve.mitre.org

- CVE-2024-23222 & d'autres CVE ayant un impact sur WebKit démontrent comment les failles du moteur de navigation influencent la sécurité de manière générale. cve.mitre.org

La compréhension de ces éléments montre que la sécurité des mots de passe ne concerne pas seulement le stockage, mais aussi la manière dont les navigateurs interagissent avec des contenus non fiables.

Conclusion

mots de passe safari se situent à l'intersection de la commodité et de la sécurité. Si le trousseau iCloud et l'AutoFill sont faciles à utiliser, ils élargissent la surface d'attaque à l'intérieur du système. les couches de logique client et d'interaction avec le navigateur. Les CVE historiques montrent que les défauts de logique et d'interface utilisateur - et pas seulement les faiblesses cryptographiques - entraînent un risque réel. En combinant des politiques strictes en matière de forme et de CSP, des modèles de programmation défensifs et des tests automatisés (par exemple, des plateformes alimentées par l'IA comme Penligent), les équipes d'ingénieurs peuvent sécuriser de manière plus fiable les flux de travail relatifs aux informations d'identification, même dans des environnements web complexes.