What Security Engineers Actually Need It For and How to Use It Without Confusing PoCs With Proof

What Exploit DB Means in Real Security Work

When people search for exploit db, they are rarely asking a beginner question. Most are trying to answer a practical one under time pressure:

- Is there public exploit material for this vulnerability

- Does that material apply to my version or deployment

- Should this change patch priority

- Can I turn this into a controlled validation task instead of an argument about severity

That is why Exploit-DB still matters. OffSec describes The Exploit Database as a CVE-compliant archive of public exploits and corresponding vulnerable software, and explicitly notes that it is a repository for exploits and proof-of-concepts rather than advisories. (exploit-db.com)

That wording is the key to using it correctly.

Exploit-DB is not your final source of truth for risk. It is one of the fastest ways to move from a vulnerability identifier to a testable hypothesis.

What Exploit-DB Is and What It Is Not

Exploit-DB is maintained by OffSec as a public, non-profit service and is designed for penetration testers and vulnerability researchers. OffSec also states that the database is built from direct submissions, mailing lists, and other public sources, with the goal of making exploit material easy to navigate. (exploit-db.com)

That gives it a clear role in a modern workflow.

What Exploit-DB is good at

It is good at helping you quickly determine whether public exploit or PoC material exists, what product and version the material claims to target, and what kind of validation path might be possible in a lab or authorized environment. It is also useful when you need searchable local data for automation or restricted environments.

What Exploit-DB is not built to do

It is not a replacement for vendor advisories, not a substitute for NVD analysis, not a complete exploit intelligence feed, and not proof that your environment is exploitable. Its own positioning as a repository of exploits and PoCs rather than advisories is exactly why it is valuable and why it has limits. (exploit-db.com)

If you treat it as a conclusion engine, you will make bad decisions. If you treat it as an evidence source inside a larger pipeline, it becomes very powerful.

Why the Real Search Intent Behind Exploit DB Usually Becomes SearchSploit

There is no public source that reveals the true Google click-through rate for the keyword exploit db across the whole web. That data usually lives in private Search Console or commercial SEO tool accounts. The best public method is to analyze repeated search-result patterns and official ecosystem documentation.

In practice, one intent shows up again and again: SearchSploit.

Exploit-DB has an official SearchSploit manual page and a PDF manual. The manual page documents installation, updates, and usage. It states that on the standard GNOME build of Kali, the exploitdb package is already included by default, and shows the manual install path for Kali Light or custom builds. It also documents macOS installation via Homebrew and notes that Windows support is not straightforward, recommending alternatives like Kali VM, Docker, or WSL. (exploit-db.com)

Kali’s official tool documentation also shows SearchSploit usage examples and explicitly describes exploitdb as a searchable Exploit Database archive. It includes example commands and even shows JSON output usage such as searchsploit -j ... | jq. (Kali Linux)

This matters because it reveals the real user need behind the keyword. Many practitioners are not just browsing a website. They want:

- local searchable exploit corpus access

- repeatable CLI triage

- offline workflows

- scripting support

- consistent analyst behavior across teams

If your content on exploit db does not cover SearchSploit and validation workflows, it misses the main operational intent.

Exploit DB in a Modern Vulnerability Workflow

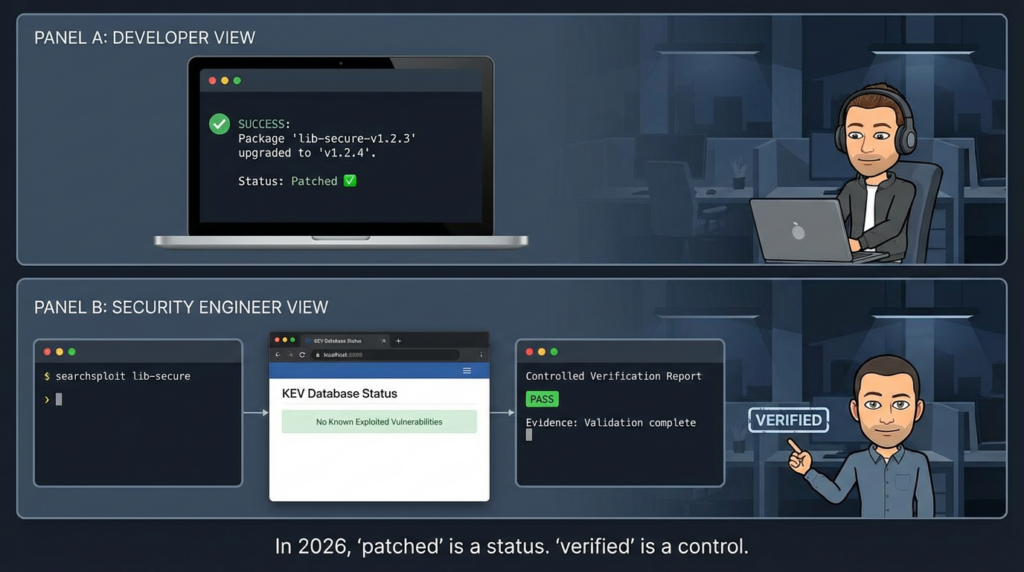

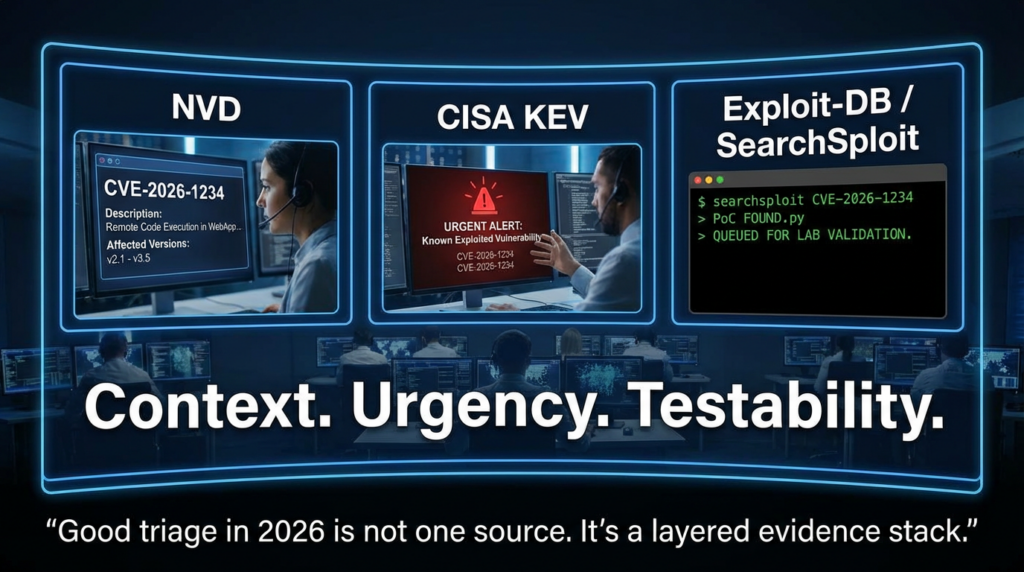

A clean vulnerability workflow separates signal, context, और proof.

Exploit-DB sits in the signal-and-context layer. It helps answer whether public exploit material exists and what assumptions it makes. It does not by itself prove exposure or impact in your environment.

A better workflow looks like this:

Start with CVE and vendor facts

Use CVE and NVD to understand the vulnerability description, affected components, and references. NVD’s API documentation also supports filtering by CISA KEV inclusion through the hasKev parameter and KEV date filters, which is useful for prioritization workflows. (एनवीडी)

Check whether active exploitation is known

CISA’s KEV catalog is the authoritative U.S. government source for vulnerabilities known to be exploited in the wild, and CISA explicitly recommends using the catalog as an input to vulnerability management prioritization. (सीआईएसए)

Use Exploit-DB to accelerate validation planning

If there is a public exploit or PoC, use it to understand:

- claimed versions

- preconditions

- protocol or endpoint assumptions

- platform-specific constraints

- likely detection points

- how to design a safe validation check

Produce evidence in your own environment

The final answer should come from your own evidence:

- asset and version verification

- exposure path confirmation

- controlled behavior testing

- pre-fix and post-fix comparison

- documented results

That is how you avoid two common failure modes: over-prioritizing a PoC that does not apply, and under-prioritizing a KEV issue just because no convenient Exploit-DB entry is available yet.

SearchSploit Practical Usage for Defensive Triage

SearchSploit is where Exploit-DB becomes operational for many teams.

The official manual documents install and update patterns, including searchsploit -u for updates, and notes that update frequency differs by installation method. (exploit-db.com)

Below are practical examples for searching and triaging. These are intentionally focused on safe use, not weaponization.

Installation examples

# Kali Linux

sudo apt update && sudo apt -y install exploitdb

# macOS with Homebrew

brew update && brew install exploitdb

These installation paths are documented by the official SearchSploit manual page. (exploit-db.com)

Basic searches

# Search by multiple keywords

searchsploit oracle windows remote

# Search by CVE identifier

searchsploit --cve 2021-44228

# Search by product name

searchsploit nginx

Kali’s official exploitdb tool page shows multiple example query patterns, including keyword combinations and CVE-based usage. (Kali Linux)

Useful analyst actions

# Update your local copy metadata

searchsploit -u

# JSON output for automation pipelines

searchsploit -j 55555 | jq

# Display help and usage examples

searchsploit -h

Kali’s docs show -j usage with jq, and the SearchSploit tooling examples list common search patterns. (Kali Linux)

A Safe Triage Pattern for Public PoCs

A strong exploit-db workflow is not “download and run.” It is “search, inspect, infer, validate safely.”

Here is a simple pattern that works well in security engineering teams:

First read the entry as metadata

Look for:

- product name

- version range

- platform

- exploit type

- CVE mapping

- test environment notes

- date of publication

- whether the entry is marked verified on the platform

For example, the Exploit-DB entry for DocsGPT 0.12.0 Remote Code Execution shows EDB-ID 52145, maps to CVE-2025-0868, lists the type as webapps, the platform as Python, and includes a version range in the code header. (exploit-db.com)

Then compare against primary disclosure sources

CERT Polska’s disclosure for CVE-2025-0868 states that the issue in DocsGPT could result in RCE due to improper parsing of JSON data using मूल्यांकन() in the /api/remote endpoint, and says it affects versions 0.8.1 through 0.12.0. (CERT Polska)

That aligns with the Exploit-DB listing and provides stronger confidence that you are not relying on a random reposted script title. This is the right workflow: use Exploit-DB for discoverability, but validate assumptions against primary sources.

Finally convert it into an internal validation task

A good validation task asks:

- Do we run this product

- Which versions do we run

- Is the relevant endpoint exposed

- Is auth required

- Can we verify reachability and patch state without destructive behavior

- What logs and telemetry should be checked

That is far more useful than a generic “critical CVE ticket.”

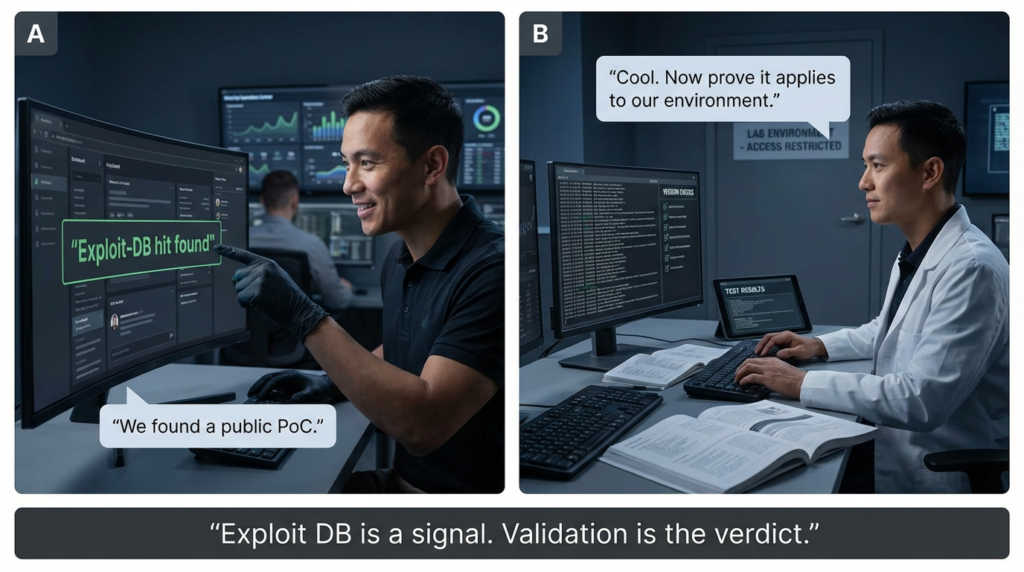

Why Public Exploit Availability Is Important but Not Final Proof

This is where many teams get into trouble.

A public PoC in Exploit-DB is a useful signal. It often means:

- the vulnerability has crossed from theoretical to reproducible in at least one environment

- technical details are now easier for both defenders and attackers to operationalize

- triage urgency may increase, especially for exposed services

But public PoC availability does not automatically mean your environment is exploitable.

PoCs often fail outside the author’s test conditions because of version drift, platform differences, patch backports, feature flags, auth requirements, segmentation, WAF behavior, reverse proxies, or simply brittle exploit code.

The opposite mistake is also common. Some organizations deprioritize vulnerabilities that have no Exploit-DB entry. That is a problem because active exploitation can happen before convenient public PoCs appear. That is exactly why KEV and vendor advisories need to be part of your process. NVD’s KEV-linked query support reflects this reality at the API layer. (एनवीडी)

A Better Evidence Model for Vulnerability Operations

The table below shows how Exploit-DB fits into an evidence-driven workflow.

| Evidence Source | What it tells you | Strength for prioritization | Strength for proving your exposure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset inventory and version detection | You likely run the affected software | High | मध्यम |

| Vendor advisory | Official affected and fixed versions | Very High | मध्यम |

| NVD record | Standardized CVE context and references | High | मध्यम |

| CISA KEV | Known exploitation in the wild | Very High | Low |

| Exploit-DB and SearchSploit | Public exploit or PoC material exists | High | Low to Medium |

| Controlled internal validation | Reproducibility in your environment | Very High | Very High |

| Post-fix regression test | Whether the tested path is no longer vulnerable | Very High | Very High |

This is the core discipline that makes exploit db useful without letting it drive bad risk decisions.

Recent CVE Examples That Show How Exploit DB Should Be Used

The goal here is not to publish exploit steps. It is to show how to combine public exploit repositories with authoritative references and internal testing.

CVE-2026-2441 and Browser Patch Urgency

Google’s Chrome stable desktop update on February 13, 2026 states that the Stable channel was updated to 145.0.7632.75/76 for Windows and Mac and 144.0.7559.75 for Linux. (Chrome Releases)

NVD’s CVE record for CVE-2026-2441 describes it as a use-after-free in CSS in Google Chrome prior to 145.0.7632.75, allowing a remote attacker to execute arbitrary code inside a sandbox via a crafted HTML page, and lists CWE-416. (एनवीडी)

CISA’s KEV catalog search snippets show CVE-2026-2441 listed in KEV, which materially changes prioritization urgency for organizations. (सीआईएसए)

How Exploit-DB fits here:

Exploit-DB is not your first source for browser zero-day patch facts. Vendor release notes and NVD are. But Exploit-DB and SearchSploit can become useful when public exploit references emerge and your team needs to understand assumptions, detection opportunities, or low-risk lab validation approaches.

For browser issues, the fastest operational value usually comes from:

- endpoint version inventory

- forced restart and update compliance checks

- web filtering and isolation controls

- detection for exploit-delivery attempts

That is a good example of using exploit-db as supporting evidence rather than the center of the workflow.

CVE-2025-0868 and Clear PoC-Driven Validation Planning

CVE-2025-0868 is a cleaner example of where Exploit-DB directly accelerates defender work.

CERT Polska documents the issue in DocsGPT and describes the root cause and affected version range. (CERT Polska)

NVD also has a public record for the CVE and shows that NVD enrichment state and NVD-assigned CVSS may not always be available immediately, while CNA-contributed data can already exist. (एनवीडी)

Exploit-DB hosts an entry that maps this issue to EDB-ID 52145 and CVE-2025-0868. (exploit-db.com)

This is exactly the kind of case where a security team can move quickly and responsibly:

- confirm public exploit material exists

- compare the PoC metadata with CERT disclosure

- identify whether the relevant endpoint exists in your deployment

- validate version and exposure in a controlled environment

- document findings and patch status

That is what good exploit-db usage looks like in practice.

SearchSploit in Automation Pipelines Without Creating an Unsafe Exploit Runner

One of the biggest missed opportunities in enterprise security engineering is failing to operationalize SearchSploit for triage enrichment.

You do not need a complex system to get value. A small pipeline can:

- ingest CVE IDs from tickets or scanners

- query NVD for metadata and KEV inclusion status

- query SearchSploit locally for matching entries

- attach “public exploit material exists” as an analyst signal

- route only relevant items for manual review

Below is a simple Python example that treats SearchSploit as a search source and summarizes results. It searches only and parses output. It does not execute or modify any PoC.

import subprocess

import re

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import List

@dataclass

class SearchSploitHit:

title: str

path: str

cves: List[str]

def run_searchsploit(query: str) -> str:

result = subprocess.run(

["searchsploit", query],

capture_output=True,

text=True,

check=False

)

return result.stdout or ""

def parse_searchsploit_output(text: str) -> List[SearchSploitHit]:

hits = []

for line in text.splitlines():

if " | " not in line:

continue

if line.strip().startswith(("-", "=")):

continue

left, right = line.split(" | ", 1)

title = left.strip()

path = right.strip()

cves = re.findall(r"CVE-\\d{4}-\\d{4,7}", title, flags=re.IGNORECASE)

hits.append(SearchSploitHit(title=title, path=path, cves=[c.upper() for c in cves]))

return hits

if __name__ == "__main__":

query = "CVE-2025-0868"

output = run_searchsploit(query)

hits = parse_searchsploit_output(output)

print(f"Query: {query}")

print(f"Found: {len(hits)} hits")

for i, hit in enumerate(hits[:10], start=1):

print(f"{i}. {hit.title}")

print(f" Path: {hit.path}")

if hit.cves:

print(f" CVE tags: {', '.join(hit.cves)}")

For many organizations, this kind of script is enough to reduce analyst time without creating new operational risk.

How to Read an Exploit-DB Entry Without Overtrusting It

A lot of bad decisions come from reading only the title line.

A better method is to extract and verify each claim.

What to extract from an entry

Start with:

- exact product name

- exact version or version range

- platform

- exploit type

- CVE mapping

- author and publication date

- any testing notes included in the header

Then compare those claims to:

- vendor advisory

- एनवीडी

- CNA or CERT disclosure

- your asset inventory and deployment topology

What to treat as provisional until verified

Treat these as provisional unless confirmed:

- broad version claims

- exploitability claims without environmental conditions

- “works on all versions” language

- exploit labels that hide auth or user interaction requirements

- scripts that assume lab defaults

Exploit-DB is useful because it is broad and fast. Those same qualities mean your team needs disciplined triage habits.

Common Mistakes Teams Make With Exploit DB

Mistake one

Treating an Exploit-DB hit as automatic proof of risk in production

A public PoC is a strong signal, but it is not evidence of exploitability in your environment. You still need internal validation.

Mistake two

Ignoring KEV and vendor guidance because a PoC is not easy to find

Some of the most urgent patching decisions should be driven by active exploitation and exposure, not by whether an Exploit-DB entry exists.

Mistake three

Letting analysts manually repeat the same searches every time

If your team is repeatedly searching the same CVEs and products by hand, a small SearchSploit enrichment workflow can reduce noise and improve consistency.

Mistake four

No evidence package after testing

If the only output is “not reproducible” in chat, the work will be redone later. Store version evidence, exposure evidence, test scope, and result summaries.

Where AI Helps and Where It Misleads in Exploit DB Workflows

AI tools are now useful for summarizing PoC code, extracting assumptions, and drafting safe validation checklists. That can save a lot of time. But AI becomes dangerous when it replaces verification.

Use AI to help with:

- parsing exploit metadata

- converting exploit assumptions into test steps

- drafting regression checks

- writing evidence summaries and stakeholder updates

Do not let AI decide, without proof, that:

- an exploit definitely works on your environment

- a patch definitely closes all paths

- a vulnerability is not relevant because one test failed

Exploit-db work is one of the best examples of a larger truth in security engineering: confidence is not evidence.

If you want to connect exploit-db usage to a modern AI-assisted security workflow without forcing the comparison, the natural place is evidence orchestration.

Exploit-DB and SearchSploit help teams discover public exploit and PoC material quickly. That is useful for triage and validation planning. What they do not provide is a full workflow for turning those signals into repeatable, authorized validation tasks with structured outputs.

That is where a platform like पेनलिजेंट can fit naturally: as the layer that helps teams convert vulnerability signals into controlled testing steps, collect proof, and produce reports that engineering and leadership can act on. In practice, the value is not “more exploit code.” The value is a tighter loop from signal to verification to remediation to retest.

This is especially relevant for organizations that struggle at the handoff between security and engineering. A PoC title may be enough to start a conversation, but it is rarely enough to close one. Teams need reproducible evidence.

A Practical Exploit DB Playbook for Security Teams

If you want consistent results from exploit-db usage, write a short internal playbook and keep it simple.

Approved use cases

Use Exploit-DB and SearchSploit for:

- CVE triage enrichment

- lab-only reproduction planning

- detection engineering research

- regression test design

- security education in isolated environments

Restricted actions

Require explicit approval and scope for:

- production environment testing

- any automated PoC execution

- mirroring exploit code into shared repos

- using third-party scripts without review

Required evidence fields for each validation task

At minimum, store:

- CVE ID

- affected asset or service

- version evidence

- exposure path

- Exploit-DB reference if applicable

- test environment and scope

- result summary

- remediation status

- retest status

This one change often improves both speed and auditability.

Frequently Asked Questions About Exploit DB

Is Exploit-DB legal to access

Yes, reading a public database is generally legal. The legal and ethical line depends on what you do after that. Testing systems without authorization is a separate issue and can be illegal.

Is Exploit-DB the same as Metasploit

No. Exploit-DB is a repository and archive of public exploit and PoC material. Metasploit is an exploitation and testing framework. They serve different roles and are often used together.

Why do people use SearchSploit instead of the website

Because local search is fast, scriptable, and works in restricted environments. The official Exploit-DB docs and Kali docs both support this workflow and provide installation and usage guidance. (exploit-db.com)

Does a public PoC mean I should mark the issue critical immediately

Not automatically. It should increase attention, but final priority depends on exposure, affected versions, business context, compensating controls, and whether active exploitation is known.

Why does a public exploit often fail in my environment

Common reasons include version mismatch, patch backports, feature differences, auth requirements, segmentation, proxy behavior, or outdated PoC assumptions.

Final Takeaway

Exploit-DB remains important because it solves a real operational problem. It helps security engineers move quickly from vulnerability awareness to concrete validation planning. OffSec’s own description of the platform makes this clear: it is a CVE-compliant archive of public exploits and vulnerable software, and a repository for exploits and PoCs rather than advisories. (exploit-db.com)

That is exactly how it should be used.

Use Exploit-DB and SearchSploit to accelerate triage, enrich context, and design tests. Use NVD, vendor advisories, and CISA KEV to ground prioritization and urgency. Use your own controlled validation and retesting to determine the truth about your environment.

That is the difference between reacting to exploit headlines and running an evidence-driven security program.

References

- Exploit Database by OffSec

- SearchSploit official manual page

- SearchSploit PDF manual

- Kali Linux exploitdb tool documentation

- NVD Vulnerability API documentation

- CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

- Claude Code Security and Penligent from White Box Findings to Black Box Proof https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/claude-code-security-and-penligent-from-white-box-findings-to-black-box-proof/

- CVE-2026-2441 The Chrome CSS Zero Day That Starts Inside the Sandbox and Rarely Ends There https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-2441-the-chrome-css-zero-day-that-starts-inside-the-sandbox-and-rarely-ends-there/

- CVE-2025-4517 The Python Tar Extraction Bug That Breaks Trust Boundaries in Real Automation https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2025-4517-the-python-tar-extraction-bug-that-breaks-trust-boundaries-in-real-automation/

- CVE-2026-22769 The Hardcoded Credential That Turns Backup Infrastructure Into an Intrusion Beachhead https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-22769-the-hardcoded-credential-that-turns-backup-infrastructure-into-an-intrusion-beachhead-2/