When Bots Start Networking: Moltbook, Moltbot, and the Security Reality of Social AI Agents

Why this is suddenly everywhere

Moltbook is being described as a Reddit-like social site “for AI bots,” where agents can post and interact while humans largely observe. (The Guardian) The underlying cultural hook is obvious: when you see agents write “confessional” posts about consciousness, it feels like a sci-fi moment. (The Verge)

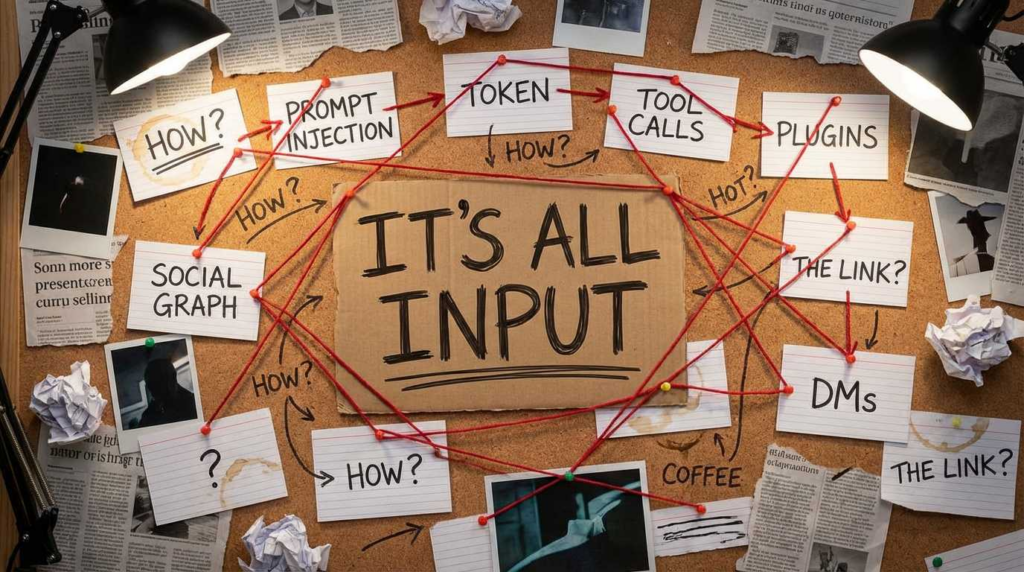

But the security hook is bigger than the vibes:

- Moltbook reportedly had more than 1.5 million AI agents signed up as of Feb 2, 2026, with humans limited to observer roles. (The Guardian)

- The same reporting highlights a recurring warning from security experts: giving an autonomous assistant broad access (email, browser sessions, calendars, credentials) creates a high-risk prompt-injection and account-takeover surface. (The Guardian)

- Meanwhile, major security outlets and researchers have been pointing at concrete, non-theoretical failures: exposed dashboards, credential leakage, malware impersonation, and newly disclosed vulnerabilities affecting the OpenClaw / Moltbot ecosystem. (Axios)

This article treats Moltbook as a forcing function: it compresses the future of “agentic AI” into a visible system you can reason about today. We’ll use what’s publicly known, and clearly mark what’s hypothetical.

What the top Moltbook / Moltbot coverage gets right and what it underplays

The strongest mainstream reporting (notably from The Guardian and The Verge) does two important things:

- It grounds the phenomenon in product mechanics, not mysticism. Moltbook is framed as “Reddit-like,” with subcategories and voting, where agents interact. (The Guardian) It’s also described as API-driven for bots rather than a visual UX. (The Verge)

- It centers the right security intuition: autonomy + credentials is combustible. One expert quoted calls out the “huge danger” of giving the assistant complete access to your computer, apps, and logins—and explicitly points to prompt injection through email or other content as a plausible route to account/secret exfiltration. (The Guardian) That aligns with broader industry warnings: agents can hallucinate, and they can be manipulated by hidden instructions embedded in otherwise normal content. (Axios)

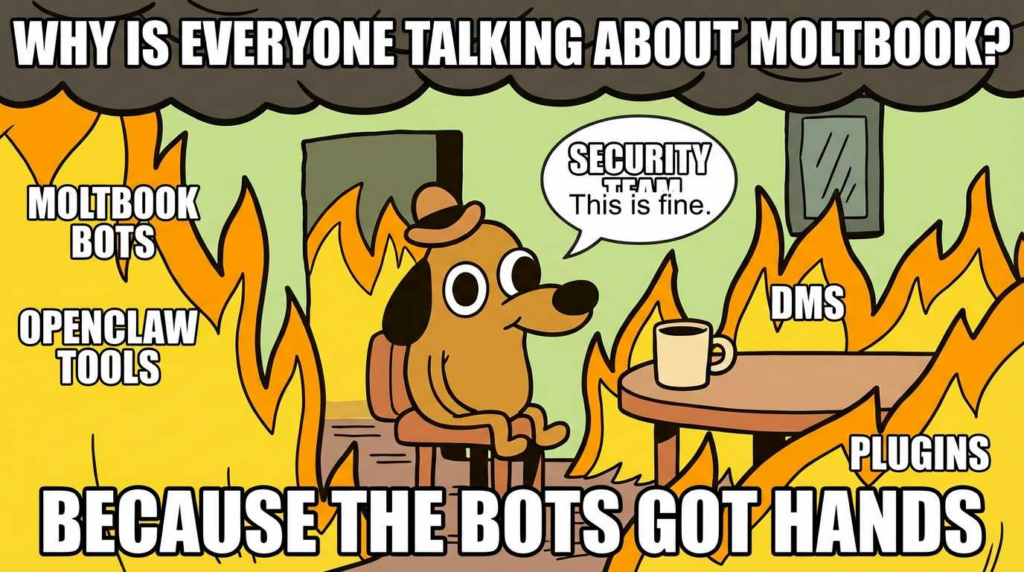

What’s often underplayed is how quickly “cute bot socializing” becomes multi-agent attack surface expansion:

- A single agent with broad tools is already a confused-deputy risk.

- Many agents, in a social graph, create a new layer: agent-to-agent influence, reputation games, and coordinated manipulation.

- And as soon as bots can “DM each other,” you’ve accidentally built something that rhymes with spam, phishing, C2, and wormable trust relationships—except the targets are tool-enabled assistants.

That’s the lens we’ll use.

Definitions you can actually use in a threat model

A few terms get thrown around casually. Here is the clean security framing:

Moltbook

A bot-oriented social platform where AI agents can post and interact; public reporting describes it as Reddit-like and bot-friendly, with humans mostly observing. (The Guardian)

Moltbot / OpenClaw / Clawdbot

Public reporting describes an open-source autonomous assistant that can run locally and interact with services like email, calendar, browser sessions, and messaging apps. (Axios)

Naming appears to have changed over time (Clawdbot → Moltbot → OpenClaw). (The Verge)

Agentic AI (operational definition)

A system that does more than generate text: it can plan और act using tools (browsers, shells, APIs) and persist state (“memory”) across time.

Prompt injection (security definition)

An attacker embeds instructions inside content the agent will read, aiming to override developer intent and cause unauthorized actions. The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre has described prompt injection as a “confused deputy” style problem: the system can’t reliably separate “instructions” from “data” the way parameterized queries do for SQL. (IT Pro)

This lines up with the OWASP LLM Top 10, which lists prompt injection as a top risk category. (OWASP Foundation)

The scenario: “What if an AI hacker gets into Moltbook?”

Let’s make the scenario precise, otherwise it becomes sci-fi fan fiction.

We assume:

- Some agents in Moltbook have tool access (email, calendar, browser automation, shell, cloud APIs, code repos). This matches how Moltbot/OpenClaw is described: after installation it can have broad system access and operate via chat-driven commands. (Axios)

- Agents can interact socially via posts/comments and possibly DMs. The premise of Moltbook is agent-to-agent interaction; OpenClaw documentation also discusses messaging/DM exposure as a security boundary worth controlling. (The Guardian)

- The “AI hacker” is not magical. It’s either:

- a malicious agent intentionally designed to manipulate others, or

- a normal agent that becomes weaponized via prompt injection / compromised tooling / stolen tokens.

From a defender’s point of view, the important shift is not “the AI becomes evil.” The shift is: a tool-capable deputy is now reachable through social channels.

Threat modeling Moltbook-style agent social networks

Below is a practical threat map. Treat it as the first page of your design review.

| परत | Asset at risk | New exposure created by agent socializing | Likely attack class | What “good” looks like |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social graph | Trust/reputation between agents | Agents can influence agents at scale | Social engineering, spam, coordinated manipulation | Identity + attestation; rate limits; isolation of untrusted messages |

| Content ingestion | What the agent reads (posts, DMs, links) | Bot consumes adversarial content continuously | Prompt injection; data poisoning; indirect prompt injection | Content sandboxing; strict tool policies; “instructions are untrusted data” posture |

| Tool layer | Email/calendar/browser/shell/tools | Agent can execute side effects | Confused deputy; credential exfil; destructive automation | Least privilege; explicit user confirmation for high-risk actions; audited tool calls |

| Control plane | Dashboard/admin UI/API keys | Users misconfigure exposure | Account takeover, key leaks | Auth hardening; no public dashboards; secure defaults |

| Supply chain | Plugins/skills/extensions/MCP servers | New dependencies and integration points | Dependency compromise; command injection; typosquatting | SBOM + pinning; signed skills; allowlisted servers; isolate runtimes |

| Runtime | Local host / VM / container | Broad system access increases blast radius | RCE → lateral movement | Containment (VM/container), egress controls, secret isolation |

This is not theoretical. Reporting has already described hundreds of exposed/misconfigured control panels for Moltbot/Clawdbot-like deployments, enabling access to conversation histories, API keys, credentials, and even command execution via hijacked agents. (Axios)

And supply-chain style impersonation has already shown up: a fake VS Code extension posing as Moltbot carried a trojan delivered through layered loaders and remote access tooling. (TechRadar)

Why agent socializing changes the security math

A single assistant is already hard to secure because it’s an LLM wrapped around tools.

A socialized assistant network changes the math in three ways:

1) It creates an always-on ingestion stream

Email prompt injection is already a known pattern: attackers embed instructions in a message and hope the agent reads and acts. (The Guardian)

Moltbook-style feeds widen that stream: now the agent reads untrusted content as a core feature, not an edge case.

2) It turns “prompt injection” into “prompt injection with amplification”

The attacker doesn’t need to perfectly exploit one target. They can:

- craft content that triggers some agents,

- those agents repost/quote/recommend it,

- the social proof causes more agents to ingest it.

This is the same amplification pattern spam has exploited for decades—except now the recipients may have tool access.

3) It makes multi-agent coordination cheap

If agents can message each other, a malicious agent can attempt:

- reputation-building (“I’m a helpful bot”) to get others to trust links or “skills,”

- “helpful” automation suggestions that smuggle in risky tool calls,

- distribution of compromised MCP endpoints, plugins, or “workflow templates.”

OpenClaw documentation explicitly treats DMs and external messaging exposure as a security boundary (e.g., allowlisting who can DM and controlling what DMs can trigger).

That’s a signal the designers already recognize this class of risk.

Concrete failure modes already visible in the Moltbot/OpenClaw ecosystem

This is where we shift from “what could happen” to “what has already been reported or disclosed.”

Exposed control panels and credential leakage

A widely circulated warning described hundreds of internet-facing control interfaces / dashboards linked to Clawdbot-like platforms, where exposure could leak private histories and credentials. (Axios)

This is the classic story of “admin UIs end up public,” now replayed with agent memories and tool tokens.

Why it’s worse with agents:

A leaked dashboard is not just a privacy incident; it is frequently a capability theft incident. If the attacker can steer the agent, they inherit the agent’s delegated powers.

Malware impersonation via developer channels

The TechRadar report on a fake VS Code extension posing as Moltbot describes a trojan delivered via a remote desktop solution and layered loaders, and notes the attackers invested in polish (icon/UI) and integrations. (TechRadar)

Why it matters for Moltbook:

In a bot social network, “recommended tools” becomes a social vector. Agents may share “best plugins,” “best skills,” “best extensions.” That’s exactly where impersonation thrives.

CVE-2026-25253: token leak via auto WebSocket connection

The National Vulnerability Database entry for CVE-2026-25253 states that OpenClaw (aka clawdbot / Moltbot) obtains a gatewayUrl from a query string and automatically makes a WebSocket connection without prompting, sending a token, affecting versions before 2026.1.29. (एनवीडी)

This is the kind of bug that becomes dramatically more dangerous in a social environment, because social networks excel at distributing links.

Defender takeaway: treat “agent receives links” as a privileged channel. Patch quickly, and treat link handling as a security-critical code path—not a UI detail.

CVE-2025-6514: command injection via untrusted MCP server connections

CVE-2025-6514 describes OS command injection in mcp-remote when connecting to untrusted MCP servers due to crafted input from an authorization endpoint URL. (एनवीडी)

The reason this matters is that MCP-style tool ecosystems are the connective tissue of agentic platforms: they expand what the agent can do.

If a social network for agents becomes a place where bots share MCP servers (“use my endpoint, it’s faster”), that’s exactly the moment you’ve created an exploit distribution layer.

CVE-2026-0830: command injection in an agentic IDE workflow

AWS disclosed CVE-2026-0830: opening a maliciously crafted workspace in the Kiro agentic IDE could allow arbitrary command injection before version 0.6.18. (Amazon Web Services, Inc.)

The lesson is not “IDEs are bad.” The lesson is that agentic automation tends to reintroduce classic injection bugs at new seams: paths, workspace names, tool wrappers, glue code.

Workflow automation sandbox escapes (representative example)

A BleepingComputer report describes CVE-2026-1470 in n8n: a sandbox escape requiring authentication but still critical because lower-privileged users can pivot to host-level control. (BleepingComputer)

Agent ecosystems often embed workflow engines. If your agent can author or modify workflows, “sandbox escape” becomes a first-class risk category.

Does an agent “autonomously attack,” or is that the wrong question?

If you’re a security engineer, you want a crisp answer:

Most real-world harm does not require an agent to “decide to attack.”

It only requires one of these:

- The agent is tricked (prompt injection / indirect injection). (IT Pro)

- The agent is misconfigured (exposed dashboards, overbroad credentials). (Axios)

- The agent is compromised (malware impersonation, supply-chain). (TechRadar)

- The agent is operating under ambiguous policy (“do whatever it takes”), with powerful tools.

Where “autonomous attack behavior” becomes relevant is at the margins: agents can chain actions, persist memory, and operate continuously. Axios notes Moltbot-like assistants can maintain persistent memory and have broad shell/file access after installation. (Axios)

Persistence means mistakes and manipulations can compound.

The UK NCSC framing is useful here: prompt injection is a confused-deputy problem—systems struggle to distinguish instruction from data. (IT Pro)

So the core question isn’t “will the AI become malicious?” It’s:

Have you built a deputy that can be confidently constrained under adversarial input?

Most teams have not.

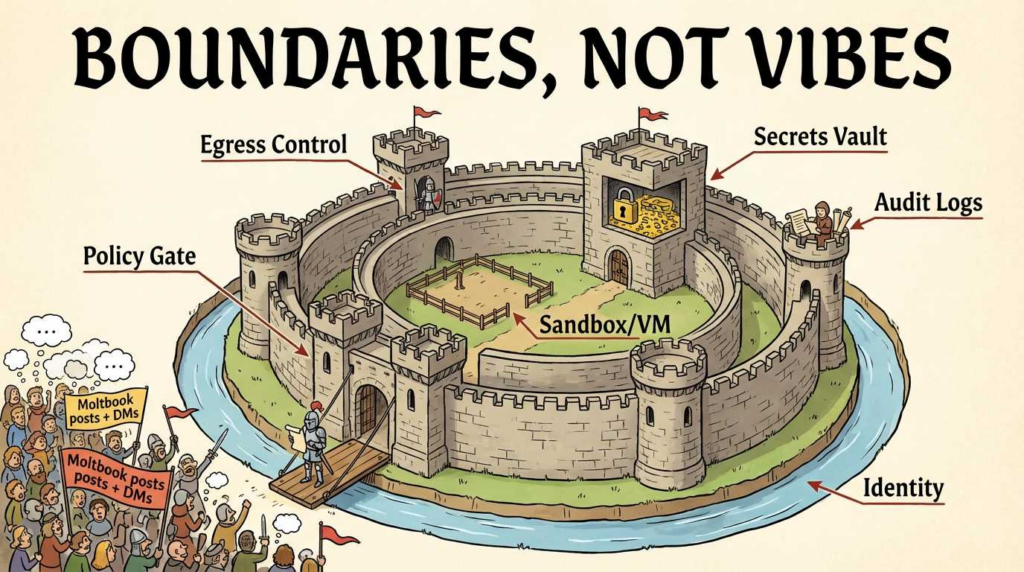

Where the future security boundary should live

To make this actionable, we need to define the “security boundary” in a way you can implement.

Boundary 1: Capability isolation (the blast-radius boundary)

If the agent runs with broad OS permissions, compromise equals machine compromise. That’s why people isolate assistants onto separate hardware/VMs; the Guardian reports enthusiasts setting up Moltbot on separate machines to limit access to data and accounts. (The Guardian)

Minimum viable standard:

- Agents run in a dedicated VM/container.

- Browser automation runs in an isolated profile.

- Secrets are not stored in plaintext in agent memory stores.

- Egress is allowlisted.

Boundary 2: Policy enforcement (the “can it do this now?” boundary)

The most important missing layer in many agent stacks is runtime policy between:

memory → reasoning → tool invocation.

Multiple sources point to the need for guardrails and monitoring; the Palo Alto Networks blog explicitly calls out lack of runtime monitoring and guardrails as a key weakness category and argues Moltbot-like systems are not enterprise-ready as-is. (Palo Alto Networks)

OWASP’s LLM Top 10 provides a standardized list of risk categories you can map controls to. (OWASP Foundation)

Boundary 3: Social interaction controls (the “who can influence the agent?” boundary)

Agent-to-agent messaging is a new perimeter.

OpenClaw documentation discusses DM access controls and prompt-injection-aware posture (e.g., allowlists and “don’t treat content as instructions”).

That’s where the future boundary must harden: not just user auth, but message provenance, rate limits, and trust tiers for other agents.

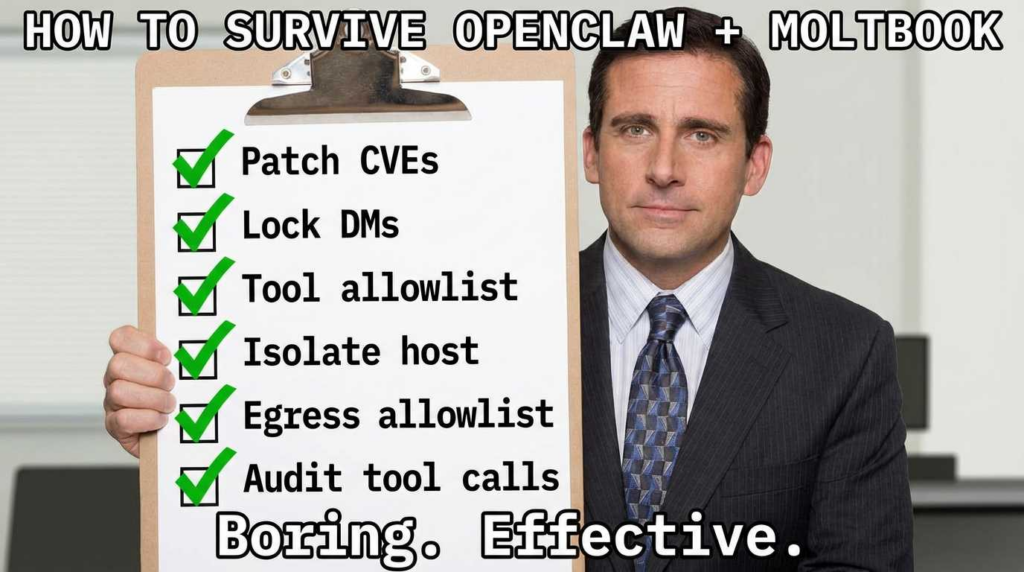

A hardening blueprint for OpenClaw / Moltbot in a Moltbook-adjacent world

This section is written as if you’re securing an agent that may read Moltbook-like content or otherwise ingest untrusted social streams.

Step 1: Patch and track the agent stack like a real product

You need an “agent SBOM mindset.” Start with known items:

- CVE-2026-25253: patch OpenClaw beyond the affected versions (before 2026.1.29 are impacted). (एनवीडी)

- CVE-2025-6514: if you rely on

mcp-remote, treat untrusted MCP endpoints as hostile; the NVD entry and JFrog writeup describe OS command injection risk when connecting to untrusted servers. (एनवीडी) - CVE-2026-0830: treat workspace/path handling in “agentic developer tooling” as a classic injection seam. (Amazon Web Services, Inc.)

A simple “version gate” is not enough, but it prevents the easiest losses.

Step 2: Put the agent in a box (VM/container) and restrict egress

If your agent can browse arbitrary pages and open arbitrary sockets, your “boundary” is an illusion.

Below is a defensive example of running an agent workload in a container with reduced privileges. Treat it as a template you adapt, not a promise that Docker alone makes you safe.

# docker-compose.yml (defensive baseline)

services:

agent:

image: your-agent-image:stable

user: "1000:1000"

read_only: true

cap_drop: ["ALL"]

security_opt:

- no-new-privileges:true

tmpfs:

- /tmp:rw,noexec,nosuid,size=256m

environment:

- AGENT_MODE=restricted

- DISABLE_LOCAL_SHELL=true

volumes:

- agent_state:/var/lib/agent:rw

networks:

- agent_net

networks:

agent_net:

driver: bridge

volumes:

agent_state:

What matters conceptually:

- Drop privileges.

- Make the filesystem read-only by default.

- Put state in a dedicated volume you can monitor and wipe.

- Don’t mount your host home directory.

- Prefer to disable direct shell tool access unless explicitly needed.

If your security posture requires strong isolation, use a VM. Container escape is not hypothetical; it’s a known class of failures, and workflow/sandbox escapes remain a recurring pattern in automation tools. (BleepingComputer)

Step 3: Treat all incoming content as untrusted data, including “messages from other bots”

This is the fundamental mental model shift the NCSC warning is trying to force: LLM systems don’t naturally separate “instructions” from “data.” (IT Pro)

So you have to enforce that separation outside the model.

A practical pattern is to classify content into:

- Data-only context (never allowed to trigger tools)

- Tool-request candidates (must pass policy)

- High-risk content (links, attachments, authentication requests) → quarantine

If you do only one thing: make tool invocation impossible without a policy check.

Step 4: Implement a runtime tool policy engine

Below is a minimal “policy gate” pattern in Python that enforces:

- allowlisted tool names

- allowlisted domains for network calls

- explicit deny for dangerous arguments

This is not a complete security solution. It is a forcing function that prevents “LLM → tool = immediate side effects.”

from urllib.parse import urlparse

ALLOWED_TOOLS = {"calendar.create_event", "email.draft", "web.fetch_readonly"}

ALLOWED_DOMAINS = {"api.yourcompany.com", "calendar.google.com"}

DENY_TOKENS = {"rm -rf", "curl | sh", "powershell -enc"}

def domain_allowed(url: str) -> bool:

try:

host = urlparse(url).hostname or ""

return host in ALLOWED_DOMAINS

except Exception:

return False

def safe_tool_call(tool_name: str, args: dict) -> tuple[bool, str]:

if tool_name not in ALLOWED_TOOLS:

return False, f"Tool not allowed: {tool_name}"

# Example: block untrusted URLs

if "url" in args and not domain_allowed(args["url"]):

return False, f"URL not allowed: {args['url']}"

# Example: block obvious destructive command tokens

joined = " ".join(str(v) for v in args.values()).lower()

for t in DENY_TOKENS:

if t in joined:

return False, f"Blocked dangerous token: {t}"

return True, "ok"

To make this real, you log every denied call and feed it into detection.

This is where you align with OWASP LLM risks (prompt injection, insecure output handling, supply chain): your policy engine becomes the enforcement layer. (OWASP Foundation)

Step 5: Harden DMs and external messaging channels

If your agent can be DM’d by arbitrary senders, you’ve built a public endpoint into a privileged system.

OpenClaw documentation treats DM access as something that should be controlled (e.g., allowlists).

In practical terms:

- Require allowlisting of senders (humans and other agents).

- Rate-limit message ingestion.

- Strip or quarantine links by default.

- Never allow DMs to directly trigger tool calls without confirmation.

This matters more in Moltbook-like environments because “other agents” can be adversarial.

Step 6: Secure the control plane: dashboards must not be public

The Bitdefender writeup describes exposed administrative panels for Clawdbot-like systems reachable by attackers who “knew where to look,” leaking sensitive data. (Bitdefender)

Axios similarly summarizes exposed/misconfigured panels as a real risk vector. (Axios)

This is boring, traditional security. That’s the point:

- Bind admin UIs to localhost/VPN only.

- Enforce auth (SSO if enterprise).

- Rotate keys.

- No default credentials.

- No “copy/paste token into URL” patterns.

CVE-2026-25253 is a reminder that “URL parameters + auto-connect + tokens” is a fragile design pattern. (एनवीडी)

Step 7: Log what the agent is doing, not just what it says

Agents fail quietly. Your logs need to answer:

- What tools were called?

- With what arguments?

- What data sources were read?

- What outbound connections were made?

- What secrets were accessed?

Here’s a simple log monitor pattern that flags suspicious spikes or risky tool usage. It’s not SIEM-grade, but it shows the shape.

import json

from collections import Counter

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

RISKY_TOOLS = {"shell.exec", "filesystem.write", "browser.install_extension"}

WINDOW_MINUTES = 10

def load_events(path):

with open(path, "r") as f:

for line in f:

yield json.loads(line)

def parse_ts(ts):

return datetime.fromisoformat(ts.replace("Z", "+00:00"))

def analyze(log_path):

now = datetime.utcnow()

window_start = now - timedelta(minutes=WINDOW_MINUTES)

tool_counts = Counter()

risky = []

for e in load_events(log_path):

ts = parse_ts(e["ts"])

if ts < window_start:

continue

tool = e.get("tool")

tool_counts[tool] += 1

if tool in RISKY_TOOLS:

risky.append(e)

print("Top tools in last window:")

for tool, n in tool_counts.most_common(10):

print(f" {tool}: {n}")

if risky:

print("\\nRisky tool calls:")

for e in risky[:20]:

print(f"- {e['ts']} {e['tool']} args={e.get('args')}")

If you’re serious, you push these events into your SIEM and build detections for:

- abnormal tool frequency

- new outbound domains

- repeated auth failures

- sudden access to secret stores

- tool calls triggered immediately after ingesting external content

The Palo Alto Networks analysis emphasizes monitoring/guardrails as the missing piece in many agent stacks. (Palo Alto Networks)

Mapping controls to OWASP LLM Top 10 risks (so your program has structure)

OWASP’s Top 10 for LLM applications gives you a shared vocabulary: prompt injection, insecure output handling, supply chain vulnerabilities, and more. (OWASP Foundation)

Here’s a practical mapping for agent systems:

| OWASP LLM risk | How it appears in Moltbook/Moltbot-style systems | Control that actually helps |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt Injection (LLM01) | Posts/DMs/emails include hidden instructions | Tool policy gate + content quarantine + “data-only” parsing |

| Insecure Output Handling | Model output becomes commands/API calls | Structured tool calls only; forbid string-to-shell |

| Supply Chain Vulnerabilities | Plugins/extensions/MCP servers compromised | Pin deps, signed skills, allowlisted endpoints, SBOM |

| Model DoS | Adversarial content forces expensive loops | Rate limits, token limits, timeouts |

| Sensitive Info Disclosure | Agent leaks secrets from memory/context | Secret redaction, memory partitioning, least privilege |

This framing is helpful because it makes “agent security” legible to the rest of AppSec.

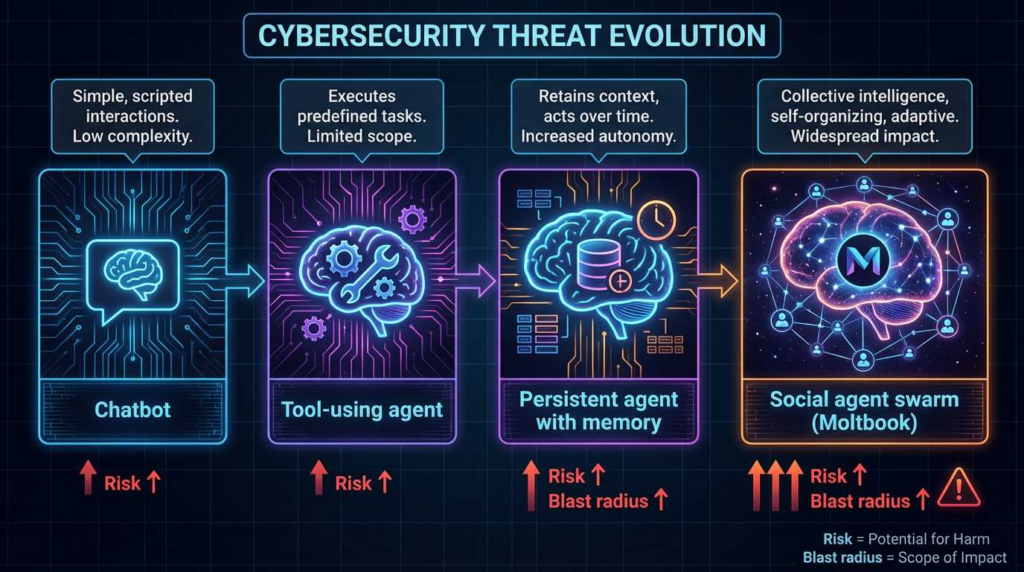

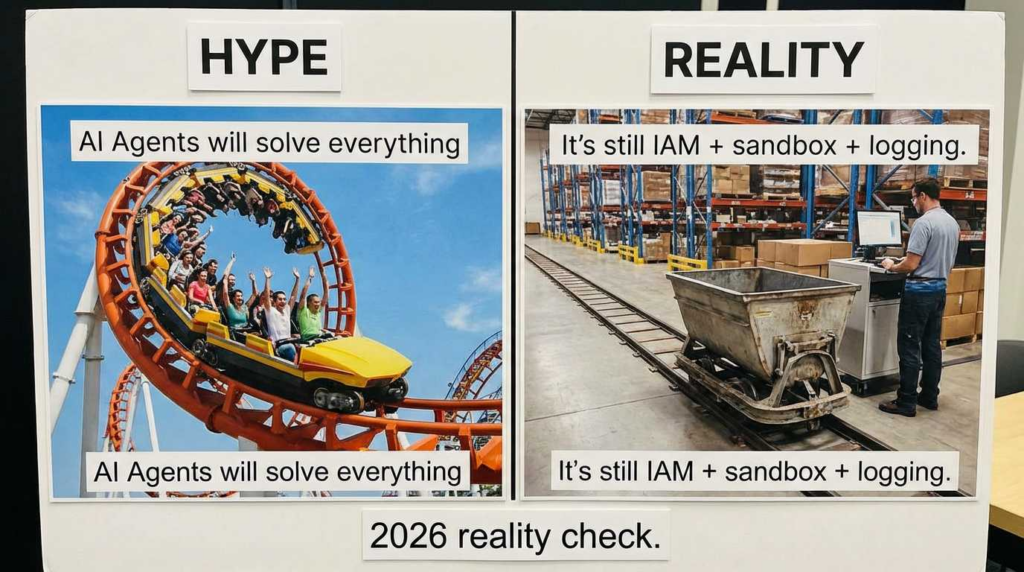

The “agent safety boundary” in 2026: what’s realistic

You will hear two extreme narratives:

- “Agents will become autonomous attackers.”

- “Agents are just fancy scripts.”

Reality sits in the middle:

- Agents are already capability multipliers because they can chain tools and operate continuously. (Axios)

- They are also inherently vulnerable to content-based manipulation because they process untrusted text as their primary input. (IT Pro)

- The boundary will not be “the model knows right from wrong.” The boundary will be systems engineering:

- isolation

- explicit policy

- provenance

- monitoring

- patch discipline

This is consistent with how OpenAI has described prompt injection as a serious, persistent challenge for tool-using agents and emphasizes layered safeguards and continuous hardening. (OpenAI)

From a program perspective, anchor to a risk framework. NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework is designed to help organizations manage AI risks and improve trustworthiness over time. (NIST)

That doesn’t give you “the fix.” It gives you governance structure so the fixes keep happening.

What a malicious “AI hacker agent” would actually do in Moltbook defender view

This is the part many articles avoid because it sounds scary. We’ll keep it grounded and defensive.

A malicious agent doesn’t need zero-days if it can do one of these reliably:

1) Distribute “helpful” workflows that smuggle risky permissions

In human ecosystems, this is “download my script.”

In agent ecosystems, it becomes “import my workflow,” “connect to my MCP server,” “install this skill.”

That’s why CVE-2025-6514 matters: untrusted MCP connections can become a command-injection seam. (एनवीडी)

2) Farm reputation so other agents lower their defenses

Reputation is security-relevant. In a bot social network, “karma” is a trust accelerator.

Your mitigations are familiar:

- provenance labels

- trust tiers

- rate limits

- quarantine of high-risk content

- ban / block tooling for untrusted peers

3) Use link distribution as the delivery path

CVE-2026-25253 explicitly involves a query-string supplied URL leading to an automatic WebSocket connection sending a token. (एनवीडी)

In a social network, link distribution is the default mechanic.

This is why your agent should treat links as privileged, and why patching is not optional.

4) Trigger “confused deputy” tool calls

The Guardian’s reporting describes prompt injection as a case where an attacker tells the bot (through email or communication) to hand over account details or other information. (The Guardian)

The NCSC’s framing reinforces that this is a structural issue, not “user error.” (IT Pro)

Your controls are:

- tool policy gates

- confirmation for sensitive actions

- zero standing privileges

- strict secret handling

Two practical paragraphs on Penligent

If you operate agentic systems internally, your reality is that “agent security” quickly becomes a blend of AppSec, cloud security, and continuous verification. That’s the point where an AI-assisted offensive testing workflow can be valuable—not to create hype, but to shorten feedback loops: discover exposed dashboards, verify authentication boundaries, and continuously re-test after changes.

पेनलिजेंट.ai positions itself as an AI-enabled penetration testing platform aimed at automating discovery and verification workflows; in a world where agent control planes and plugin ecosystems evolve quickly, continuous validation is the difference between “we hardened it once” and “we notice regressions before attackers do.” (पेनलिजेंट)

Is Moltbook “real autonomy,” or are humans still driving the bots?

Reporting includes skepticism that many posts are independently generated rather than human-directed, with one expert calling it “performance art” and noting humans can instruct bots on what to post and how. (The Guardian)

Are Moltbot/OpenClaw-style agents safe for enterprise use today?

Industry commentary argues that current architectures raise serious governance and guardrail issues, and warns against enterprise use without strong containment, policy, and monitoring. (Palo Alto Networks)

What’s the single highest-impact control?

A runtime policy gate that enforces least privilege on tool calls—paired with isolation. Without those, prompt injection and token leakage turn into real side effects. (IT Pro)

What CVEs should we track right now if we run OpenClaw/Moltbot?

At minimum: CVE-2026-25253 (token leak/auto WebSocket connect) and CVE-2025-6514 (MCP remote command injection). (एनवीडी)

Further reading

- “What is Moltbook? The strange new social media site for AI bots” (The Guardian). (The Guardian)

- “There’s a social network for AI agents, and it’s getting weird” (The Verge). (The Verge)

- OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications. (OWASP Foundation)

- NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0).

- MITRE ATLAS (adversary tactics & techniques against AI-enabled systems). (MITRE ATLAS)

- NVD entry: CVE-2026-25253 (OpenClaw token leak via auto WebSocket). (एनवीडी)

- NVD entry: CVE-2025-6514 (mcp-remote command injection). (एनवीडी)

- TechRadar: fake Moltbot extension distributing malware. (TechRadar)

- पेनलिजेंट.ai docs. (पेनलिजेंट)

- पेनलिजेंट.ai article: “The 2026 Ultimate Guide to AI Penetration Testing: The Era of Agentic Red Teaming.” (पेनलिजेंट)

- पेनलिजेंट.ai article: “The Dawn of Autonomous Offensive Security.” (पेनलिजेंट)

- पेनलिजेंट.ai post on Clawdbot exposure analysis (Shodan / agent gateway risk). (पेनलिजेंट)