If you work in application or AI-driven security long enough, “IDOR” stops being just another buzzword and turns into a recurring pattern you see everywhere: APIs, mobile backends, SaaS dashboards, admin panels, even internal tooling.

CVE-2025-13526 is one of those cases where an Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) is not hiding deep inside an exotic protocol—but sitting in a widely deployed WordPress plugin, quietly exposing customer data to anyone willing to tweak a URL parameter.(wiz.io)

This article takes a hard look at IDOR as a class, and uses CVE-2025-13526 as a concrete, modern example. The goal is not just to recap “there was a bug in a plugin,” but to extract practical lessons for how we design, test, and automate security in an AI-first world.

IDOR and Broken Object-Level Authorization, Without the Buzzword Fog

In OWASP API Security 2023, the very first item—API1: Broken Object Level Authorization—is effectively the API-era name for what most of us still call IDOR.(OWASP)

The mechanics are painfully simple:

- The application exposes some kind of object identifier in the request:

order_id,user_id,ticket_id,message_id, and so on. - The backend uses that identifier to look up a record.

- Somewhere between decoding the ID and returning data, no one asks “is this caller allowed to access this object?”

OWASP’s API1 and write-ups from API security teams like apisecurity.io and Traceable describe the same core idea: an attacker replaces the ID of their own object with another ID—sequential integer, UUID, whatever—and the application cheerfully returns someone else’s data.(API Security News)

MITRE’s CWE-639 (Authorization Bypass Through User-Controlled Key) captures this pattern formally, and even notes that the term “IDOR” overlaps heavily with Broken Object Level Authorization (BOLA).(CWE)

IDOR is not clever. It does not require a PhD or a chain of deserialization gadgets. It is dangerous because:

- It’s easy to introduce during rapid product iteration.

- It often slips past superficial testing.

- It scales beautifully for attackers: a single endpoint, a simple script, thousands of records.

CVE-2025-13526 is, unfortunately, a textbook instance.

CVE-2025-13526 at a Glance: IDOR in a WordPress “Chat to Order” Plugin

According to Wiz, Wordfence, OpenCVE and other trackers, CVE-2025-13526 is an IDOR in the OneClick Chat to Order plugin for WordPress. All versions up to and including 1.0.8 are affected; the issue was fixed in 1.0.9.(wiz.io)

The vulnerable function is named wa_order_thank_you_override. After a successful checkout, customers are redirected to a “thank you” page whose URL includes an order_id parameter. The function takes that parameter, looks up the order, and renders a summary—without verifying that the current visitor is actually the owner of that order.

Multiple sources converge on the same impact: an unauthenticated attacker can alter the order_id in the URL and view other customers’ order details, including personally identifiable information.(wiz.io)

CVE-2025-13526: Key Properties

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| CVE ID | CVE-2025-13526 |

| Product | OneClick Chat to Order WordPress plugin |

| Affected versions | ≤ 1.0.8 |

| Fixed in | 1.0.9 |

| Vulnerability type | IDOR / Broken Object Level Authorization (BOLA) |

| CWE mapping | CWE-200 (Information Exposure), CWE-639 (User-Controlled Key) |

| Attack vector | Network (remote), unauthenticated |

| Complexity | Low (simple parameter tampering) |

| Impact | Exposure of customer PII and order content |

| CVSS v3.1 | 7.5 (High) AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:N/A:N |

| Primary references | NVD, CVE.org, Wiz, Wordfence, Positive Technologies, OpenCVE |

NVD and CVE.org list the vulnerability as “Exposure of Sensitive Information to an Unauthorized Actor” (CWE-200), with a CVSS 7.5 high score.(NVD) Wordfence’s advisory is even more blunt:

“OneClick Chat to Order <= 1.0.8 – Insecure Direct Object Reference to Unauthenticated Sensitive Information Exposure.”(Wordfence)

In other words: no login required, just an order_id in the URL.

Under the Hood: How This IDOR Actually Works

Let’s strip away branding and look at the core pattern.

Imagine a typical WooCommerce-style thank-you URL:

<https://shop.example.com/checkout/thank-you/?order_id=12345>

In vulnerable versions of OneClick Chat to Order, when a user hits this URL:

- The plugin reads

$_GET['order_id']. - It asks the e-commerce backend (e.g., WooCommerce) for order

12345. - It renders a “thank you / order summary” page based entirely on that order object.

- It never checks whether the current visitor is authenticated, or whether they own order

12345.

A simplified version of that logic might look like this:

// Vulnerable pseudocode for illustration only

function wa_order_thank_you_override() {

$order_id = $_GET['order_id'] ?? null;

if (!$order_id) {

return; // or redirect somewhere

}

// Fetch order by ID

$order = wc_get_order($order_id);

if (!$order) {

return; // order not found

}

// ❌ Missing: check that the current user is allowed to see this order

// Render "thank you" view with order details

render_wa_thank_you_page($order);

}

From there, exploitation is obvious:

- The attacker loads one thank-you URL (maybe their own order, maybe a guessed ID).

- They increment or decrement

order_idand refresh. - For each valid ID, the application returns another customer’s name, email, phone, addresses, and order contents.

Because the endpoint does not require an authenticated session, the bar is even lower: a completely unauthenticated attacker can enumerate orders by ID.

What the Fix Looks Like

The fix is, structurally, what most of us already know we should do: tie object access to the authenticated user (or a secure token linked to that user) and centralize the logic.

Conceptually, a more robust version looks like:

// Hardened pseudocode for illustration only

function wa_order_thank_you_override() {

$order_id = $_GET['order_id'] ?? null;

if (!$order_id) {

return;

}

$order = wc_get_order($order_id);

if (!$order) {

return;

}

// Enforce ownership: either logged-in customer or verified guest

if (!current_user_can_view_order($order)) {

wp_die(__('You are not allowed to view this order.', 'oneclick-chat-to-order'), 403);

}

render_wa_thank_you_page($order);

}

function current_user_can_view_order($order) {

$user_id = get_current_user_id();

if ($user_id) {

// Logged-in customer: only allow if this is their order

return (int) $order->get_user_id() === (int) $user_id

|| current_user_can('manage_woocommerce'); // admin / support staff

}

// Guest orders should rely on WooCommerce's order key mechanism

$key_param = $_GET['key'] ?? null;

return $key_param && hash_equals($order->get_order_key(), $key_param);

}

In practice, the plugin’s 1.0.9 fix leans on WooCommerce’s existing mechanisms for guest order validation and adds proper authorization checks around wa_order_thank_you_override.(wiz.io)

The real lesson is not that one function was missing a condition, but that authorization logic was scattered instead of being consistently enforced at the object level.

Why IDOR Keeps Showing Up (Especially in the API and AI Era)

If you read through modern analyses of IDOR/BOLA—whether from OWASP, apisecurity.io, escape.tech, or Traceable—you’ll see the same pattern repeated.(OWASP)

A few structural reasons:

- APIs and SPAs expose IDs by design Front-ends, mobile apps, and third-party integrations all need stable identifiers. It’s natural to see

/orders/12345or{"order_id":12345}in the wild. - Authorization is treated as a “bolt-on” Teams often think in terms of “logged-in vs guest,” and forget that two different logged-in users still need different access to the same endpoint. BOLA is not about authentication; it’s about whether this caller can access that specific object.

- Logic is scattered across controllers and handlers Instead of a central

canAccess(order, user)enforced for every access path, each handler rolls its own partial checks. Sooner or later, one path forgets. - Testing is biased toward “happy paths” QA and even some pentest engagements still focus on “user A does A-things, user B does B-things,” not “user A tries to access B’s objects by guessing IDs.”

- Automation tends to be endpoint-centric, not object-centric Many scanners treat each URL as a separate asset, but BOLA is about relationships: same endpoint, different identities, different objects.

The result is a steady stream of CVEs—CVE-2025-13526 included—where the exploit boils down to “take your own URL, change a number, get somebody else’s data.”

Practical Strategies: Finding and Fixing IDOR Before It Becomes a CVE

For engineering and security teams, the question is not “Is IDOR bad?”—we all agree it is. The real question is how to systematically reduce the chance of shipping one, and how to detect it when you inevitably miss something.

1. Design for Object-Level Authorization Explicitly

At the code and architecture level:

- Treat “who can access this object?” as a first-class question in your domain model.

- Implement central functions like

canViewOrder(order, user)orisAccountMember(account, user)and call them everywhere an object is read or mutated. - Avoid duplicating authorization logic across controllers, views, and utility helpers.

2. Make Broken Object-Level Authorization Part of Your Threat Model

When you design or review a feature:

- Identify all objects exposed via IDs (orders, carts, chats, tickets, documents).

- Enumerate all code paths that read or write those objects.

- For each path, ask explicitly: “If I change this ID, what stops me from seeing someone else’s data?”

OWASP’s API1:2023 guidance and CWE-639’s taxonomy are useful anchors here.(OWASP)

3. Test Like an Attacker: Multi-User, Multi-Session, Same Endpoint

In manual testing:

- Use at least two normal user accounts (A and B), plus a “no-auth” session.

- For each endpoint that references an ID in the path, query, body, or header, send A’s IDs from B’s session and vice versa.

- Look for subtle differences in HTTP status codes, response sizes, and body content.

In automated testing, you want tooling that can:

- Learn the schema of your identifiers (e.g.,

order_id,messageId, UUIDs). - Replay recorded traffic with mutated IDs under different session contexts.

- Flag cases where data leaks across tenant or user boundaries.

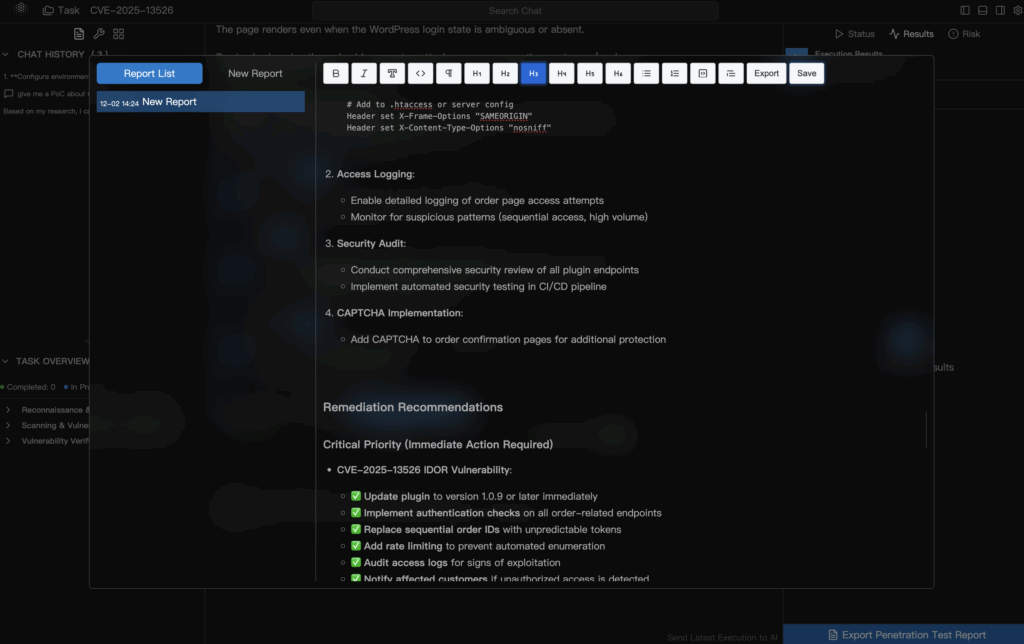

Where AI Fits: Using Penligent to Scale IDOR Discovery and Validation

IDOR and CVE-2025-13526 are also a good lens for thinking about AI-assisted security testing.

Modern applications are messy:

- Multiple front-ends (web, mobile, internal tooling).

- A mix of REST, GraphQL, WebSocket, and RPC endpoints.

- Complex identity models (users, tenants, organizations, “workspaces”).

Trying to manually reason about every possible ID and every possible access path is exactly the sort of work you want machines to help with.

That’s where platforms like Penligent come in.

From Recorded Traffic to IDOR Hypotheses

Penligent is built as an AI-powered pentest platform that can:

- Ingest API descriptions and live traffic

- Pull OpenAPI/Swagger specs, Postman collections, or proxy captures.

- Use LLM-based analysis to identify likely object identifiers (

order_id,user_id,chat_id, etc.) and map them to resources.

- Generate IDOR test plans automatically

- For each candidate endpoint, synthesize test cases where:

- User A’s IDs are replayed under user B’s session.

- Guest sessions replay IDs from authenticated sessions.

- Look for differences in responses that indicate unauthorized data access.

- For each candidate endpoint, synthesize test cases where:

- Validate and document real impact

- When a suspected IDOR behaves like CVE-2025-13526—returning other users’ order data—Penligent can:

- Capture the exact requests and responses as evidence.

- Extract the sensitive fields exposed (names, emails, addresses).

- Generate a developer-friendly report that ties the behavior back to the specific handler or controller.

- When a suspected IDOR behaves like CVE-2025-13526—returning other users’ order data—Penligent can:

Instead of security engineers hand-crafting every test, they can focus on reviewing hypotheses, prioritizing findings, and working with developers on durable fixes.

From CVE-2025-13526 to “Could This Happen in Our Stack?”

CVE-2025-13526 is a WordPress plugin bug, but the pattern applies equally to:

- SaaS dashboards (“/api/v1/reports/{reportId}”).

- Internal admin tools (“/tickets/{id}/details”).

- Machine-to-machine APIs in microservices.

A Penligent-style workflow lets you ask a higher-value question:

“Show me everywhere in our stack where something behaves like CVE-2025-13526.”

You are no longer limited to waiting for public CVEs. You get an internal, continuously updated map of potential IDORs—with proof, not just speculation.

Takeaways for Security and AI Engineering Teams

CVE-2025-13526 is a neat headline for this week’s vulnerability feeds, but the deeper lessons are longer-lived:

- IDOR is an architecture smell, not just a missing

ifIf authorization logic is scattered and optional, you will eventually ship a CVE-2025-13526 of your own, whether in WordPress, Python, Go, or Rust. - BOLA should be treated as a “design bug,” not an edge case OWASP’s API1 is at the top of the list for a reason: it’s easy to miss and devastating when it leaks PII across tenants.(OWASP)

- Automated testing must be object-aware, not just endpoint-aware It’s not enough to hit each URL once. Real IDOR testing means replaying the same URL under different identities with different object IDs.

- AI can and should help Platforms like Penligent can shoulder the repetitive work of generating test cases, mutating IDs, and diffing responses, so human engineers can spend time modeling risk and crafting defenses instead of manually tweaking

order_idin a browser.

If you build or secure systems that expose user data—and especially if you’re experimenting with AI-driven automation in your security workflows—CVE-2025-13526 is more than another WordPress headline. It’s a reminder that IDOR is the kind of vulnerability where AI plus human expertise can meaningfully move the needle, turning automated parameter tampering into a deliberate, explainable, and repeatable part of your security engineering practice.