If you’ve noticed “bleeping computer” popping up in search bars, Slack threads, or ticket comments, it’s rarely because someone is confused about a noisy laptop. Most of the time it’s a shortcut: people are trying to get to BleepingComputer quickly without typing a domain, and they want one of two things right now:

- a Patch Tuesday summary they can actually act on, or

- a concrete, testable explanation of a vulnerability chain that’s easy to brief and verify.

That dynamic became especially visible in February 2026, when BleepingComputer published a widely-circulated Patch Tuesday roundup stating Microsoft fixed 58 vulnerabilities, including six actively exploited そして three publicly disclosed zero-day issues. (ブリーピングコンピューター) In the same news cycle, the site also covered CVE-2026-20841, a Windows 11 Notepad (Store app) Markdown-link remote code execution issue where crafted links could trigger unverified protocol launches when a user clicks/ctrl-clicks a malicious Markdown link. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

The result: the brand keyword (“bleeping computer”) acts as the fastest “get me the source” query for busy defenders.

What people really mean when they search “bleeping computer”

Search intent for this keyword is unusually pragmatic. It’s not “learn cybersecurity.” It’s “I need the specific artifact I remember reading.”

A good way to validate that is to look at traffic and keyword patterns. Similarweb lists “bleeping computer” as the top organic keyword driving visits to BleepingComputer (a classic brand-query behavior), with adjacent high-volume terms tied to practical IR tooling and troubleshooting. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

At the same time, BleepingComputer positions itself as both a news destination and a long-running community with guides, forums, and self-help resources—so the keyword becomes sticky even outside of big headlines. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

In practice, “bleeping computer” searchers usually want one of these outcomes:

- A Patch Tuesday / zero-day brief they can paste into an internal advisory, change request, or risk update. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

- A single CVE explanation with enough detail to test a hypothesis (versions, trigger conditions, user interaction, blast radius). (NVD)

- A tool or guide during triage (downloads, cleanup steps, incident troubleshooting). (ブリーピングコンピューター)

So the real question isn’t “why are people searching it?” The question is: how do we turn that behavior into something repeatable, measurable, and less chaotic?

The February 2026 catalyst: Patch Tuesday + Notepad + “one click becomes execution”

Patch Tuesday with “actively exploited” changes the operational tempo

The February 10, 2026 Patch Tuesday roundup reported 58 flaws fixed, including six actively exploited zero-days. (ブリーピングコンピューター) That single phrase—“actively exploited”—is what pushes a story from “read later” to “triage now.”

It’s also why this kind of roundup spreads: it gives an org-wide coordination point that security, IT, endpoint, and platform teams can all reference.

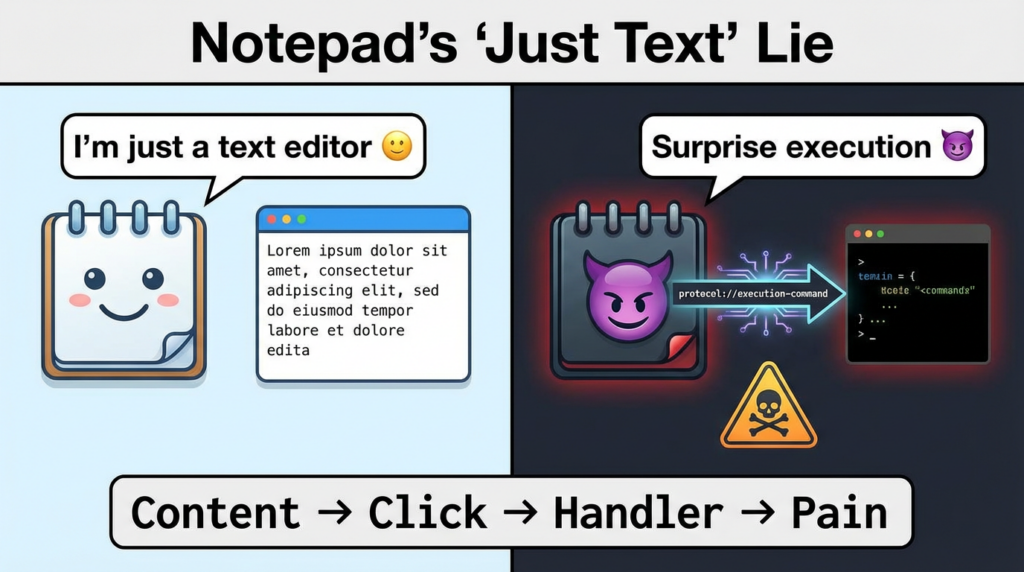

CVE-2026-20841: Notepad + Markdown links becomes a trust-boundary story

The Notepad Markdown vulnerability caught attention because it compresses modern endpoint risk into a familiar object: a text editor. NVD describes CVE-2026-20841 as improper neutralization of special elements used in a command (CWE-77), with a CVSS v3.1 base vector AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:R/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H. (NVD)

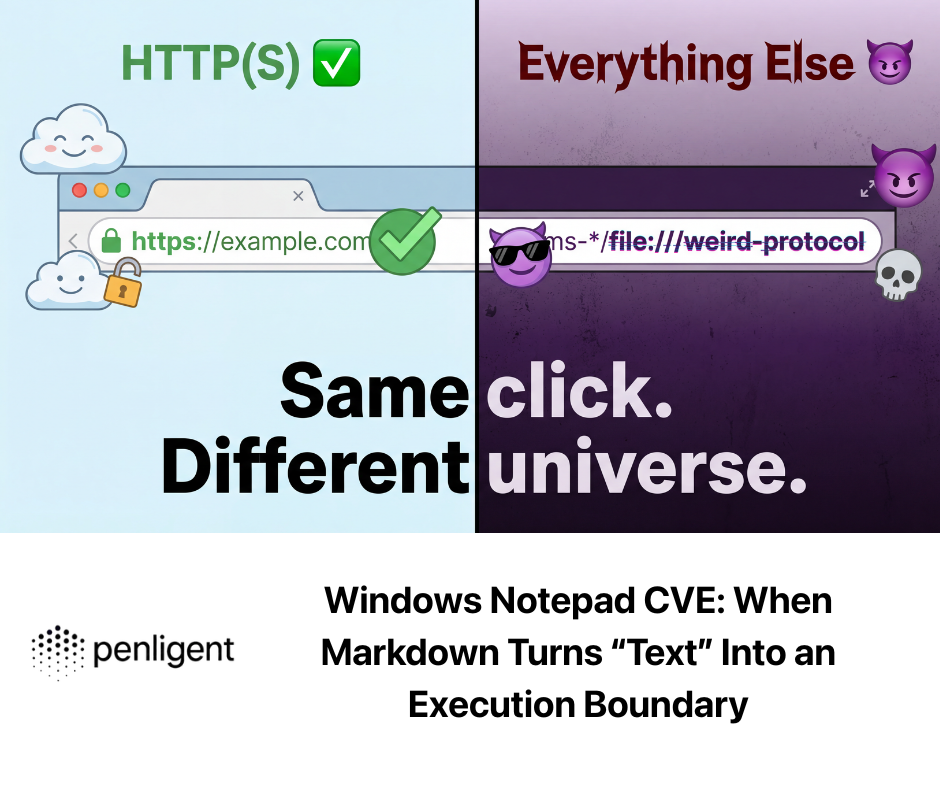

BleepingComputer’s coverage explains the practical chain: a user can be tricked into clicking a malicious link in a Markdown file opened in Notepad, causing the application to launch unverified protocols that load/execute remote files. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

This is why it travels: it’s not a theoretical exploit class. It’s a familiar user action (click) becoming an execution primitive.

CVE-2026-21510: “security prompt boundaries” are not a control

In the same Patch Tuesday story, one of the highlighted exploited issues is CVE-2026-21510, a Windows Shell “protection mechanism failure” that CISA added to the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog on February 10, 2026. (NVD)

Even if your environment is “good at patching,” the lesson from issues like CVE-2026-21510 is consistent: don’t rely on warnings, prompts, or user friction as a security boundary. You need policy controls and telemetry that still work when the UI doesn’t.

Treat these as a family: “content,click,protocol handler ,execution”

If you only track CVEs one by one, you’ll keep re-learning the same story:

- untrusted content lands (email, chat, repo, ticket, file share),

- an app renders it,

- the user performs a normal action,

- the OS dispatches a handler (shell/protocol/installer/script host),

- you end up with an execution path that looks “normal enough” to slip past casual scrutiny.

CVE-2026-20841 is a clean example of that family. (NVD)

CVE-2026-21510 is another angle: a protection mechanism failure in the shell boundary. (NVD)

A durable defense strategy focuses on the invariant chain, not the label:

- Reduce risky handlers and install surfaces (least privilege, app control).

- Detect odd parent/child process and protocol invocations.

- Prove remediation with version evidence + regression tests (not “we patched”).

A practical playbook: turn “bleeping computer” into an intake pipeline

Step 1: RSS ingestion (low-cost, high-signal)

BleepingComputer publishes RSS feeds you can ingest without scraping pages. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

Here’s a minimal RSS triage script that scores items by (a) operational keywords and (b) CVE mentions:

import re

import feedparser

FEED_URL = "<https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/feed/>"

CVE_RE = re.compile(r"\\bCVE-\\d{4}-\\d{4,7}\\b", re.IGNORECASE)

keywords = [

"Patch Tuesday", "actively exploited", "zero-day",

"Notepad", "Markdown", "SmartScreen", "Windows Shell",

"remote code execution", "security feature bypass"

]

feed = feedparser.parse(FEED_URL)

def score(title: str, summary: str) -> int:

text = f"{title}\\n{summary}".lower()

s = sum(1 for k in keywords if k.lower() in text)

s += 2 * len(set(CVE_RE.findall(text)))

return s

ranked = []

for e in feed.entries[:100]:

title = e.get("title", "")

summary = e.get("summary", "")

link = e.get("link", "")

ranked.append((score(title, summary), title, link))

for s, title, link in sorted(ranked, reverse=True)[:20]:

print(f"[{s:02d}] {title}\\n{link}\\n")

What you do with this output matters more than the code. The win is turning “someone saw an article” into “a structured intake object.”

Step 2: Enrich with CVE truth sources (NVD + CISA)

For CVE facts, prefer authoritative records:

- NVD for CVSS/CWE/official references. (NVD)

- CISA KEV to confirm exploitation status and remediation deadlines (where applicable). (CISA)

例えば、こうだ:

- CVE-2026-20841 (Notepad App): CVSS vector and CWE are on NVD; MSRC is referenced from NVD. (NVD)

- CVE-2026-21510 (Windows Shell): NVD explicitly flags KEV inclusion, and CISA’s KEV catalog lists the required action. (NVD)

Step 3: Convert into a “one-page decision memo”

This is what most teams actually need during a hot week:

| フィールド | What you fill in | Example based on Feb 2026 items |

|---|---|---|

| トリガー | Why you care now | “Actively exploited” zero-days in Patch Tuesday (ブリーピングコンピューター) |

| スコープ | Which assets are exposed | Win11 endpoints with Store Notepad; any endpoints in KEV scope |

| Exploit chain | One-sentence story | “Markdown link in Notepad can invoke unverified protocols” (ブリーピングコンピューター) |

| 優先順位 | What gets patched first | Internet-facing, high-privilege, exec endpoints |

| Proof | How you confirm remediated | version inventory + regression test cases |

| 検出 | What you watch for anyway | suspicious handler launches; odd parent-child trees |

Detection content you can ship without playing “write a SIEM novel”

You don’t need to overfit to one CVE. You want signals that survive the next variant.

Microsoft Defender / KQL idea: Notepad spawning suspicious children

This is a pattern query—not a PoC.

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(7d)

| where FileName in~ ("notepad.exe", "notepad++.exe") // include alternatives if you want

| where InitiatingProcessFileName has_any ("notepad", "notepad.exe")

| where ProcessCommandLine has_any ("ms-appinstaller:", "file://", "powershell", "cmd.exe", "wscript", "cscript")

or FileName in~ ("powershell.exe","cmd.exe","wscript.exe","cscript.exe","msiexec.exe","rundll32.exe")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine,

FileName, ProcessCommandLine, AccountName, SHA256

| order by Timestamp desc

Tuning notes:

- Focus on parent/child そして protocol/handler strings.

- Add allowlists for known internal toolchains.

- Pair with user interaction telemetry if you have it.

Sigma-style idea: suspicious protocol handlers launched after opening Markdown

title: Suspicious protocol handler launch from Notepad context

logsource:

product: windows

category: process_creation

detection:

selection_parent:

ParentImage|endswith:

- '\\notepad.exe'

selection_child:

CommandLine|contains:

- 'ms-appinstaller:'

- 'file://'

- 'powershell'

- 'cmd.exe'

condition: selection_parent and selection_child

falsepositives:

- Legitimate installer workflows triggered by IT scripts

level: high

These are starting points. The point is to capture the chain, not the CVE label.

What to do about CVE-2026-20841 and CVE-2026-21510 in real environments

For CVE-2026-20841 (Notepad App)

- Patch: prioritize the Notepad Store app updates that address the issue; NVD provides the authoritative CVE record and references MSRC. (NVD)

- Reduce handler risk: if your org allows it, restrict high-risk protocol handlers and installer flows on endpoints that don’t need them.

- Regression test: keep a small set of benign “handler invocation” test files in a controlled lab to confirm the environment behaves the way you think after updates.

For CVE-2026-21510 (Windows Shell, KEV)

- Treat KEV as a clock: the NVD record highlights KEV inclusion and CISA lists required actions; if you’re in a regulated environment, that’s not optional. (NVD)

- Assume social engineering will happen: even when user interaction is required, exploitation at scale relies on repeated attempts.

- Add durable telemetry: shell-related bypasses are exactly why you want detection on unusual link/shortcut execution flows.

A short “don’t get fooled by the keyword” takeaway

When “bleeping computer” trends, it’s a signal that defenders are doing what they always do under pressure: they reach for sources that compress chaos into operationally useful summaries. In February 2026, that compression happened around Patch Tuesday’s exploited zero-days and a high-impact endpoint trust-boundary issue in Notepad. (ブリーピングコンピューター)

Your advantage comes from not treating this as news consumption. Treat it as input data and build a workflow that outputs:

- prioritized remediation,

- measurable fleet status,

- and detections that outlive the headline.