Why this CVE shows up in real pipelines more than people expect

When engineers search for “cve-2025-4517 poc”, they’re rarely looking for a party trick. They’re trying to answer a very specific operational question:

“If someone hands my automation a tarball, can it make my process write files outside the directory I thought was safe?”

That is exactly the class of bug CVE-2025-4517 represents: an extraction-boundary failure in Python’s standard library tarfile module when extracting untrusted tar archives with TarFile.extractall() 또는 TarFile.extract() using the filter= parameter set to "data" 또는 "tar". The NVD record is explicit about the affected condition and version range: Python 3.12 or later are affected, because earlier versions do not include the extraction filter feature. (NVD)

If you’ve been around long enough, you’ll recognize the family resemblance: this is the “Zip Slip” idea applied to tar semantics, with modern twists like symlinks 그리고 realpath behavior. But the reason this one keeps appearing in serious conversations is not because it’s exotic. It’s because tar extraction is everywhere:

- CI/CD jobs fetching and unpacking source artifacts

- internal build tools that unpack plugin bundles

- ML workflows unpacking datasets, model weights, or cached artifacts

- dependency tools handling sdists and tar-based distributions

- “agentic” automation that downloads, unpacks, and processes archives at speed

The security failure mode isn’t complicated: you thought “extracting to /tmp/job-123/” meant the archive contents could only land inside that directory. CVE-2025-4517 is about breaking that assumption under certain extraction patterns. (NVD)

What people actually click in SERPs for this CVE

You asked for “the highest-click-through terms on the web” and to read and synthesize viewpoints. We can’t see Google Search Console CTR numbers from here, but we can reliably infer the phrasing that dominates high-signal coverage and repeats across vendor databases and advisories. In practice, the titles and snippets that most often win clicks for engineers cluster around these patterns:

- “Python tarfile path traversal” (clear class name, instantly scannable) (SentinelOne)

- “arbitrary file write” (high-severity wording, immediately communicates impact) (Red Hat Customer Portal)

- “TarFile.extractall filter=data/tar” (precise trigger; engineers click because it matches their code) (NVD)

- “supply chain risk / CI/CD” (why it matters beyond a local script) (Linux Security)

- “mitigation / safe extraction / how to check” (actionable, operational intent) (Gist)

Those phrases map cleanly to user intent. Most readers don’t want drama. They want a proof they can run safely, then a remediation plan that doesn’t break pipelines.

This article is written to match that intent: defensive validation, exposure triage, mitigation및 monitoring, without turning into an exploit drop.

Ground truth: what CVE-2025-4517 is and what it is not

What it is:

A vulnerability in CPython’s tarfile module where extracting an untrusted tar archive using TarFile.extractall() 또는 TarFile.extract() 와 함께 filter="data" 또는 filter="tar" can allow archive members to result in filesystem actions outside the intended destination directory (i.e., beyond the extraction boundary). The NVD summary and affected-condition text are the canonical baseline. (NVD)

Red Hat’s CVE entry characterizes the issue in the same practical terms: a flaw in CPython tarfile allowing writes outside the extraction directory when extracting untrusted archives. (Red Hat Customer Portal)

Google’s security advisory (GHSA) for a tarfile realpath-related issue describes the tested impact as allowing file reads and writes outside the destination path on Linux and macOS—consistent with the same extraction-boundary failure class engineers care about. (GitHub)

What it is not:

- It is not automatically “remote code execution” by itself.

- It does not magically grant privileges you don’t already have.

- The impact is bounded by the permissions of the process doing the extraction.

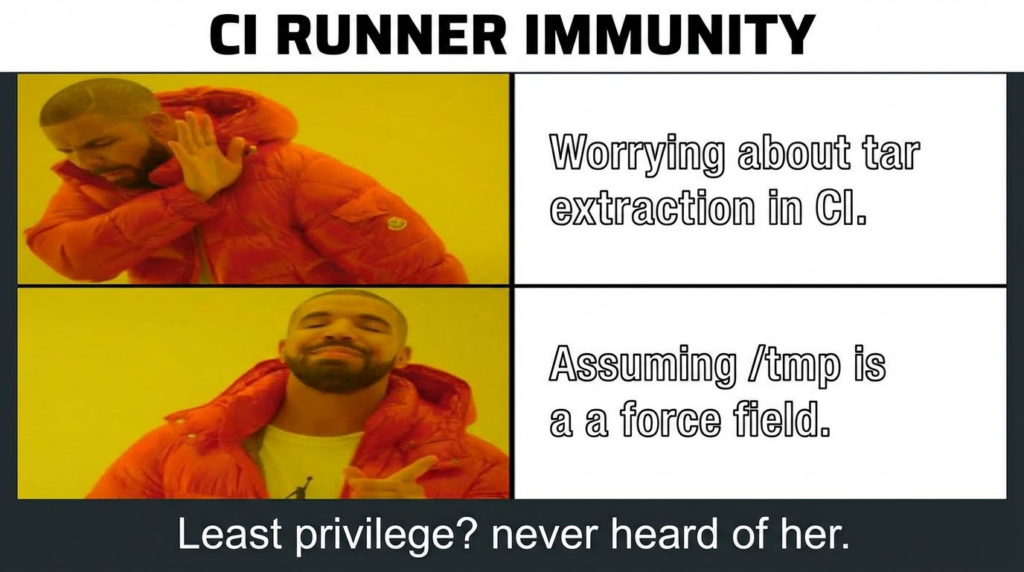

But that “bounded by process permissions” line is exactly why it matters: your CI runner often has write permissions to places you really don’t want an attacker controlling.

The practical risk model: how boundary breaks become real incidents

Think in terms of what an attacker can do if they can cause controlled writes outside your extraction directory, as the same user your job is running under.

Here are realistic outcomes that do not require fantasy privileges:

- Configuration poisoning Overwriting config files that your pipeline reads later in the same job. This can redirect outputs, alter build flags, or change “where artifacts are published.”

- Workspace contamination Writing into your repo workspace or build cache to influence what gets built or tested.

- Credential or token targeting Dropping files in locations that get automatically read, uploaded, or cached.

- Persistence inside long-lived runners On shared or misconfigured runners, file writes can plant state that impacts subsequent jobs.

You don’t need to imagine a single-click RCE chain. In supply chain security, small primitives compose.

This is also why some vulnerability databases mention the supply-chain angle explicitly: tar archives are a packaging and distribution primitive, and many automation systems unpack them routinely. (Linux Security)

The defensive PoC philosophy: prove exposure, don’t publish a weapon

You asked for a PoC. Here’s the line we’ll hold:

- We will build a benign archive that attempts to write a harmless marker file outside the destination directory using traversal-like member names.

- We will extract into a temporary directory under a controlled test root.

- We will only check whether a file ends up outside the intended directory—no payloads, no persistence locations, no sensitive paths, no bypass tricks.

That gives defenders what they need: a reproducible “yes/no” proof.

Defensive PoC: safe boundary-break validation script

What this does

- Creates a test root like

./cve_2025_4517_lab/ - Creates an extraction destination

./cve_2025_4517_lab/dest/ - Creates a tarball containing a member name that attempts to escape into

./cve_2025_4517_lab/escaped/ - Runs

tarfile.extractall(..., filter="data")and checks whether the marker appears outsidedest/

Note: The NVD record specifically calls out extraction with

filter="data"또는filter="tar"as the affected condition. (NVD)

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Defensive validation for CVE-2025-4517-style extraction boundary failures.

Goal:

- Safely test whether tar extraction can write outside the intended destination directory

under the affected extraction patterns (extractall/extract + filter="data"/"tar").

This script:

- Uses a local lab directory only

- Writes a harmless marker file

- Avoids sensitive paths and any weaponization

"""

import os

import tarfile

from pathlib import Path

LAB = Path("cve_2025_4517_lab").resolve()

DEST = LAB / "dest"

ESCAPED = LAB / "escaped"

TAR_PATH = LAB / "test.tar"

MARKER_NAME = "../escaped/marker.txt" # boundary escape attempt

MARKER_CONTENT = b"boundary-check\\n"

def reset_lab():

for p in [DEST, ESCAPED]:

p.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

if TAR_PATH.exists():

TAR_PATH.unlink()

marker = ESCAPED / "marker.txt"

if marker.exists():

marker.unlink()

def build_tar():

# Build a tar with a traversal-like member name that tries to escape DEST into ESCAPED

with tarfile.open(TAR_PATH, "w") as tf:

ti = tarfile.TarInfo(name=MARKER_NAME)

ti.size = len(MARKER_CONTENT)

# Keep permissions boring

ti.mode = 0o644

tf.addfile(ti, fileobj=io.BytesIO(MARKER_CONTENT))

def extract_with_filter(filter_value: str):

# Extract into DEST with a specified filter

with tarfile.open(TAR_PATH, "r") as tf:

tf.extractall(path=DEST, filter=filter_value)

def check_result():

escaped_marker = ESCAPED / "marker.txt"

in_dest = DEST / "marker.txt"

return escaped_marker.exists(), in_dest.exists(), escaped_marker

if __name__ == "__main__":

import io

reset_lab()

build_tar()

results = {}

for f in ["data", "tar"]:

try:

reset_lab()

build_tar()

extract_with_filter(f)

escaped, in_dest, escaped_path = check_result()

results[f] = {"escaped": escaped, "in_dest": in_dest, "escaped_path": str(escaped_path)}

except Exception as e:

results[f] = {"error": repr(e)}

print("Lab root:", LAB)

print("Results:")

for k, v in results.items():

print(f" filter={k}: {v}")

How to interpret outputs

- 만약

escaped=True, you have direct evidence that the extraction boundary failed for that filter mode under your environment. - If an exception is raised, that may still be “good news” depending on the nature of the exception—some mitigations intentionally hard-fail on unsafe members.

This is the minimal “proof of risk” that satisfies most security reviews: a controlled file-write outside the intended directory.

Find it in your codebase: what to grep and what to review

Most teams discover exposure because an engineer greps their build tooling and finds tar extraction sprinkled everywhere. Start with this:

# Direct tarfile usage

rg -n "import\\s+tarfile|tarfile\\.open\\(|extractall\\(|extract\\(" .

# Focus on the affected trigger patterns called out by NVD

rg -n "extractall\\([^)]*filter\\s*=\\s*[\\"'](data|tar)[\\"']" .

rg -n "extract\\([^)]*filter\\s*=\\s*[\\"'](data|tar)[\\"']" .

Then classify each finding into one of these buckets:

| Bucket | Typical location | Risk level | What to do |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untrusted input | CI artifact downloads, plugin bundles, “import dataset”, agent downloads | 높음 | Replace with safe extraction wrapper + sandbox/least privilege |

| Trusted internal artifacts | build outputs signed/attested, internal release system | Medium | Add signature/attestation checks + still use safe extraction |

| Local dev utilities | scripts run by engineers manually | 낮음-중간 | Still patch, but prioritize CI paths first |

This is the “why engineers click ‘how to check if vulnerable’” part: the real risk is almost always in automation.

Mitigation: what actually fixes the class of bug

NVD’s record points engineers toward the tarfile extraction filter documentation and clarifies the affected condition. (NVD)

In practice, you want layered mitigation:

- Upgrade Python / consume distro patches Track remediation via your platform vendor (e.g., Red Hat) or your base images. Red Hat’s CVE page is a common anchor for enterprise patch status. (Red Hat Customer Portal) Also expect scanners (e.g., Tenable/Nessus) to flag patched packages at the distro layer. (Tenable®)

- Never extract untrusted tarballs with raw

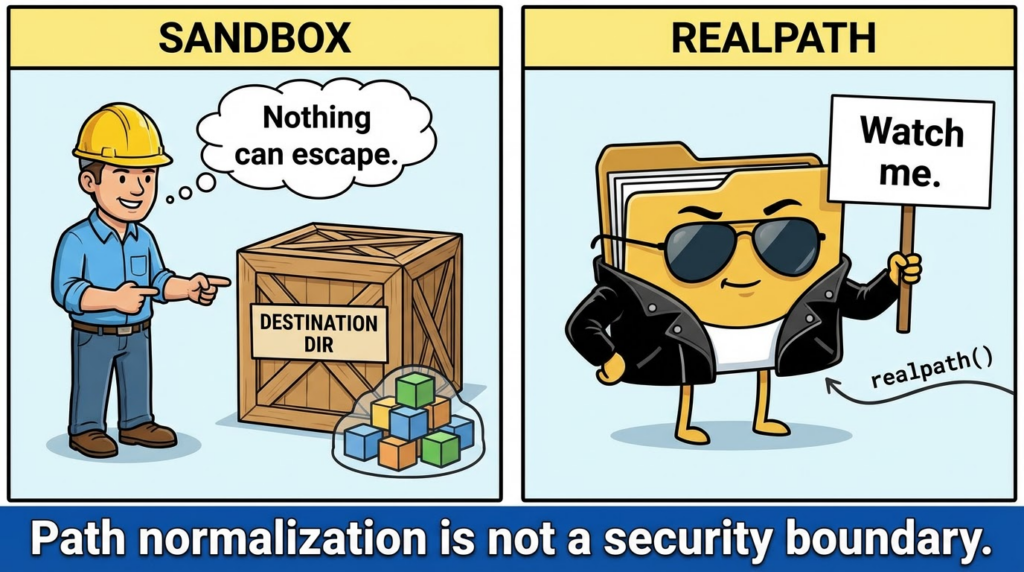

extractallEven if patched, archive extraction is a historically sharp edge. Make “safe extraction” a policy, not a one-off fix. - Use a safe extraction wrapper that enforces a realpath prefix check If you can’t upgrade immediately, this is your “band-aid that actually works.”

Here is a hardened extraction approach you can drop into automation. It denies members whose final resolved path escapes the destination:

from __future__ import annotations

import os

import tarfile

from pathlib import Path

class UnsafeTarMember(Exception):

pass

def safe_extract_tar(tf: tarfile.TarFile, dest: str | os.PathLike) -> None:

dest_path = Path(dest).resolve()

for member in tf.getmembers():

member_name = member.name

# Reject absolute paths early

if Path(member_name).is_absolute():

raise UnsafeTarMember(f"absolute path not allowed: {member_name}")

target_path = (dest_path / member_name).resolve()

# Enforce that the extracted path stays under dest_path

if not str(target_path).startswith(str(dest_path) + os.sep):

raise UnsafeTarMember(f"path escape attempt: {member_name} -> {target_path}")

# Optional: tighten on symlinks/hardlinks depending on your threat model

if member.issym() or member.islnk():

# Many real-world archive exploits rely on link tricks

raise UnsafeTarMember(f"links not allowed: {member_name}")

# If everything passes, extract

tf.extractall(path=dest_path)

You’ll notice we also block symlinks/hardlinks by default. That’s opinionated, but it matches how teams treat untrusted archives in CI. If you need links for legitimate use, you can allow them after additional checks, but do it consciously.

- Run extraction with least privilege Even a “file write outside dest” is much less scary if the process can’t write anywhere sensitive.

Monitoring: how to catch the bad outcomes you actually care about

A lot of security guidance stops at “upgrade and move on.” But in large orgs, you’ll want detection too—because the most realistic failure is “someone forgot one pipeline.”

모니터링 대상

- Unexpected file writes outside designated working directories during build or import steps

- Extraction errors that indicate blocked unsafe members (these become a signal of probing)

- Creation of files in “should never change during build” locations

Here’s a simple operational pattern:

- Define an allowlist of writable roots for CI jobs:

workspace/,tmp/,cache/ - Alert on writes outside these during steps that perform extraction

Minimal SIEM field mapping table

| Telemetry source | Useful fields | What to flag |

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint process/file events | process name, command line, file path, parent process | Python process writing outside workspace shortly after reading a .tar |

| CI job logs | step name, artifact URL, extraction path, error text | “blocked member”, “path escape”, unexpected files created |

| Container runtime logs | mount points, writes to mounted volumes | Writes to mounted secrets/config volumes during extract steps |

This kind of detection gives you confidence you’re not just “patched,” but actually safe in practice.

Related CVEs and why you should treat archives as an attack surface

Archive parsing vulnerabilities are a repeating story. Even when the exact bug differs, the pattern is stable:

- “The archive member name isn’t just a name; it’s a filesystem operation.”

- “Links and path normalization can turn a safe-looking extraction into a write-where-you-want primitive.”

If your security program already has a “Zip Slip” mental model, CVE-2025-4517 is the tarfile version of the same lesson, made more relevant by modern automation.

For additional context on archive and extraction issues as a broad theme, the Alpha-Omega archive security paper discusses multiple archive-related vulnerabilities and patterns across ecosystems. (Alpha Omega)

If you treat CVE-2025-4517 as a pipeline risk rather than a one-off bug, the hard part becomes: “How do I prove I’m not exposed across dozens of repos and runners?”

That’s a workflow problem, not just a patch problem.

펜리전트 can plug into this kind of work in two non-forced ways:

First, during exposure triage, you can use an AI-assisted security workflow to inventory and prioritize where archive extraction happens in your automation—especially the code paths that match the NVD trigger pattern (extractall/extract 와 함께 filter="data" 또는 "tar"). The goal isn’t a vague “AI scan,” but a concrete set of findings you can hand to platform owners: where extraction occurs, what input trust boundary it assumes, and what privilege context it runs under.

Second, during defensive validation, you can standardize safe test harnesses like the boundary-check PoC above and run them against staging environments. Evidence-first reporting matters here: security reviews move faster when you can show “here is the file that landed outside the intended directory,” instead of arguing about hypotheticals.

Checklist you can hand to an on-call platform engineer

- Identify Python 3.12+ usage in CI images and runners (start with base images and lockfiles). (NVD)

- 찾기

tarfileextraction call sites, especiallyextractall/extract와 함께filter="data"또는"tar". (NVD) - Run the defensive boundary-check PoC in a lab environment that mirrors CI.

- Patch/upgrade via vendor channels where possible (track distro advisories). (Red Hat Customer Portal)

- Add a safe extraction wrapper and deny links for untrusted archives.

- Enforce least privilege and restrict writable directories in CI.

- Add monitoring for out-of-workspace writes during extraction steps.

That sequence is what most teams actually do when they take this seriously.

참조

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2025-4517-poc-without-weaponizing-it-defensive-validation-patch-lines-and-the-tarfile-trap-inside-automation/ (펜리전트)

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/virustotal-in-incident-response-how-to-identify-malware-fast-and-pivot-without-leaking-data/ (펜리전트)

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-2441-the-chrome-css-zero-day-that-starts-inside-the-sandbox-and-rarely-ends-there/ (펜리전트)

https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-4517 (NVD)

https://access.redhat.com/security/cve/cve-2025-4517 (Red Hat Customer Portal)

https://docs.python.org/3/library/tarfile.html#tarfile-extraction-filter (NVD)

https://github.com/google/security-research/security/advisories/GHSA-hgqp-3mmf-7h8f (GitHub)

https://gist.github.com/sethmlarson/52398e33eff261329a0180ac1d54f42f (Gist)

https://www.sentinelone.com/vulnerability-database/cve-2025-4517/ (SentinelOne)