Why this CVE suddenly mattered to people who don’t even “do Python security”

CVE-2025-4517 didn’t go viral because it’s exotic. It moved because it targets a habit: “Download → unpack → continue”.

That habit shows up everywhere now:

- CI/CD runners unpack artifacts pulled from registries and build caches.

- ML pipelines unpack model bundles and datasets.

- Plugin ecosystems unpack extensions.

- Internal automation unpacks “data” tarballs because tar is convenient.

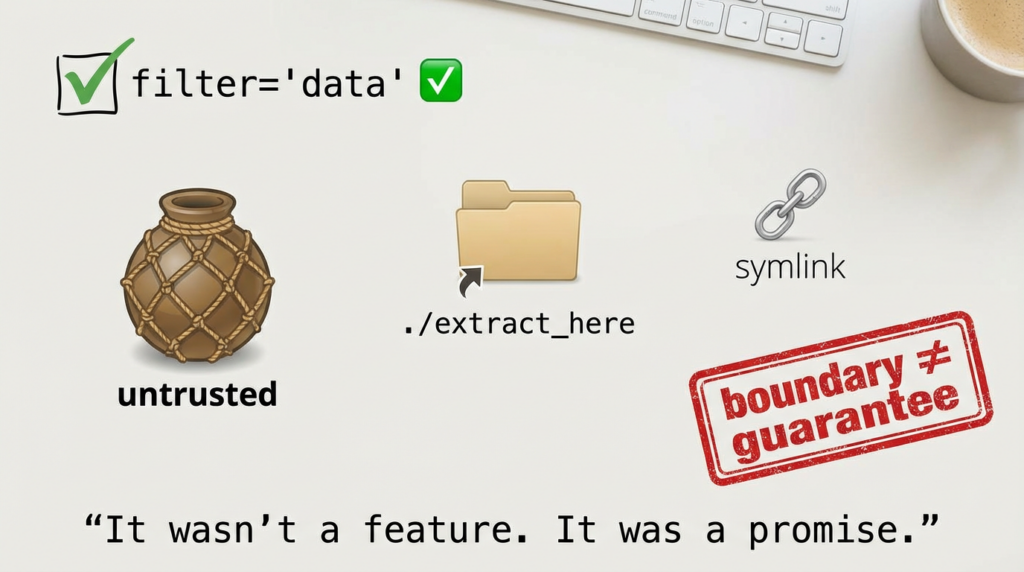

The official description is unusually explicit about the dangerous path: you’re affected if you use Python’s tarfile module to extract untrusted tar archives مع TarFile.extractall() أو TarFile.extract() و the filter= parameter is "data" أو "tar". It also clarifies scope: only Python 3.12+ is in play, because earlier versions don’t include the extraction filter feature. (NVD)

That combination—standard library + common workflow + low-friction exploitation primitives (write outside destination)—is exactly what makes security engineers search “CVE-2025-4517 PoC” at 2AM.

What CVE-2025-4517 is, precisely

At a practical level, this is a write-outside-extraction-directory primitive triggered during tar extraction under specific conditions.

- المكوّن: Python standard library

tarfile - الزناد Extracting untrusted tar archives using

TarFile.extractall()أوTarFile.extract()معfilter="data"أوfilter="tar" - التأثير: archive members can cause file reads/writes outside the destination directory (i.e., beyond the extraction boundary)

- Affected: Python 3.12+ (per NVD)

- Severity: CVSS 9.4 on NVD (critical)

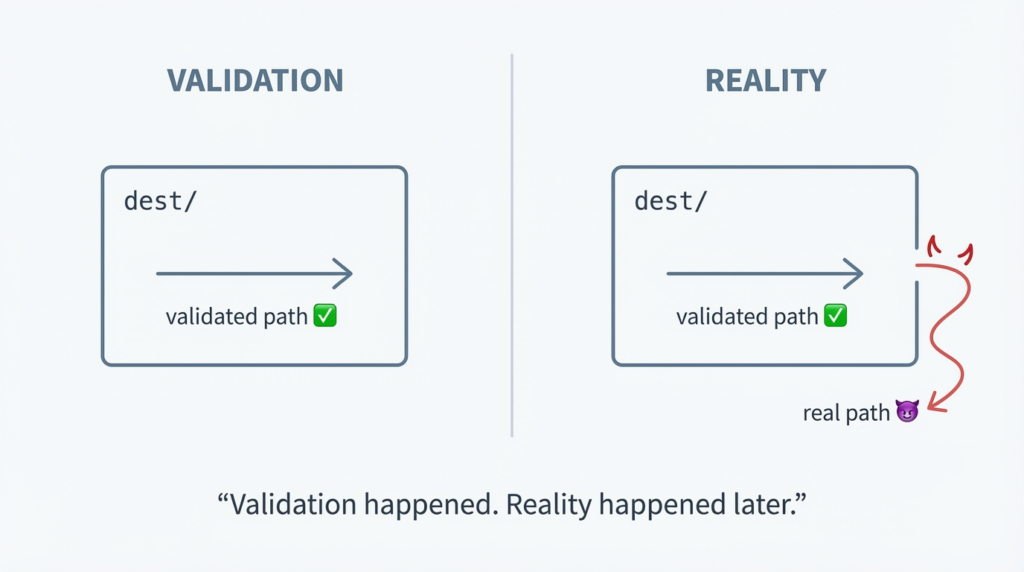

The high-signal technical writeup from Google’s security research advisory frames the underlying failure as a mismatch between path validation و path realization (involving os.path.realpath() behavior and PATH_MAX constraints), which allows arbitrary reads/writes outside the destination path in tested scenarios. (جيثب)

If you want a single sentence for internal comms:

“This is what happens when ‘safe extraction filters’ become a false sense of safety in automated pipelines.”

What the top-ranking writeups tend to emphasize

You asked for “highest-CTR words / angles” and to absorb them. We can’t directly measure CTR from outside the search engines, but we يمكن observe what consistently ranks and what those pages lead with. Across NVD + major vendor databases + security writeups, the recurring, click-driving terms are:

- critical / CVSS 9.x

- arbitrary file write / write outside extraction directory

- untrusted tar archives

- supply chain / CI/CD automation

- filter=”data” / filter=”tar”

- symlink/hardlink bypass

- realpath / PATH_MAX

You can see these exact framings in NVD’s description, in advisory databases, and in supply-chain oriented summaries. (NVD)

Why does this matter for your article (and for your team)? Because the remediation story that resonates with engineers is not “patch Python.” It’s:

“Stop treating tar extraction as a harmless file operation—treat it as an input validation boundary in automation.”

That’s the bridge between “CVE details” and “real fixes that stick.”

The patch line: what fixes CVE-2025-4517 and why you shouldn’t treat it as a one-off

The June 2025 security release train for CPython included fixes for multiple tarfile extraction filter bypasses. The release announcement explicitly states: a CPython issue (gh-135034) fixed multiple problems that allowed tarfile extraction filters (filter="data" و filter="tar") to be bypassed using crafted symlinks and hard links, addressing CVE-2024-12718, CVE-2025-4138, CVE-2025-4330, CVE-2025-4435, and CVE-2025-4517. (Discussions on Python.org)

The related CPython issue thread also confirms this cluster treatment and cross-references the CVEs in scope. (جيثب)

This is the key lesson: tarfile extraction risk is a class, not a single bug. You should patch و standardize safe extraction patterns, because “the next tarfile CVE” will look familiar.

Before you talk about “PoC,” set a boundary: what you should and shouldn’t publish

Your keyword includes “poc,” but for responsible operations:

- Don’t publish or circulate “here’s how to craft a tarball that writes to X outside dest” in a way that’s turnkey for abuse.

- Do publish defensive PoC validation: reproducible checks that answer “are we exposed?” and “where would it happen in our systems?”

This article sticks to the defensive form: proof you’re not exposed و proof your guardrails work.

If you need the exploit mechanics for controlled research in an isolated lab, consult the technical advisory and keep it inside your security review loop. (جيثب)

Threat model: when “write outside extraction dir” becomes an incident

In many orgs, “write outside extraction dir” sounds generic—until you map it to real targets:

- Overwrite configuration used by a privileged service

- Drop a file into a directory that’s executed, imported, or loaded later (plugins, startup scripts)

- Modify build outputs (poison artifacts)

- Write into

.ssh/authorized_keysunder some service user (where permissions allow) - Change task configs in runner workspaces

Two factors make this a pipeline problem more than a desktop problem:

- extraction is often done by a privileged automation user

- the tarball source is often “semi-trusted” (third-party registries, cached artifacts, mirrored datasets)

That’s why supply-chain summaries focus on automation fragility: one crafted tarball breaks the trust chain. (Linux Security)

Quick “Are we exposed?” checklist the version you can paste into Slack

You are in the high-risk zone if كل شيء of these are true:

- قم بتشغيل Python 3.12+ somewhere (service, job, CI image, tooling container). (NVD)

- You extract tar archives from sources that can be influenced externally (downloads, uploads, registry pulls, mirrored artifacts).

- Your code calls

tarfileextraction usingextractall()أوextract()معfilter="data"أوfilter="tar"(directly or via wrappers). (NVD) - You don’t have a single hardened “safe extraction” implementation enforced across repos.

If your org’s immediate question is “what do we do by end of day,” jump to the sections on repo audit + safe extraction wrapper + CI enforcement.

Defensive PoC validation #1: repo-level audit that finds the real risk

Step 1: fast triage grep (good for first pass)

# Find tarfile usage and extraction calls

rg -n "tarfile\\.open|TarFile\\.extractall|\\.extractall\\(|TarFile\\.extract\\(|\\.extract\\(" .

# Find explicit filter usage

rg -n "filter\\s*=\\s*[\\"'](data|tar)[\\"']" .

This is quick, but it misses common patterns like:

from tarfile import open as tar_open- wrapper functions that hide extraction

- dynamic filter values

Step 2: AST audit (CI-friendly, fewer false negatives)

# audit_tarfile_filters.py

import ast

import pathlib

TARGET_METHODS = {"extractall", "extract"}

class Visitor(ast.NodeVisitor):

def __init__(self, filename: str):

self.filename = filename

def visit_Call(self, node: ast.Call):

func = node.func

if isinstance(func, ast.Attribute) and func.attr in TARGET_METHODS:

for kw in node.keywords:

if kw.arg == "filter":

if isinstance(kw.value, ast.Constant) and kw.value.value in ("data", "tar"):

print(f"[HIGH] {self.filename}:{node.lineno} {func.attr}(filter={kw.value.value!r})")

else:

print(f"[REVIEW] {self.filename}:{node.lineno} {func.attr}(filter=...)")

self.generic_visit(node)

def scan_repo(root: str = "."):

for py in pathlib.Path(root).rglob("*.py"):

try:

tree = ast.parse(py.read_text(encoding="utf-8"), filename=str(py))

except Exception:

continue

Visitor(str(py)).visit(tree)

if __name__ == "__main__":

scan_repo(".")

What you’re hunting for: extraction of untrusted tar content inside automation wrappers that the rest of the org assumes are “safe.”

Defensive PoC validation #2: container and runtime inventory (what actually runs in prod/CI)

The NVD record is explicit: Python 3.12+ is where this filter feature exists and where the vulnerability applies. (NVD)

So your fastest win is: find all Python 3.12+ runtimes in images and runners.

Check a running environment

python3 -V

python3 -c "import sys; print(sys.version)"

Check inside a container image (example pattern)

docker run --rm <your-image> python3 -V

CI runner reality check

If you pin GitHub Actions / CI images loosely (“latest”), assume you have drift. Record:

- base image tag

- python version

- whether patched versions are used (from your org’s patch policy)

Then apply the real fix: patch images and lock them.

The durable fix: stop trusting tarfile extraction semantics and enforce a safe extraction wrapper

Here’s a hardened extraction wrapper that intentionally rejects symlinks and hardlinks by default. The reason is not paranoia; it matches what CPython explicitly said it fixed: bypasses using crafted symlinks/hardlinks against extraction filters. (Discussions on Python.org)

Drop-in safe extraction helper

# safe_tar_extract.py

from __future__ import annotations

import os

import tarfile

from pathlib import Path

from typing import Optional

class UnsafeArchiveError(Exception):

pass

def _is_within_directory(base: Path, target: Path) -> bool:

"""

Ensure target resolves within base. Avoid TOCTOU-style assumptions.

"""

try:

base = base.resolve()

target = target.resolve()

return str(target).startswith(str(base) + os.sep)

except FileNotFoundError:

# If the file doesn't exist yet, resolve its parent.

return str(target.parent.resolve()).startswith(str(base.resolve()) + os.sep)

def safe_extract_tar(

tar_path: str | os.PathLike,

dest_dir: str | os.PathLike,

*,

max_members: Optional[int] = 20000,

max_total_size: Optional[int] = 2_000_000_000, # 2GB

) -> None:

dest = Path(dest_dir)

dest.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

total_size = 0

members_count = 0

with tarfile.open(tar_path, mode="r:*") as tf:

members = tf.getmembers()

for m in members:

members_count += 1

if max_members is not None and members_count > max_members:

raise UnsafeArchiveError("Too many archive members")

# safest default: reject all links

if m.issym() or m.islnk():

raise UnsafeArchiveError(f"Links are not allowed: {m.name}")

# reject absolute paths (Unix/Windows)

if m.name.startswith("/") or m.name.startswith("\\\\"):

raise UnsafeArchiveError(f"Absolute paths are not allowed: {m.name}")

# normalize + enforce boundary

target_path = (dest / m.name)

if not _is_within_directory(dest, target_path):

raise UnsafeArchiveError(f"Path traversal detected: {m.name}")

# size budget (tar bombs are a separate class of failure)

if m.size is not None:

total_size += int(m.size)

if max_total_size is not None and total_size > max_total_size:

raise UnsafeArchiveError("Archive too large")

# extract only after full validation

tf.extractall(dest)

“But we need symlinks”

If you truly need symlinks/hardlinks, implement link target resolution and enforce that the resolved destination is still within dest. This is harder than it sounds because you must guard against:

- link chains

- non-existent targets at validation time

- platform edge cases

- TOCTOU risks

For most automation flows, disallowing links in untrusted archives is the most cost-effective decision.

How to make the fix stick across dozens of repos

Patching runtime versions solves today’s CVE. Standardizing extraction behavior solves the next one.

A practical rollout pattern

- Patch Python in base images and runners to versions that include the tarfile fixes. (Discussions on Python.org)

- Ban direct

extractall()in code review (Semgrep / AST / PR checks). - Provide a shared library (

safe_extract_tar) and require it for any untrusted archive input. - Run “archive input” through a trust classification:

- trusted internal build artifact (still validate)

- mirrored third party (validate + hash allowlist)

- external/user supplied (strict validate + isolation)

- Constrain the file system where extraction happens:

- read-only root FS

- dedicated writable workspace

- least privilege user

- Add an operational “tripwire”: log and alert on attempted boundary violation (even if blocked).

This is why supply-chain oriented writeups treat this as automation fragility, not just “a parsing bug.” (Linux Security)

A short mapping of related CVEs in the same tarfile cluster and why you should mention them

If you publish an article titled “CVE-2025-4517 PoC,” readers will immediately ask: “Is this the only tarfile issue?”

The CPython security release announcement makes it clear this fix batch addressed multiple tarfile extraction filter bypass CVEs together, including CVE-2025-4517 and peers like CVE-2025-4435. (Discussions on Python.org)

So the right framing is:

- CVE-2025-4517: critical write boundary failure under filter-based extraction of untrusted archives (NVD scope: Python 3.12+). (NVD)

- CVE-2025-4435 and others: related bypass behaviors in tarfile extraction filtering that reinforce the same lesson: filters are not a security boundary unless you enforce them as one. (Discussions on Python.org)

This helps your readers understand why “just passing filter="data"” was never a sufficient security story.

What to tell engineers who ask “So is pip install dangerous now?”

NVD includes an important nuance that prevents misunderstanding: “source distribution archives are often extracted automatically when building, but the build process itself can already execute arbitrary code.” (NVD)

Translated into practical guidance:

- This CVE doesn’t newly “make sdist installs unsafe”—they already require trust because builds can run code.

- It does newly spotlight how many workflows treat tar extraction as “data-only,” especially in automation, ML pipelines, and artifact processing.

Your article should keep that nuance, because it builds credibility with the audience you described (hardcore, skeptical engineers).

If your audience cares about automated validation and pentest-assisted verification, CVE-2025-4517 is a clean example of what mature programs do:

- إثبات fleet/container versions are remediated,

- إثبات risky extraction patterns are removed from repos,

- إثبات safe extraction wrappers are enforced,

- إثبات controls still hold when engineers change code six months from now.

That’s exactly the niche where a workflow tool like Penligent (https://penligent.ai/) is relevant: turning “we think we fixed it” into repeatable tasks + evidence + reports—without pretending it replaces core fixes like patching runtimes and enforcing safe extraction. (penligent.ai)

If your readers already follow Penligent’s “PoC-as-validation” style, you can cross-link to the internal articles at the end (included below). (penligent.ai)

المراجع

- National Vulnerability Database — CVE-2025-4517 detail (scope, conditions, CVSS) (NVD)

- CVE.org — CVE record (use for canonical linking) (NVD)

- Python.org / CPython security releases announcement (tarfile CVE cluster, fixed versions) (Discussions on Python.org)

- GitHub advisory entry for CVE-2025-4517 (good cross-reference) (جيثب)

- Red Hat — CVE-2025-4517 page (enterprise distro framing) (Red Hat Customer Portal)

- Wiz vulnerability database entry (practical mitigation framing) (ويز.io)

- CPython issue tracking the multi-CVE tarfile filter bypass fix (engineering context) (جيثب)

- Google Security Research advisory (technical analysis; keep lab-only) (جيثب)

- CVE-2026-20841 PoC — “When Notepad Learns Markdown, a Click Can Become Execution” (penligent.ai)

- “Why Everyone’s Searching It — and How to Turn a News Habit Into a Security Workflow” (CVE-2026-20841 workflow framing) (penligent.ai)

- CVE-2026-20841 PoC — “When Just a Text Editor Becomes a Link-to-Code Execution Primitive” (penligent.ai)