Why CVE-2026-21510 is not “just another Patch Tuesday line item”

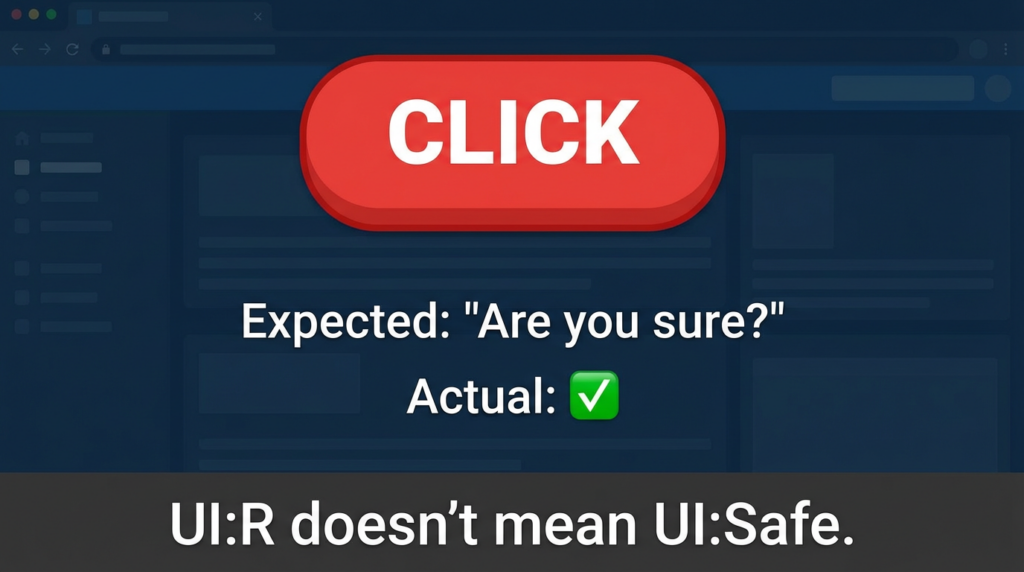

CVE-2026-21510 is described by Microsoft / National Vulnerability Database as a protection mechanism failure in Windows Shell that allows an unauthorized attacker to bypass a security feature over a network, with CVSS v3.1 8.8 and vector AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:R/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H. (NVD)

That vector matters more than the label:

- Network-reachable + low complexity means it fits real phishing and lure distribution.

- No privileges required means it’s viable as an initial access step.

- User interaction required is the only “speed bump,” but the interaction is the most common one in enterprise: someone opens a file or clicks a link.

Multiple independent patch-day analyses highlight the same practical framing: this is an “alerts don’t fire when they should” problem—where the UX friction defenders rely on (SmartScreen / Shell warnings) becomes unreliable. (BleepingComputer)

What the vulnerability changes in real attack chains

Most teams treat SmartScreen / Shell prompts as a soft control—useful, but not something you bet the company on. CVE-2026-21510 is a reminder that attackers explicitly target these controls because they’re load-bearing in the early stages of compromise.

The recurring theme across high-signal reporting is:

- The trigger is a crafted link or shortcut file.

- The outcome is bypassing SmartScreen and Windows Shell prompts, letting attacker-controlled content run with less/no warning. (BleepingComputer)

Why that is a big deal:

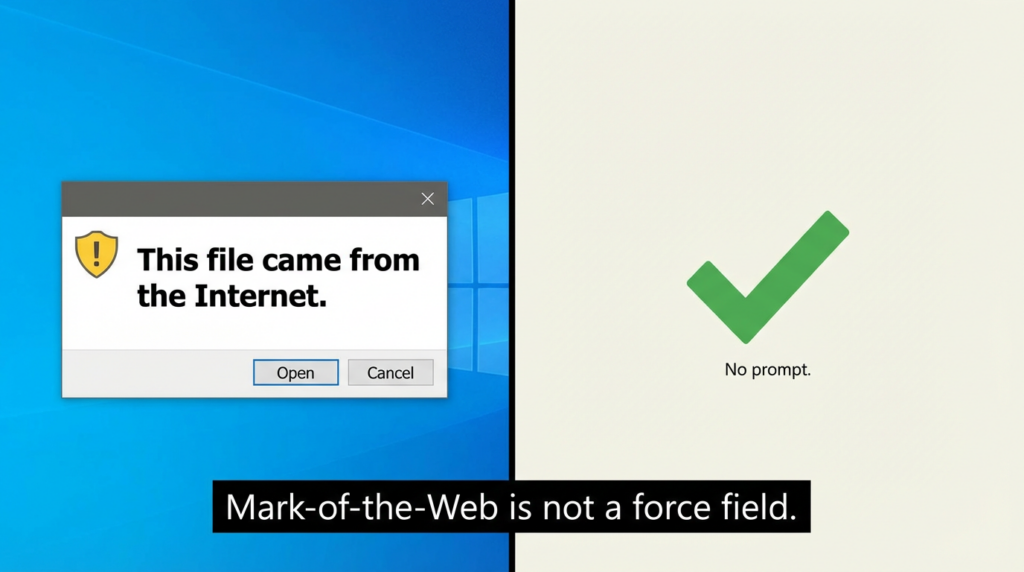

- It raises the success rate of initial access. If the user never sees the “this came from the internet” friction, the same lure converts more often.

- It compresses time-to-impact. One click can take you from delivery to execution without the usual “ask for consent” step. Krebs summarized it as a single click that can quietly bypass protections and run attacker-controlled content. (Krebs on Security)

- It chains cleanly into privilege escalation. Patch-day trackers consistently group CVE-2026-21510 with exploited EoPs like CVE-2026-21519 (DWM) and CVE-2026-21533 (RDS) because bypass → code execution foothold → SYSTEM is a classic path. (Tenable®)

The “highest-click” angle defenders should internalize

If you scan the coverage that tends to win clicks and get re-shared in admin circles (Patch Tuesday megathreads, blue-team recaps, enterprise security newsletters), the language that keeps recurring is:

- “Six actively exploited zero-days” (urgency + volume) (BleepingComputer)

- “SmartScreen bypass” (instantly understandable impact) (Malwarebytes)

- “One click” / “single malicious link” (low effort for attacker, high risk for org) (CyberScoop)

That click-driven framing is actually useful for defenders—because it captures the operational truth: this is a reliability upgrade for social engineering.

Scope and impact: what we can say with high confidence

Here’s what is strongly supported across primary/credible sources:

- Severity & classification: CVSS 8.8; “protection mechanism failure” (CWE-693); Windows Shell security feature bypass. (NVD)

- Exploit status: reported as aktiv genutzt prior to patch availability, and publicly disclosed. (Tenable®)

- User interaction: attacker must convince a user to open a malicious link or shortcut file. (BleepingComputer)

- Patch cycle context: part of February 2026 Patch Tuesday with multiple exploited zero-days. (BleepingComputer)

One caveat: detailed exploitation mechanics are not publicly described in a way defenders can fully reproduce end-to-end from vendor text alone—and that’s normal for exploited-in-the-wild issues.

Related CVEs you should model alongside CVE-2026-21510

Attackers don’t “do CVEs.” They do chains. In February 2026 reporting, CVE-2026-21510 is repeatedly grouped with these exploited issues:

| CVE | Komponente | Klasse | Why it matters operationally | Exploited noted by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2026-21510 | Windows Shell | Security feature bypass | Suppresses safety prompts; boosts lure conversion | BleepingComputer, Tenable, Zero Day Initiative (BleepingComputer) |

| CVE-2026-21513 | MSHTML (Trident) | Security feature bypass | Similar “prompt bypass” orbit; legacy rendering still matters | (BleepingComputer) |

| CVE-2026-21514 | Word | Security feature bypass | Office open workflows remain high-volume initial access | (Tenable®) |

| CVE-2026-21519 | Desktop Window Manager | Ausweitung der Privilegien | Post-foothold escalation to SYSTEM patterns | (Tenable®) |

| CVE-2026-21533 | Remote Desktop Services | Ausweitung der Privilegien | Lateral movement / SYSTEM escalation on RDS systems | (Tenable®) |

| CVE-2026-21525 | RasMan | DoS | Exploited DoS is unusual; still signals attention | (Tenable®) |

And if you want a “same story, different surface” historical anchor for your threat model, CVE-2025-0411 (7-Zip Mark-of-the-Web bypass) is a clean parallel: it’s another case where internet-origin trust signals fail to propagate, reducing user-facing friction and making downstream execution easier. (NVD)

Triage playbook: what to do in the first 24–72 hours

1) Patch prioritization that matches attacker reality

February 2026 had an unusually high count of exploited issues; CrowdStrike and SecurityWeek both emphasize the six exploited zero-days as the headline risk. (CrowdStrike)

ZDI explicitly calls out that a one-click bypass-to-execution class bug is rare and worth fast deployment. (Zero Day Initiative)

Practical priority order for endpoints:

- Wave 0 (same day): security/admin workstations, developer machines with secrets, EDR consoles, jump boxes.

- Wave 1 (24–48h): all user endpoints that receive email/web content.

- Wave 2 (week 1): remaining endpoints; special fleets.

- Wave 3 (asap but careful): kiosks/VDI images/legacy app constraints.

2) Reduce exposure while patching rolls out

This is not about “perfect mitigation,” it’s about shrinking the conversion funnel.

- Increase friction on file types that act as “launchers” (shortcuts, script files, disk images) from internet origin.

- Tighten email and web filtering for LNK/ISO/VHD/HTML attachment patterns.

- Turn on/validate endpoint rules that block common post-click behaviors.

If your org already uses Microsoft Defender, prioritize:

- Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) rules that restrict Office-child-process patterns and script behaviors.

- Mark-of-the-Web preservation across download/extraction flows.

(Exact rule selection depends on your environment; the point is to raise cost for “one click → execution.”)

Detection and hunting: how to catch “the prompt didn’t show up”

CVE-2026-21510 is a bypass, not a payload. So hunting is about correlating user-initiated opens with suspicious downstream execution.

What to look for

High-signal patterns (generally useful, regardless of exact exploit mechanics):

- A shortcut/link open event followed by:

- script engines (PowerShell, wscript/cscript),

- LOLBins (rundll32, regsvr32, mshta),

- unexpected child processes from Explorer/Shell,

- network beacons shortly after a user interaction.

KQL starter queries

// 1) Explorer spawning suspicious scripting/LOLBins shortly after user activity

DeviceProcessEvents

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "explorer.exe"

| where FileName in~ ("powershell.exe","pwsh.exe","wscript.exe","cscript.exe","mshta.exe","rundll32.exe","regsvr32.exe","cmd.exe")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName, FileName, ProcessCommandLine,

InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessParentFileName

| order by Timestamp desc

// 2) Suspicious file extensions in command lines that commonly act as launchers

DeviceProcessEvents

| where ProcessCommandLine has_any (".lnk", ".url", ".hta", ".js", ".jse", ".vbs", ".vbe", ".wsf", ".iso", ".vhd", ".vhdx")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName, FileName, ProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessFileName

| order by Timestamp desc

// 3) “Click -> immediate network” (rough heuristic)

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where InitiatingProcessFileName in~ ("powershell.exe","mshta.exe","rundll32.exe","wscript.exe","cscript.exe","cmd.exe")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, InitiatingProcessAccountName, InitiatingProcessFileName,

RemoteUrl, RemoteIP, RemotePort, InitiatingProcessCommandLine

| order by Timestamp desc

These are intentionally generic: they hunt the behavioral consequence that bypass bugs are designed to enable.

Sigma-style logic (portable)

title: Suspicious Explorer Child Process After Potential Shortcut/Link Open

id: 8c2d7c3a-2151-0byp-9f31-4b0b8e10a001

status: experimental

description: Detects explorer.exe spawning scripting engines or LOLBins often used after user-initiated link/shortcut execution.

logsource:

product: windows

category: process_creation

detection:

selection_parent:

ParentImage|endswith: '\\explorer.exe'

selection_child:

Image|endswith:

- '\\powershell.exe'

- '\\pwsh.exe'

- '\\wscript.exe'

- '\\cscript.exe'

- '\\mshta.exe'

- '\\rundll32.exe'

- '\\regsvr32.exe'

- '\\cmd.exe'

condition: selection_parent and selection_child

falsepositives:

- Admin scripts launched from Explorer

level: high

Enterprise hardening: make “internet-origin execution” expensive again

Re-establish the trust boundary you thought you had

CVE-2026-21510 is, fundamentally, a trust-boundary failure: “content that should be treated as risky is treated as safe enough to run without the normal prompts.” (NVD)

So your hardening goal is not “block the CVE.” It’s:

- Ensure risky-origin files are constrained even if a prompt is bypassed.

- Prevent common execution pivots (scripts, LOLBins, Office → child processes).

- Detect the residual traces when bypass succeeds.

Practical controls to review

- Mark-of-the-Web handling and propagation

- Validate that downloaded files keep Zone.Identifier where expected.

- Watch archive extractors and edge cases (the 7-Zip CVE-2025-0411 story exists because MoTW propagation breaks in the real world). (NVD)

- Application control

- WDAC / AppLocker policies for script hosts and unsigned binaries in user-writable paths.

- Constrain mshta/rundll32/regsvr32 in environments where they’re not needed.

- Attack Surface Reduction rules

- Especially rules that stop common “initial access → execution” bridges.

Verification at scale: scripts you can actually run

Inventory whether key February 2026 patches are present (basic approach)

You’ll need to adapt KB IDs to your specific OS builds and servicing channels; use your patch management source of truth. This is a workflow template:

# Pull recent security updates and surface anything around Patch Tuesday time

Get-HotFix |

Where-Object { $_.InstalledOn -ge (Get-Date "2026-02-01") -and $_.InstalledOn -le (Get-Date "2026-02-28") } |

Sort-Object InstalledOn -Descending |

Select-Object InstalledOn, HotFixID, Description

Find risky launcher files in user download locations

$targets = @("$env:USERPROFILE\\Downloads", "$env:USERPROFILE\\Desktop", "$env:USERPROFILE\\Documents")

$ext = @("lnk","url","hta","js","jse","vbs","vbe","wsf","iso","vhd","vhdx")

Get-ChildItem $targets -Recurse -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue |

Where-Object { $ext -contains $_.Extension.TrimStart(".").ToLowerInvariant() } |

Select-Object FullName, Length, LastWriteTime |

Sort-Object LastWriteTime -Descending |

Select-Object -First 200

This is not “IOC hunting.” It’s helping you find where user-click execution tends to originate, so you can tighten policy and education.

When the failure mode is “trust boundary”

If your testing program still treats “SmartScreen prompt appears” as a given, CVE-2026-21510 is the kind of issue that makes that assumption brittle.

Two practical ways Penligent.ai can help without hand-waving:

- Regression testing security UX assumptions as part of continuous security validation. When Windows components change, you want automated checks that confirm risky-origin artifacts still trigger the guardrails you rely on (MoTW handling, prompt behavior, execution constraints). Penligent’s AI-assisted workflow is well-suited to turning these “tribal knowledge” checks into repeatable tasks that can be re-run after patch cycles.

- Attack-chain modeling for defenders, not exploit development. The value is in simulating the defensive question: “If a user clicks a launcher artifact, what downstream execution paths are still possible in our environment?” That’s a control validation exercise—measuring where WDAC/ASR/email protections stop the chain, and where they don’t.

If you want a quick starting point, Penligent has already published deeper context on this vulnerability and adjacent Windows execution-boundary issues (see links below).

Bottom line for defenders

CVE-2026-21510 is a blunt reminder: the Windows “are you sure?” moment is part of your security model, whether you admit it or not. When that moment can be bypassed in the wild, the organization that wins is the one that:

- patches fast und

- hunts behaviorally und

- hardens the trust boundary so bypass ≠ execution.

February 2026 was noisy for a reason—credible patch-day reviewers called the exploited count “extraordinarily high,” and the most operationally dangerous items were the ones that make user interaction safer by default… until they don’t. (Zero Day Initiative)

Referenzen

- National Vulnerability Database — CVE-2026-21510 record (CVSS vector, CWE-693) (NVD)

- CVE.org — CVE-2026-21510 record (CVE)

- BleepingComputer — February 2026 Patch Tuesday summary + Microsoft advisory quotes (BleepingComputer)

- Zero Day Initiative — Security Update Review emphasizing rarity/urgency (Zero Day Initiative)

- Tenable — CVE-2026-21510 + related exploited CVEs context (Tenable®)

- CrowdStrike — February 2026 Patch Tuesday risk analysis (CrowdStrike)

- Malwarebytes — Defender-focused explanation of the bypass pattern (Malwarebytes)

- Krebs on Security — Defender-friendly recap with practical framing (Krebs on Security)

- Penligent — “CVE-2026-21510: When the Prompt Doesn’t Show Up” (penligent.ai)

- Penligent — “CVE-2026-21510 PoC: The SmartScreen Moment That Never Happens” (defender-oriented discussion) (penligent.ai)

- Penligent — “Windows Notepad CVE: When Markdown Turns Text Into an Execution Boundary” (adjacent execution-boundary theme) (penligent.ai)

- Penligent — “7-Zip CVE: When Extract Becomes the First Step of an Attack Chain” (MoTW propagation parallels) (penligent.ai)