filter() for Security Engineers: Deterministic Pipelines, Fewer False Positives, and Zero “Filter-as-Sanitizer” Myths

If you searched “javascript filter”, odds are you want one of these outcomes:

- Turn noisy scan output into a clean, 실행 가능 shortlist.

- Filter arrays of objects (assets, findings, IOCs, rules) without writing spaghetti loops.

- Make filtering fast enough to run inside CI, a browser sandbox, or a security pipeline.

- Avoid the classic trap: “filtering strings” ≠ “making untrusted input safe”.

That last one is where a lot of security tooling quietly fails.

There’s a reason the long-tail query “javascript filter array of objects” is evergreen: a canonical Stack Overflow thread titled exactly that sits at “Viewed 228k times”, which is a strong signal of what practitioners actually click, copy, and deploy. (Stack Overflow)

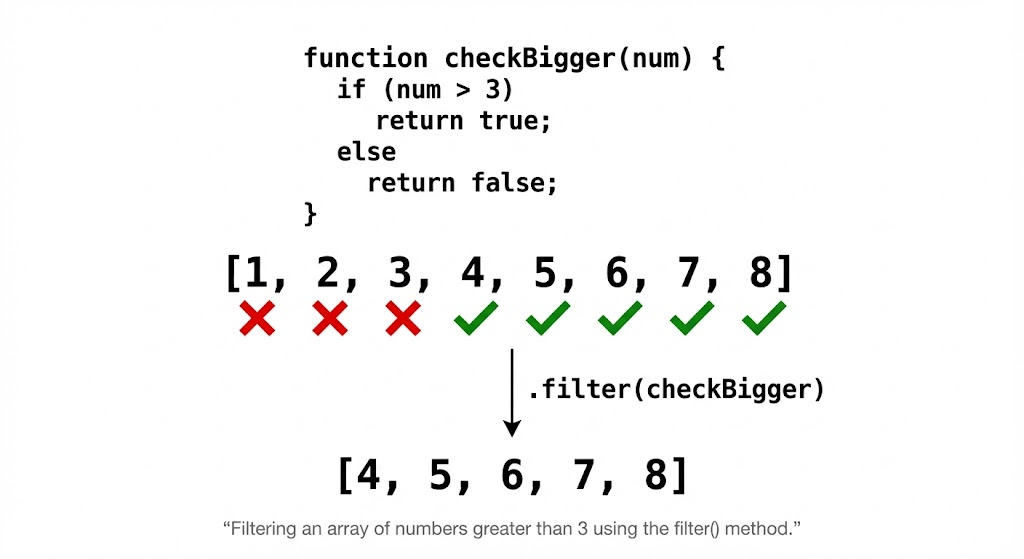

What Array.prototype.filter() guarantees (and what it absolutely doesn’t)

At the language level, filter():

- Returns a new array containing elements whose predicate returns truthy.

- Produces a shallow copy (object references are shared, not cloned). (MDN 웹 문서)

- Skips empty slots in sparse arrays (your predicate is not called for “holes”). (TC39)

MDN is explicit on both “shallow copy” and “not invoked for empty slots in sparse arrays.” (MDN 웹 문서)

The ECMAScript spec also explicitly notes callbacks are not called for missing elements. (TC39)

Why sparse arrays matter in security pipelines

Sparse arrays show up more than you’d expect: JSON transforms, “delete index” bugs, partial results from multi-source merging, or naive deduping.

const results = [ {id: 1}, , {id: 3} ]; // note the hole

const kept = results.filter(() => true);

console.log(kept); // [{id: 1}, {id: 3}] (hole disappears)

If your pipeline assumes “same length in, same length out”, sparse arrays will break it. In a triage pipeline, that can translate into silent data loss.

The high-CTR pattern: filtering arrays of objects

Most real “javascript filter” usage is filtering arrays of objects (assets/findings/IOCs).

Example: keep only exploitable web findings with evidence attached

const findings = [

{ id: "XSS-001", type: "xss", severity: "high", verified: true, evidence: ["req.txt", "resp.html"] },

{ id: "INFO-009", type: "banner", severity: "info", verified: false, evidence: [] },

{ id: "SSRF-004", type: "ssrf", severity: "critical", verified: true, evidence: ["dnslog.png"] },

];

const actionable = findings.filter(f =>

f.verified &&

(f.severity === "high" || f.severity === "critical") &&

f.evidence?.length > 0

);

console.log(actionable.map(f => f.id)); // ["XSS-001", "SSRF-004"]

Example: scope control (the easiest place to ruin your program)

const inScopeHosts = new Set(["api.example.com", "admin.example.com"]);

const assets = [

{ host: "api.example.com", ip: "203.0.113.10", alive: true },

{ host: "cdn.example.com", ip: "203.0.113.11", alive: true },

{ host: "admin.example.com", ip: "203.0.113.12", alive: false },

];

const targets = assets

.filter(a => a.alive)

.filter(a => inScopeHosts.has(a.host));

console.log(targets);

// [{host:"api.example.com", ...}]

Using a 설정 avoids the accidental O(n²) pattern (includes() inside filter() across large arrays). This matters when you’re filtering tens of thousands of assets.

Performance reality: packed vs holey arrays and why you should care only a little

V8 has a well-known distinction between packed 그리고 holey arrays; operations on packed arrays are generally more efficient than on holey arrays. (V8)

Security implication: pipelines that create holes (delete arr[i], sparse merges) can degrade performance 그리고 correctness. The practical rule is simple:

- Don’t create holes. Prefer

splice,filter, or rebuild arrays. - Avoid mixing types in hot arrays if you’re processing large datasets.

A security engineer’s decision table: filter vs some vs find vs 감소

| Goal in a security pipeline | Best tool | 왜 | Common mistake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keep all matches (shortlist) | filter() | Returns a subset array | Mutating source during predicate |

| Stop at first match (policy gate) | some() | Early exit boolean | filter().length > 0 |

| Get first match (route selection) | find() | Early exit + element | filter()[0] |

| Build metrics (counts, scores) | reduce() | One-pass aggregation | Doing expensive I/O in reducer |

This is less about style and more about making your pipeline deterministic and cheap enough to run everywhere (CI, browser sandbox, agent runners).

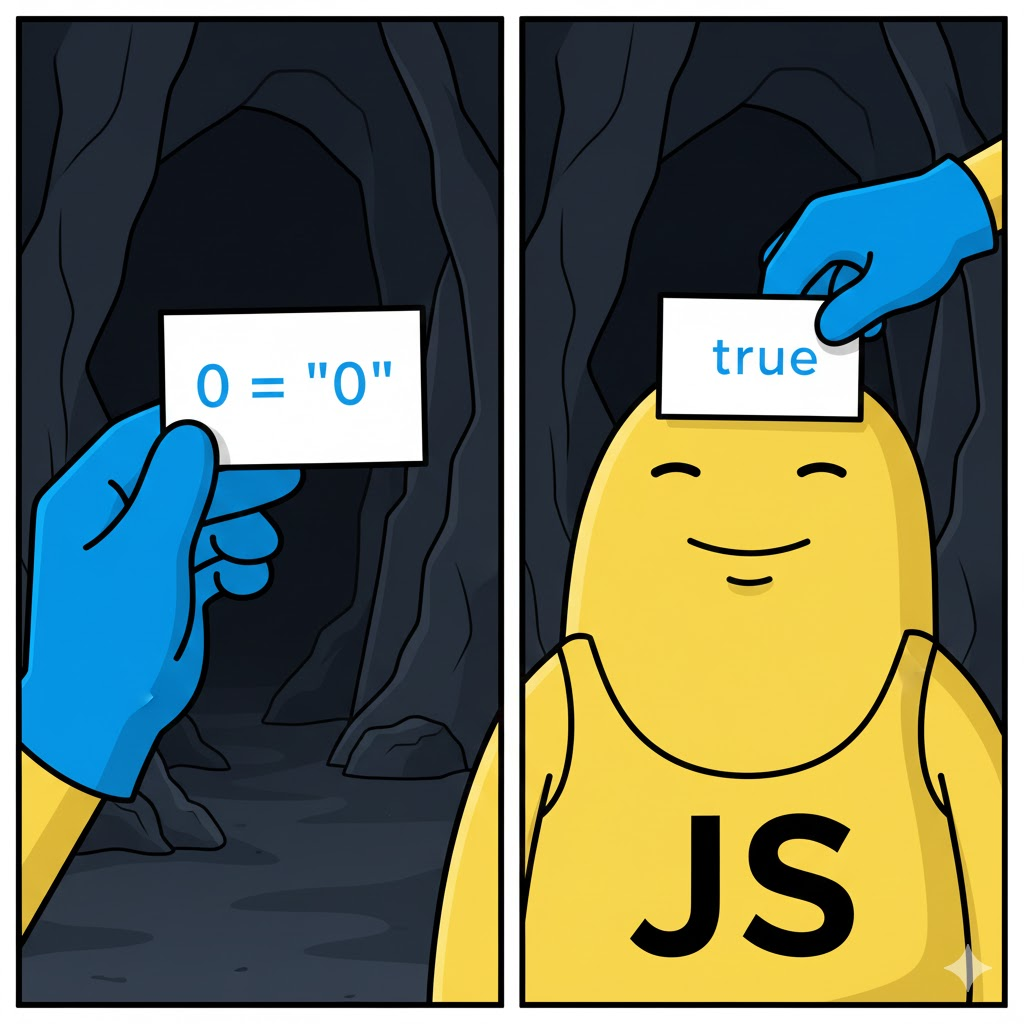

The dangerous overload: “filtering” is not “sanitization”

Now the part that security engineers should be ruthless about: string filtering is not a security boundary.

OWASP’s XSS Prevention guidance emphasizes output encoding (and using the right defense for the right context) rather than relying on input filtering. (OWASP 치트 시트 시리즈)

OWASP’s own XSS Filter Evasion content explicitly frames input filtering as an incomplete defense and catalogs bypasses. (OWASP 치트 시트 시리즈)

PortSwigger’s XSS cheat sheet (updated Oct 2025) is similarly explicit that it includes vectors that help bypass WAFs and filters. (포트스위거)

A realistic example: URL “filters” that collapse under parsing differences

Bad pattern:

function allowUrl(u) {

return !u.includes("javascript:") && !u.includes("data:");

}

Better pattern: parse + allowlist + normalize:

function allowUrl(u, allowedHosts) {

const url = new URL(u, "<https://base.example>"); // safe base for relative inputs

if (!["https:"].includes(url.protocol)) return false;

return allowedHosts.has(url.hostname);

}

const allowedHosts = new Set(["docs.example.com", "cdn.example.com"]);

This is the mental shift: stop matching strings, start validating structured data.

CVEs that prove “filters/sanitizers” fail in production and why you should bake them into your checks

When your organization says “we sanitize HTML”, your threat model should immediately include: which sanitizer, which version, which config, and which bypass history?

CVE-2025-66412 (Angular template compiler stored XSS)

NVD describes a stored XSS in Angular’s template compiler due to an incomplete internal security schema that can allow bypassing Angular’s built-in sanitization; fixed in patched versions. (NVD)

Security takeaway: “framework sanitization” is not a permanent guarantee. Treat it like any other security control: version, advisory, regression tests.

CVE-2025-26791 (DOMPurify mXSS via incorrect regex)

NVD states DOMPurify before 3.2.4 had an incorrect template-literal regex that can lead to mutation XSS in some cases. (NVD)

Security takeaway: sanitizer options matter. Config combos can create exploit conditions even when you “use a respected library.”

CVE-2024-45801 (DOMPurify depth-check bypass + prototype pollution weakening)

NVD reports special nesting techniques could bypass depth checking; prototype pollution could weaken it; fixed in later versions. (NVD)

Security takeaway: defenses that rely on heuristics (depth limits, nesting checks) often become bypass targets.

CVE-2025-59364 (express-xss-sanitizer recursion DoS)

NVD notes unbounded recursion depth during sanitization of nested JSON request bodies; GitHub advisory details impact and fixed versions. (NVD)

Security takeaway: “sanitization” code can introduce availability bugs. Attackers don’t need XSS if they can crash your service reliably.

Practical “javascript filter” patterns for pentest automation

1) Confidence gating: keep only high-confidence candidates for expensive verification

const candidates = [

{ id: "C1", signal: 0.92, cost: 3.0 },

{ id: "C2", signal: 0.55, cost: 1.2 },

{ id: "C3", signal: 0.81, cost: 9.5 },

];

const budget = 10;

const shortlist = candidates

.filter(c => c.signal >= 0.8) // confidence threshold

.filter(c => c.cost <= budget); // cheap enough to verify

console.log(shortlist.map(c => c.id)); // ["C1"]

2) Evidence completeness: don’t let reports ship without proof

const reportItems = findings.filter(f =>

f.verified &&

Array.isArray(f.evidence) &&

f.evidence.length >= 1

);

3) Kill-switch filters: enforce policy before any exploitation step

사용 some() for “deny if any matches”:

const forbidden = [/\\.gov$/i, /\\.mil$/i];

const isForbidden = host => forbidden.some(rx => rx.test(host));

Where Penligent fits

In an “evidence-first” workflow, filter() is great for deterministic orchestration: deciding what to verify next, which paths to explore, and what makes it into the final report. The hard part is the verification loop: reproducing, collecting proof, and keeping results consistent across runs.

That’s the kind of place an AI-driven pentest platform can fit naturally: you filter candidates in code, then use an automated system to validate, capture evidence, and keep execution consistent across environments. Penligent’s positioning as an AI pentest platform makes sense specifically in that “verify + evidence + report” segment of the pipeline.

Penligent: https://penligent.ai/

A short checklist to keep “javascript filter” usage security-grade

- 치료

filter()as data shaping, not “input sanitization.” - Avoid sparse arrays; remember callbacks are skipped for empty slots. (TC39)

- 사용

설정/지도for membership filters at scale. - Prefer

some()/find()when you need early exit. - For XSS defense, follow OWASP’s context-based encoding guidance, not blacklist filters. (OWASP 치트 시트 시리즈)

- Track sanitizer/framework CVEs as first-class supply-chain risk. (NVD)

References & authoritative links (copy/paste)

- MDN

Array.prototype.filter(): https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array/filter (MDN 웹 문서) - ECMAScript spec note on skipping missing elements: https://tc39.es/ecma262/multipage/indexed-collections.html (TC39)

- V8 “Elements kinds” (packed vs holey): https://v8.dev/blog/elements-kinds (V8)

- Stack Overflow “javascript filter array of objects” (Viewed 228k times): https://stackoverflow.com/questions/13594788/javascript-filter-array-of-objects (Stack Overflow)

- OWASP XSS Prevention Cheat Sheet: https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Cross_Site_Scripting_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet.html (OWASP 치트 시트 시리즈)

- OWASP XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet: https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/XSS_Filter_Evasion_Cheat_Sheet.html (OWASP 치트 시트 시리즈)

- PortSwigger XSS Cheat Sheet (2025): https://portswigger.net/web-security/cross-site-scripting/cheat-sheet (포트스위거)

- NVD CVE-2025-66412 (Angular stored XSS): https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-66412 (NVD)

- Angular advisory (CVE-2025-66412): https://github.com/angular/angular/security/advisories/GHSA-v4hv-rgfq-gp49 (GitHub)

- NVD CVE-2025-26791 (DOMPurify mXSS): https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-26791 (NVD)

- NVD CVE-2024-45801 (DOMPurify depth-check bypass): https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-45801 (NVD)

- NVD CVE-2025-59364 (express-xss-sanitizer DoS): https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2025-59364 (NVD)

- GitHub advisory GHSA-hvq2-wf92-j4f3: https://github.com/advisories/GHSA-hvq2-wf92-j4f3 (GitHub)