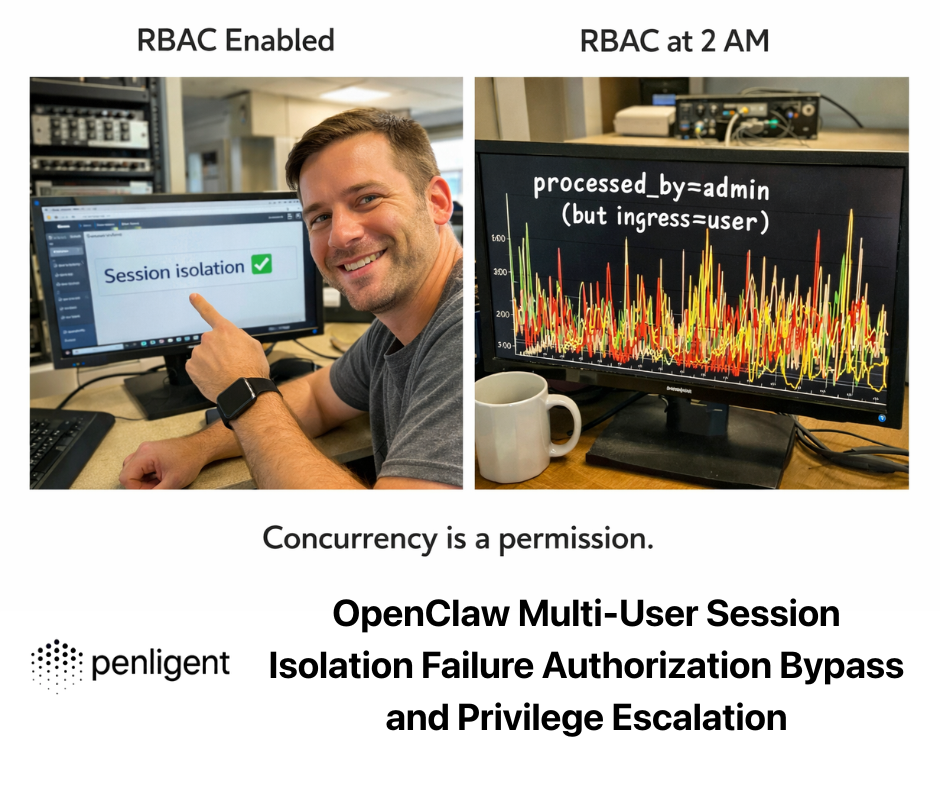

1) What happened and why this is bigger than “a few bad plugins”

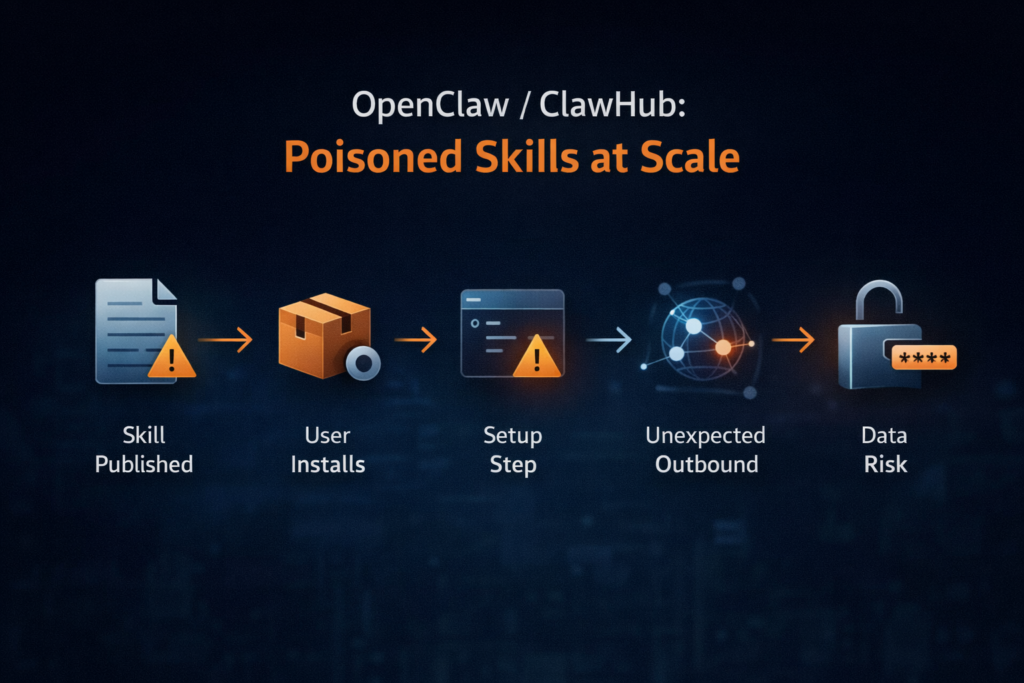

In early February 2026, OpenClaw’s public skill marketplace (ClawHub) became the center of a fast-moving supply-chain poisoning event: security researchers found hundreds of malicious skills that used social engineering and obfuscated “setup” instructions to trick users into running commands that ultimately installed credential-stealing malware. Reporting ties the bulk of findings to a primary campaign dubbed ClawHavoc, and multiple outlets describe infostealer delivery affecting macOS and Windows users. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

The headline number that matters operationally isn’t just “malicious skills exist.” It’s the ratio e distribution: Koi Security reported auditing thousands of skills and finding 341 malicious entries, with 335 attributed to a single coordinated campaign. (Koi) That concentration is a signal you can use for defense: this wasn’t a random trickle of one-off junk; it was a playbook executed at scale.

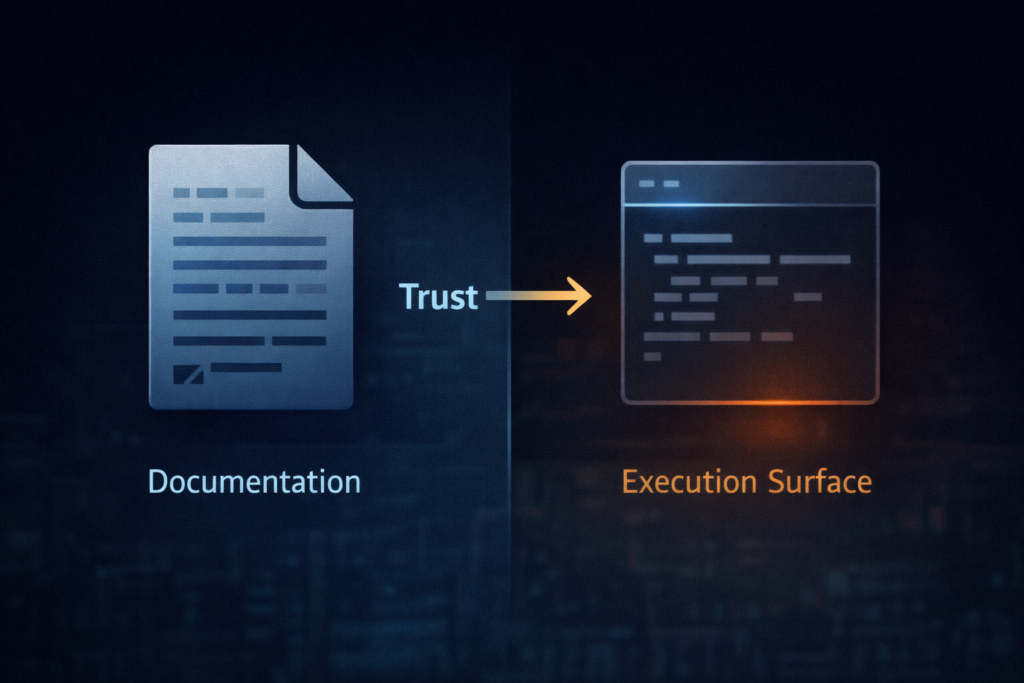

The structural risk is even more important than the count. In this ecosystem, the critical “execution surface” isn’t always a compiled artifact or a package install script you can reproducibly build and verify. Researchers and analysts repeatedly point to a pattern where the skill’s documentation—often a SKILL.md file—becomes the real delivery mechanism. In plain terms: a Markdown file becomes an installer. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

This is why the OpenClaw/ClawHub incident feels different from classic package-registry threats. With npm or PyPI, you usually defend by securing build pipelines, pinning versions, verifying integrity, and watching maintainer behavior. With agent skills, you also need to defend against something more human and more slippery: instructional supply chain—where “the code” is partly a set of steps that a user (or an agent acting on their behalf) is coaxed into executing.

2) The fastest question: “Am I exposed?”

If you—or anyone on your team—installed OpenClaw skills from ClawHub during the relevant window, you should treat this as a real incident until proven otherwise. Multiple sources describe skills masquerading as productivity, automation, or crypto tools, and delivering credential theft and data exfiltration malware (including AMOS / “Atomic macOS Stealer”). (Notícias do Hacker)

Exposure checklist (high signal, low noise)

You are in the high-risk group if any of the following are true:

- You installed skills directly from ClawHub rather than from an internal mirror/allowlist. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

- You or your agent followed “setup” instructions that included:

- obfuscated one-liners (Base64 decoding, encoded PowerShell, opaque “installer” blobs), or

- “download and run” patterns (e.g., fetch remote script, then execute)—even if you didn’t fully understand what the command did. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

- The skill had a theme that implies strong local access (wallet management, trading bots, inbox/calendar automation, CLI wrappers). (Notícias do Hacker)

If you’re in that group, the right operating stance is assume compromise until your host and secrets are validated.

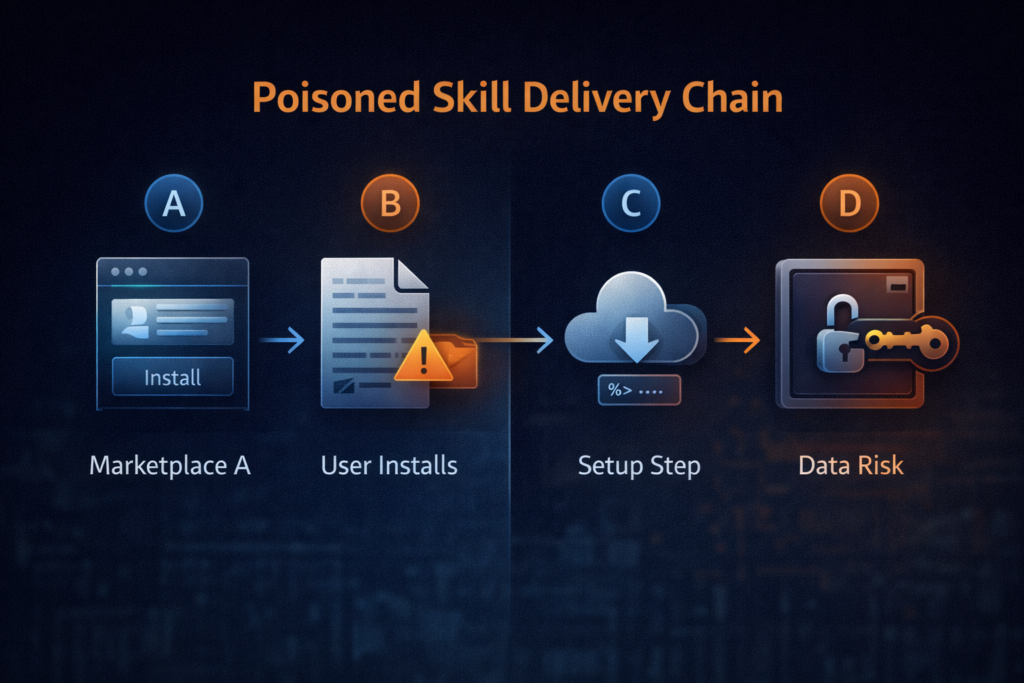

3) The attack chain (defender’s view): how a “skill” becomes malware

You don’t need attacker-grade detail to defend effectively. What you need is a clean mental model you can map to telemetry.

Across reporting and research writeups, the core chain looks like this:

Stage A — Trust acquisition (the marketplace problem)

Attackers publish skills that look legitimate (names, descriptions, icons, sometimes even functional behavior). The marketplace offers distribution, and the social proof of “this is a shared skill registry” does the rest. (Koi)

Stage B — Instructional execution (the SKILL.md problem)

Instead of shipping an obviously malicious binary, many poisoned skills rely on “prerequisites” or “installation steps” that instruct the user to run a command. Analysts highlight obfuscation patterns (Base64 blobs, staged scripts) that reduce the chance a human recognizes the danger. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

This is the key concept: the marketplace shipped a persuasive document, not necessarily a single executable artifact. That makes integrity verification and static scanning harder, because the “payload” is often remote, dynamic, and one step away.

Stage C — Staging (downloaders and second-stage payloads)

Once a user runs a setup command, it fetches additional content from a remote endpoint and executes it. Multiple outlets connect this to infostealer delivery, including AMOS on macOS, and other malware categories like keyloggers and backdoors. (Mídia SC)

Stage D — Collection and exfiltration (the credential gravity well)

The targets are predictable because the environment is rich: browser passwords, API keys, SSH keys, crypto wallet data, and anything in env vars or dotfiles. The broader warning from ecosystem research is blunt: agent skills can inherit shell access e filesystem access through the agent’s privileges. (Snyk)

4) Why agent skills are “worse than npm” (and how to explain this to leadership)

This section is for the moment when your CISO, CTO, or CEO asks: “How is this different from any other open-source risk?”

It’s different in four ways.

4.1 The permission model is inverted

Traditional package ecosystems often execute code in constrained contexts:

- a build system container,

- a CI job with scoped credentials,

- an app sandbox with limited entitlements (at least in theory).

Agent skills can operate with the full permissions of the agent—and the agent is often configured specifically to do powerful things: read your files, run shell commands, connect to Slack/email, and automate workflows. (Snyk)

So the extension ecosystem is attached to something that is already privileged by design. That makes “just don’t run untrusted code” a fantasy; the entire selling point is that the agent runs things.

4.2 The artifact is not always code; it’s also instructions

In classic supply chain compromises, defenders can often anchor controls on:

- reproducible builds,

- signed releases,

- dependency locks,

- checksum verification.

Here, SKILL.md (or equivalent instruction surfaces) can drive the compromise by pushing a human into becoming the execution engine. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

You can’t SBOM your way out of a social-engineering install step unless you also govern instructions and user behavior.

4.3 The marketplace scaling function favors attackers

Every developer marketplace has this problem, but agent marketplaces are newer and often lack hardened governance. Koi Security’s writeup explicitly frames the pattern as “where developers congregate, attackers follow”—and skill hubs are now one of those congregations. (Koi)

4.4 The “AI layer” adds ambiguity, not safety

Some teams implicitly assume “the agent will know what’s safe.” But external analysis warns that letting an agent interpret untrusted content creates indirect-instruction pathways, and that the skill ecosystem itself becomes an attack surface. (1Password)

5) Stop-the-bleeding triage: what to do in the next 30 minutes

If you suspect a poisoned skill was installed, your goal is to prevent further damage antes de you chase perfect attribution.

Step 1 — Isolate the host, don’t “poke it” online

- Disconnect from networks where feasible (or quarantine VLAN).

- Disable unnecessary outbound access (block unknown domains; restrict egress to known good). This matters because staged payloads often need follow-on downloads or exfil.

Step 2 — Preserve evidence without running unknown commands

- Collect process trees, persistence mechanisms, recent network connections.

- Export shell history (bash/zsh), PowerShell transcripts on Windows if present.

- Snapshot relevant directories where skills are stored.

Step 3 — Rotate secrets as if they are compromised

Because the goal of these campaigns is credential theft, rotating secrets early is rational even if you later find no evidence of exfiltration. The cost of rotation is usually lower than the cost of being wrong.

Prioritize:

- password managers / browser sync accounts,

- SSH keys and Git tokens,

- cloud access keys,

- crypto wallets / seed phrases (treat with extreme care),

- API keys in

.env, CI secrets, and config files.

Step 4 — Validate with behavior-based signals (not just string IOCs)

IOCs (domains, hashes) decay fast. Behavior sticks.

Look for:

- New outbound connections around the exact time you ran a “setup” command.

- Creation of archives (zip/7z) of user home directories, browser profiles, or wallet directories.

- Unusual access to keychain stores on macOS or credential stores on Windows.

- Persistence creation (launch agents, scheduled tasks, registry run keys).

Multiple news and research summaries emphasize the malware’s goal as data theft from local stores and credentials. (Notícias do Hacker)

6) Automatable auditing: how to scan installed skills safely

You want a repeatable way to answer three questions:

- What skills are installed?

- Which contain suspicious “setup” patterns?

- Which fetch or execute remote content?

6.1 Quick scan for risky instruction patterns (safe, non-exploit)

This command searches for common high-risk markers (encoding/obfuscation and “download-then-execute” patterns) across your local skills directory.

# Defensive scan: find suspicious patterns in skill docs and scripts

# Usage: ./scan_skills.sh /path/to/skills

set -euo pipefail

SKILLS_DIR="${1:-./skills}"

# ripgrep is fast and safe for content search

rg -n --hidden --no-ignore \\

-e 'base64\\s+(-d|--decode| -D)\\b' \\

-e '\\b(powershell|pwsh)\\b.*\\b-enc(odedcommand)?\\b' \\

-e '\\b(curl|wget)\\b.*\\|\\s*(bash|sh|zsh)\\b' \\

-e '\\b(source|\\. )\\s+<(curl|wget)\\b' \\

-e '\\b(prereq|prerequisite|install|setup)\\b.*\\b(command|terminal|run)\\b' \\

"$SKILLS_DIR" || true

Why this matters: ecosystem analyses describe malicious skills leveraging obfuscated commands and staged script execution; scanning for these markers is a low-effort way to surface high-risk candidates for manual review. (Médio)

6.2 JSON/YAML skill inventory + risk scoring (defender-friendly Python)

This script doesn’t try to “detect malware.” It does something more useful: it inventories skills, extracts text, flags risky patterns, and outputs a sortable report you can commit into your security workflow.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Defensive skill inventory & heuristic scanner.

- Lists skill folders

- Scans SKILL.md and common manifest files

- Flags risky patterns (encoding, download+execute, opaque installers)

Outputs: CSV report for review / ticketing.

This is intentionally heuristic and safe: it does NOT download anything.

"""

import csv

import os

import re

from pathlib import Path

RISK_PATTERNS = {

"base64_decode": re.compile(r"\\bbase64\\b.*\\b(-d|--decode| -D)\\b", re.I),

"powershell_encoded": re.compile(r"\\b(powershell|pwsh)\\b.*\\b-enc(odedcommand)?\\b", re.I),

"curl_pipe_shell": re.compile(r"\\b(curl|wget)\\b.*\\|\\s*(bash|sh|zsh)\\b", re.I),

"source_remote": re.compile(r"\\b(source|\\. )\\s+<\\((curl|wget)\\b", re.I),

"installer_language": re.compile(r"\\b(prereq|prerequisite|install|setup)\\b.*\\b(run|command|terminal)\\b", re.I),

"opaque_blob": re.compile(r"[A-Za-z0-9+/]{200,}={0,2}"), # long base64-ish blobs

}

TARGET_FILES = [

"SKILL.md",

"skill.md",

"README.md",

"readme.md",

"manifest.json",

"skill.json",

"skill.yaml",

"skill.yml",

]

def read_text(p: Path) -> str:

try:

return p.read_text(errors="ignore")

except Exception:

return ""

def scan_text(text: str) -> list[str]:

hits = []

for name, rx in RISK_PATTERNS.items():

if rx.search(text):

hits.append(name)

return hits

def main(root: str):

root_path = Path(root).expanduser().resolve()

rows = []

for dirpath, dirnames, filenames in os.walk(root_path):

d = Path(dirpath)

# Treat each folder containing SKILL.md as a skill folder

if "SKILL.md" not in filenames and "skill.md" not in filenames:

continue

combined = ""

present_files = []

for fn in TARGET_FILES:

p = d / fn

if p.exists() and p.is_file():

present_files.append(fn)

combined += "\\n\\n" + read_text(p)

hits = scan_text(combined)

rows.append({

"skill_path": str(d),

"files_seen": ",".join(present_files),

"risk_hits": ",".join(hits) if hits else "",

"risk_score": len(hits),

})

rows.sort(key=lambda r: r["risk_score"], reverse=True)

out = "openclaw_skill_audit.csv"

with open(out, "w", newline="", encoding="utf-8") as f:

w = csv.DictWriter(f, fieldnames=["skill_path", "files_seen", "risk_hits", "risk_score"])

w.writeheader()

w.writerows(rows)

print(f"[+] Wrote {out} with {len(rows)} skill folders")

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

main(sys.argv[1] if len(sys.argv) > 1 else "./skills")

This aligns with how defenders should approach the problem: the most consistent early signal in reporting is the presence of suspicious setup patterns and remote execution guidance embedded in skill content. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

7) IOC thinking that survives a week: shift from strings to behaviors

Security teams often ask for “the list of malicious hashes and domains.” In these incidents, that’s necessary—but not sufficient—because campaigns iterate quickly. What lasts longer are tactics that reflect the attacker’s constraints:

Durable behavioral indicators

- New network destinations immediately after a skill “install/setup” step If a setup step triggers connections to unfamiliar hosts, treat as high-risk.

- Encoded or obfuscated one-liners in setup instructions Base64 and encoded PowerShell frequently show up when attackers want to reduce readability. (Médio)

- “Download and execute” patterns Whether it’s a direct pipe to shell or a staged download, the invariant is: remote content becomes code. (Snyk)

- Credential store access from non-standard processes macOS keychain prompts or suspicious access attempts, browser profile scraping, wallet directory reads.

- Archive creation + outbound transfer Zipping profile folders then pushing them out is a common infostealer shape.

A practical table for ops

| Sinal | Por que é importante | Where to log | What to do first |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obfuscated setup commands in skill docs | Strong predictor of malicious intent | Repo/FS scans, PR reviews | Quarantine skill; block outbound; review changes |

| Outbound traffic during “setup” | Often staging or exfil | EDR net telemetry, firewall logs | Capture destination; isolate host; rotate secrets |

| Unexpected access to browser/Keychain | Infostealer behavior | EDR process telemetry | Incident response workflow; credential reset |

| New persistence entry | Long-term control | OS logs, EDR | Remove persistence; reimage if needed |

8) The broader supply-chain lesson: compare to headline CVEs without confusing the story

It’s tempting to say, “This is like Log4Shell.” It isn’t—at least not mechanically. But the reason those CVEs became watershed moments is relevant: they taught organizations to treat ecosystems as part of their perimeter.

CVE-2024-3094 (XZ Utils / liblzma): upstream trust can be poisoned

NIST’s summary of CVE-2024-3094 describes malicious code introduced into upstream tarballs and activated through an obfuscated build process, resulting in a modified library that can affect downstream software linked against it. (NVD)

The parallel isn’t “same exploit.” It’s the trust-chain reality: if the upstream distribution point is compromised, your downstream controls must include verification and provenance—not just vulnerability scanning.

CVE-2021-44228 (Log4Shell): input surfaces become execution surfaces

NVD’s description of CVE-2021-44228 explains how attacker-controlled data could lead to code execution through JNDI lookups under certain configurations. (NVD)

The parallel here is conceptual: data and instructions can blur into an execution trigger. In the OpenClaw skill ecosystem, SKILL.md and other content channels can play a similar “execution-adjacent” role—especially when humans (or agents) follow instructions without verification.

CVE-2020-10148 (SolarWinds Orion API auth bypass): platform compromise amplifies downstream risk

NVD describes CVE-2020-10148 as an authentication bypass in SolarWinds Orion’s API that could enable remote attackers to execute API commands and compromise the instance. (NVD)

The useful lesson: when a platform is trusted to orchestrate actions broadly, a compromise becomes multiplicative. Agents are orchestration by design.

9) Defenses that actually work (and won’t die in committee)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: you will not “moderate” your way out of this with a few policy updates. You need a layered model that assumes malicious skills will occasionally bypass marketplace controls.

9.1 Treat skills like executable code, not like content

If your org currently allows developers to install skills the way they install browser extensions, flip the default:

- Skills must be reviewed like scripts.

- Skill sources must be pinned.

- New skill intake must run through a gate (at minimum: inventory + heuristic scan + sandbox test).

This isn’t paranoia; it’s the only defensible posture when skills can inherit agent privileges. (Snyk)

9.2 Build an allowlist and mirror approved skills

A pragmatic model looks like this:

- Create an internal “approved skills” repository.

- Only install from your internal mirror.

- Require code review for any change.

- Run automated scanning on every update (pattern scanning + secret scanning).

This is how you treat internal Terraform modules or CI templates; agent skills deserve the same governance.

9.3 Sandbox the agent environment (reduce blast radius)

You do not need a perfect sandbox to materially reduce risk. You need enough containment to make credential theft harder and exfil noisier:

- Run the agent as a dedicated OS user with minimal permissions.

- Limit filesystem scope (no blanket access to home directories by default).

- Restrict network egress (deny by default; allow only required domains).

- Store secrets in a vault with short-lived tokens; avoid plaintext

.envsprawl.

Ecosystem commentary emphasizes that skills can gain shell/file access; your response is to make that access narrower and less valuable. (Snyk)

9.4 Log the agent like you log an admin

If your agent can run commands, treat it as a privileged automation account:

- command execution logs

- network egress logs

- file access auditing for sensitive paths

- immutable logs for IR

9.5 Ban “paste this command” setups (or route them through verification)

A hard rule that works: no skill is allowed to require manual execution of obfuscated terminal commands. If a skill truly needs dependencies, it must declare them in a verifiable manifest and install them through a controlled mechanism—not by telling users to paste a blob into a shell.

This is not an ideological stance; it’s a pattern repeated across reporting and research analyses. (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

10) Governance: what marketplace controls help (and what they can’t do)

Some platform-side mitigations have been discussed publicly, including requiring contributor accounts to meet minimum age and adding reporting mechanisms. News coverage suggests these measures exist but are not sufficient on their own. (The Verge)

Marketplace controls that help:

- identity and reputation gating for publishers

- automated scanning for known bad patterns

- human review for popular skills

- transparent takedown logs and provenance metadata

Controls that do não solve the core issue:

- “Just warn users” banners

- relying on crowd reporting as the primary filter

- assuming “the agent will be smart enough not to run dangerous things”

The structural problem remains: if a skill can instruct execution, and users want convenience, attackers will keep exploiting that interface.

11) Incident response playbook (copy/paste runbook)

This is a practical runbook you can drop into your internal wiki.

11.1 Trigger conditions

Start this playbook if any of these occur:

- A new skill is installed from an untrusted source.

- A skill requires obfuscated terminal commands.

- EDR alerts on suspicious downloads or credential access after a skill install.

11.2 Containment steps (first hour)

- Quarantine host.

- Block suspicious outbound destinations at the edge.

- Capture volatile data (process list, net connections).

- Preserve skill directories and logs.

11.3 Eradication and recovery

- Remove unapproved skills.

- Remove persistence.

- Reimage if you can’t validate integrity quickly.

- Rotate secrets (treat as mandatory).

11.4 Post-incident hardening

- Add the skill patterns to your detection rules.

- Update intake policy (allowlist + mirror).

- Tighten agent sandbox and egress.

A real-world pain point in incidents like this isn’t “finding the first bad thing.” It’s proving to stakeholders that you’ve contained the blast radius and validated remediation—across many machines and many secrets—without turning your security team into a ticket factory.

In environments where teams already run repeatable security workflows (asset inventory → scan → evidence capture → report), an AI-assisted platform like Penligent can be used as an operational layer to standardize “verify, don’t just patch”: collecting host-level evidence, correlating findings, and producing a remediation report that’s consistent across projects.

Separately, if your organization treats agent ecosystems as part of its broader offensive/defensive readiness, Penligent-style automated testing workflows can also help you validate that egress controls, secret rotatione endpoint baselines behave as expected after containment—so your postmortem is anchored in proof, not assumptions.

(If you can’t deploy this credibly in your environment, skip this section; forced product tie-ins reduce trust.)

12) The bottom line: agents are now part of your supply chain

The OpenClaw / ClawHub poisoning wave is a clean warning shot: when you attach a marketplace of third-party “capabilities” to a tool that can read your files and run commands, your risk model changes. Multiple sources describe hundreds of malicious skills and infostealer delivery, and researchers emphasize that agent skills can operate with the agent’s privileges. (Koi)

The right default assumption going forward:

- Inventory what your agent can do.

- Constrain what it is allowed to touch.

- Verificar every third-party capability like code.

- Monitor execution and egress like you would for an admin.

- Rotate secrets fast when you’re unsure.

- Repeat until it’s boring.

If that sounds heavy, it’s because agents are not “apps.” They’re automation operators. And operators require operational security.

Recursos

- Incident reporting: CybersecurityNews.com coverage of OpenClaw / ClawHub supply-chain poisoning (Notícias sobre segurança cibernética)

- Research summary: The Hacker News on 341 malicious skills and cross-platform impact (Notícias do Hacker)

- Primary research: Koi Security on the ClawHavoc campaign and audit methodology (Koi)

- Ecosystem audit: Snyk “ToxicSkills” findings and defensive recommendations (Snyk)

- Risk framing: 1Password on agent skills as a new attack surface (1Password)

- Additional reporting: SC Media note on AMOS/keyloggers/backdoors in malicious skills (Mídia SC)

- Mainstream explainer: The Verge overview of why the model is risky (The Verge)

- CVE anchor: National Vulnerability Database on CVE-2024-3094 (XZ Utils supply-chain compromise) (NVD)

- CVE anchor: NVD on CVE-2021-44228 (Log4Shell) (NVD)

- CVE anchor: NVD on CVE-2020-10148 (SolarWinds Orion API auth bypass) (NVD)

- Additional analysis: Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 threat brief on CVE-2024-3094 lessons for supply-chain defense (Unit 42)

- Defensive FAQ: Tenable FAQ on CVE-2024-3094 context and mitigation thinking (Tenable®)

- OpenClaw hardening manifesto (post-mortem + architecture) (Penligente)

- Penligent HackingLabs category index (browse related OpenClaw / agent security pieces) (Penligente)