Why CVE-2025-49132 is not “just another panel bug”

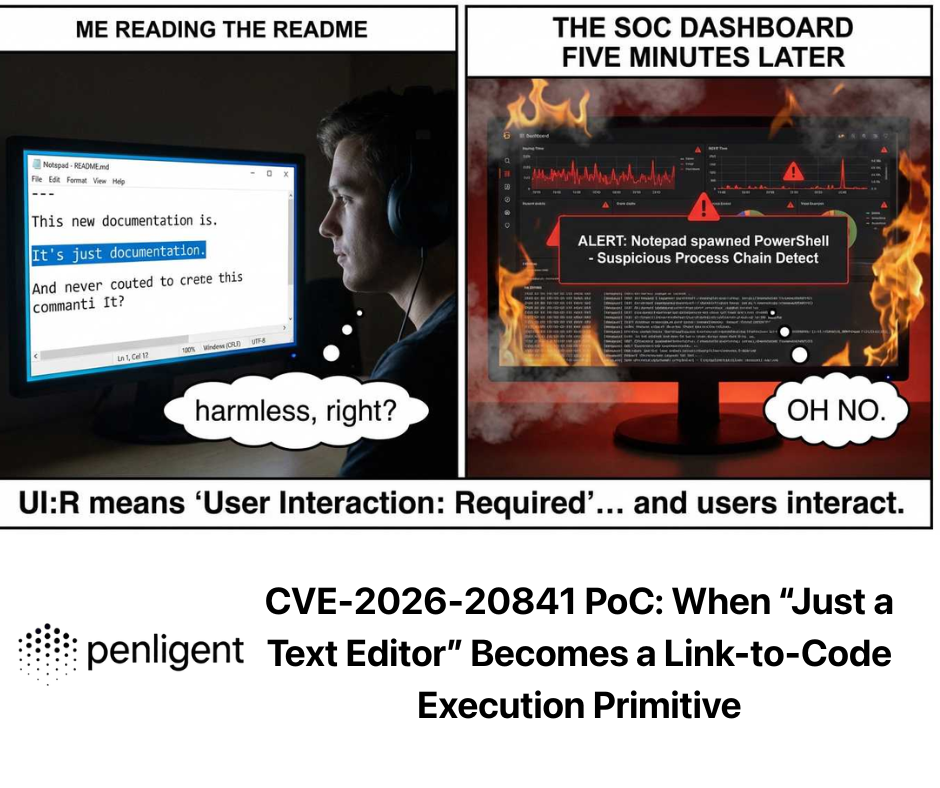

Every few years, defenders relearn the same lesson the hard way: the most dangerous execution surfaces aren’t always template engines or upload endpoints. Sometimes they’re the endpoints teams treat as “safe plumbing”—like localization, configuration, or metadata routes.

CVE-2025-49132 is exactly that kind of failure mode.

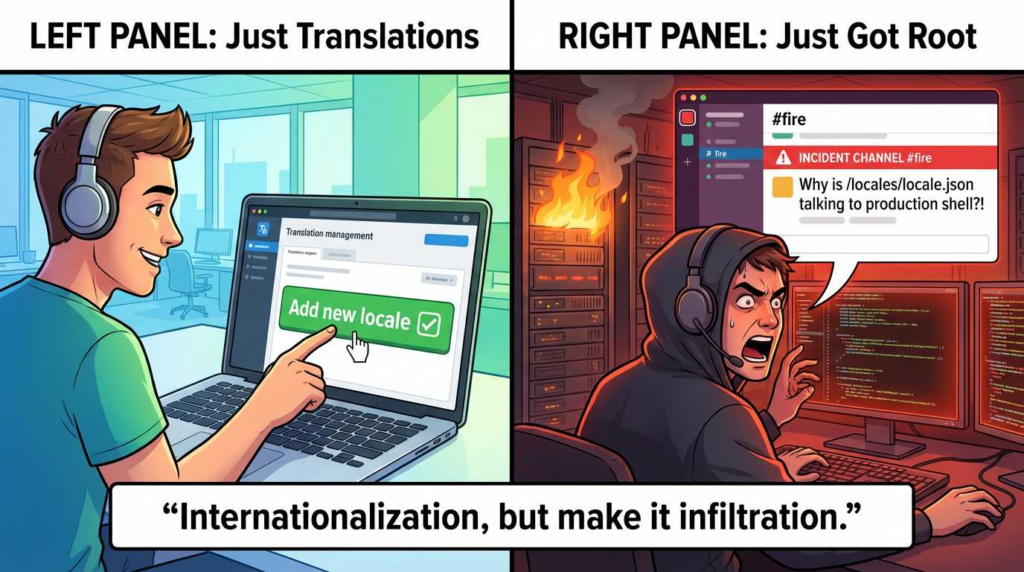

Per the National Vulnerability Database and the official GitHub security advisory, Pterodactyl Panel versions before 1.11.11 allow an attacker to execute arbitrary code without authentication by hitting /locales/locale.json with the locale e espaço de nome query parameters. (NVD)

That combination—pre-auth + RCE + internet-facing admin surface—is why this CVE belongs in the “drop everything” queue if you run Pterodactyl anywhere reachable from the public internet.

What the vulnerability enables

The vendor advisory doesn’t hedge: unauthenticated arbitrary code execution can be used to gain access to the panel server, read panel config secrets (including .env), extract sensitive data from the database, and access files of servers managed by the panel. (GitHub)

The NVD entry mirrors the same impact framing and the key technical detail: the vulnerable route and parameters (/locales/locale.json, locale, espaço de nome) and the fixed version (1.11.11). (NVD)

If you’re trying to explain urgency internally, say it like this:

- É remote, no-logine code execution.

- It targets a component (the panel) that commonly sits next to credentials, databases, and management capability.

- Once the panel host is compromised, you’re no longer dealing with “a web bug”—you’re dealing with environment compromise.

The “search intent” checklist: what engineers want answered immediately

When people search cve-2025-49132, they’re usually looking for fast, verifiable answers:

- Am I affected?

- What’s the fastest safe mitigation?

- What version fixes it?

- How do I prove the fix (not just claim it)?

- How do I detect scanning/exploitation attempts at scale?

This article follows that order.

Affected scope and fixed version

- Affected: Pterodactyl Panel < 1.11.11

- Fixed: 1.11.11

- Attack surface:

/locales/locale.jsoncomlocaleeespaço de nomequery parameters (NVD)

If you have multiple environments (prod/stage/labs) or multiple regions, assume you have at least one forgotten instance until you prove otherwise.

Prioritization signals: how to justify “this week” remediation

A quick prioritization table you can drop into an internal ticket:

| Sinal | What to look for | Por que é importante | Evidências |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-auth RCE | No credentials required | Highest urgency class for internet-facing apps | Vendor + NVD describe unauthenticated arbitrary code execution (NVD) |

| Public exploit ecosystem | Public PoCs / scanning templates | “Will be scanned” becomes the default | Public Nuclei template exists (GitHub) |

| EPSS (probability signal) | High EPSS & high percentile | Strong indicator of near-term exploitation activity | EPSS ~35% and ~97th percentile reported in multiple places (GitHub) |

Important nuance: EPSS is not a guarantee of compromise; it’s a probabilistic prioritization signal. But when it lines up with pre-auth RCE and a public scanning template, it’s enough to move the CVE to the top.

Step 1 — Inventory: find every instance that could be exposed

This is where most teams lose time. Not because remediation is hard, but because “how many panels do we have?” turns into archaeology.

Uso three independent views and reconcile them:

A) Deployment reality

- Container registry: images and tags referencing Pterodactyl Panel

- IaC manifests: Terraform/Helm/Ansible

- CMDB (if you’re lucky)

B) Internet reality

- DNS records and historical subdomains

- Reverse proxies you forgot about

- “Temporary” staging environments that never died

C) Log reality

- Requests to

/locales/locale.json - Spikes in 4xx/5xx around that path

If you can’t reconcile A/B/C, treat the environment as exposed until proven otherwise.

Step 2 — Immediate mitigations

Upgrade is the real fix. But if you need a same-day stopgap while you coordinate deployments, you can reduce risk by constraining the vulnerable route at the edge.

Option A: Temporarily block /locales/locale.json at the web server / reverse proxy

This can break localization behavior, so it’s not a forever solution—but it is a legitimate emergency control. The vendor advisory notes a web-server-level disablement as a workaround. (GitHub)

Nginx example (copy-paste):

location = /locales/locale.json {

return 403;

}

If you must keep it reachable for business reasons, you can at least restrict it:

location = /locales/locale.json {

# Allow only internal networks (example)

allow 10.0.0.0/8;

allow 192.168.0.0/16;

deny all;

}

Option B: Put an external WAF in front of it (short-term)

The advisory discusses external WAF mitigation as an option. (GitHub)

A WAF is not a substitute for upgrading, but it can buy you time while you roll a controlled patch across environments.

Step 3 — The real fix: upgrade to 1.11.11

The only clean closure is upgrading all affected instances to 1.11.11. (NVD)

Treat the upgrade as an incident response change, not a casual patch:

- Record the instance list (asset IDs / domains)

- Record antes de e after versions

- Capture rollout completion evidence (all replicas / all regions)

- Document rollback plan (but do not roll back to a vulnerable version)

Step 4 — Prove-the-fix verification

“Upgraded” is not a security state. It’s a claim.

A provable fix means you can show evidências in three categories:

1) Version evidence

- Deployed version is 1.11.11 everywhere that was exposed

- No old images remain in active use

- No forgotten staging domains still point at old hosts

2) Behavior evidence (non-weaponized)

You’re not trying to reproduce an exploit; you’re trying to confirm that the endpoint no longer accepts risky behavior and that request handling is hardened.

A safe, conservative check is: request the endpoint and observe status codes, caching behavior, and error handling consistency.

Python “conservative probe” (does not attempt exploitation):

import requests

from urllib.parse import urljoin

def probe(base_url: str, timeout=8):

url = urljoin(base_url.rstrip("/") + "/", "locales/locale.json")

r = requests.get(url, timeout=timeout, allow_redirects=False)

return {

"url": url,

"status": r.status_code,

"content_type": r.headers.get("content-type", ""),

"bytes": len(r.content),

"server": r.headers.get("server", ""),

}

targets = [

"<https://panel.example.com>",

# add all discovered instances

]

for t in targets:

print(probe(t))

This doesn’t prove “no vulnerability” on its own—but it turns unknown exposure into measurable surface data you can trend over time.

3) Scan evidence

Public scanning templates exist for this CVE, including a Nuclei template in ProjectDiscovery’s nuclei-templates repository. (GitHub)

Run your own scanning in a controlled way (internal policy permitting), and attach scan results to the closure record.

Step 5 — Detection: alert on patterns, not payloads

You don’t need to build detections around exploit strings. You need to detect intenção e behavior, especially because payloads mutate quickly.

What to log and alert on immediately

Primary signal:

- Requests to

/locales/locale.jsonwith bothlocale=enamespace=(These are explicitly called out as the parameters used in exploitation.) (GitHub)

Secondary signals:

- Bursts (rate anomalies) from a single IP

- Multi-host sweeps (same IP hitting multiple domains)

- Unusual UA patterns (empty UA, obvious scanners)

- Spikes in 403/400/500 around the endpoint

Quick log triage (Nginx combined logs)

# 1) Pull all hits to the endpoint

grep -E ' /locales/locale\\.json' /var/log/nginx/access.log > locale_hits.log

# 2) Focus on requests with BOTH locale and namespace parameters

grep -E 'locale=.*namespace=|namespace=.*locale=' locale_hits.log > locale_risky.log

# 3) Top source IPs

awk '{print $1}' locale_risky.log | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head -n 20

What “good” looks like after mitigation

- Your block/allow policy results in stable, expected 403/401 patterns (if you blocked it)

- No sustained bursts to the endpoint

- No repeated parameter-variation probing from the same source

If you suspect compromise: the minimum viable containment sequence

Because the advisory explicitly warns about reading secrets and database extraction, assume secrets could be exposed if exploitation occurred. (GitHub)

Containment and recovery, in order:

- Stop further access

- Block the endpoint at the edge or take the panel off the public internet.

- Preserve evidence

- Reverse proxy logs, app logs, container runtime events, deployment history.

- Rotate secrets

- Panel secrets (

.env), database creds, SMTP creds, object storage keys, third-party API tokens.

- Panel secrets (

- Check for persistence

- New admin accounts, new tokens, modified startup scripts, cron jobs, unauthorized changes.

- Rebuild if needed

- If you can’t establish integrity, rebuild from known-good images and rehydrate configs with rotated secrets.

The broader lesson: “resource loaders” are an execution surface now

CVE-2025-49132 is a reminder that modern platforms add dynamic loaders everywhere: language packs, plugin registries, “namespace” routing, content packs, feature flags. Those are often built for convenience, not adversarial pressure.

Defenders should treat any endpoint that:

- selects a resource by user-controlled name,

- resolves a path or namespace dynamically, or

- interprets content server-side,

as part of the execution surface, even if it looks like harmless UI support.

If your pain isn’t “patch a single host,” but “close this across a fleet and prove it to everyone who asks,” the most expensive part of CVE response is usually the fluxo de trabalho: asset discovery, verification, evidence, and repeatability.

That’s where Penligent focuses in its CVE-2025-49132 write-up—turning “patch and pray” into “patch and prove,” emphasizing verifiable closure and operational checks you can attach to an incident record. (Penligente)

In practice, that means you build a reusable task that: finds exposed instances, validates patch state, re-checks the risky route behavior, and produces a short evidence bundle your team can file and audit—so the next time a panel-class pre-auth RCE lands, you don’t reinvent the process under pressure.

Referências

- NVD entry for CVE-2025-49132 (affected versions, endpoint, impact). (NVD)

- Vendor advisory (impact details, parameters, mitigation notes). (GitHub)

- GitHub advisory page (EPSS context and CWE mapping). (GitHub)

- Nuclei template (automation signal for scanning at scale). (GitHub)

- EPSS probability signal (risk prioritization context). (wiz.io)

- Penligent’s CVE-2025-49132 “prove the fix” article (internal link). (Penligente)