Why this CVE matters more than it looks

Security teams have a long memory for the “small” components that turned into big incidents: a viewer that became an execution surface, a file association that became a lateral movement enabler, a convenience feature that quietly bypassed an expectation like Mark-of-the-Web warnings or “are you sure?” prompts.

CVE-2026-20841 lands squarely in that lineage.

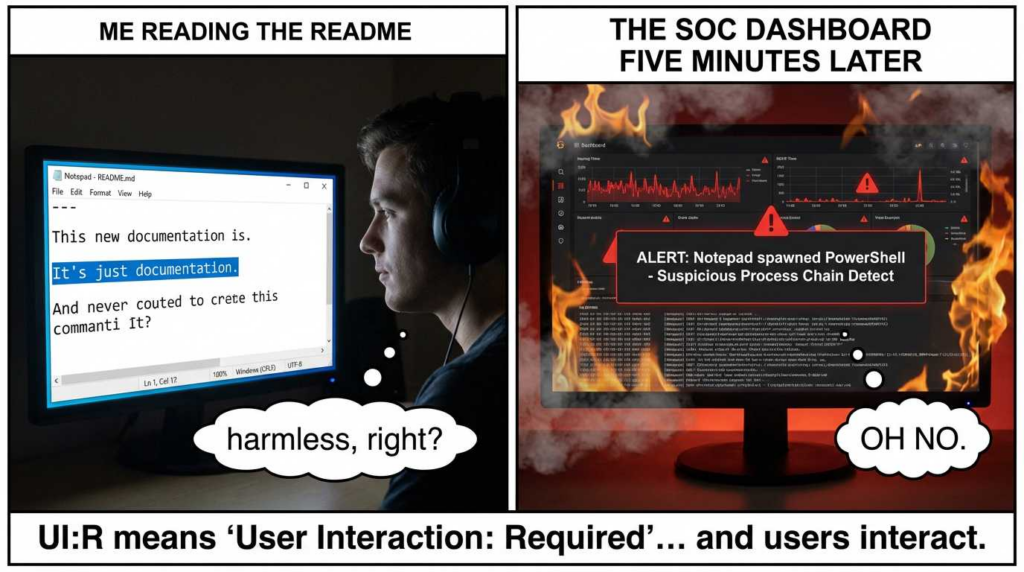

It’s a high-severity vulnerability in the modern Windows Notepad app (the Microsoft Store–distributed Notepad, not the legacy classic Notepad.exe). It was assigned a CVSS 3.1 base score of 8.8 with a vector requiring user interaction (UI:R), but otherwise low friction (AV:N/AC:L/PR:N). (NVD) The practical abuse story is straightforward: a user opens a Markdown file in Notepad, clicks a malicious link, and Notepad launches an unverified protocol in a way that can result in code execution in the user’s context. (헬프넷 보안)

No kernel exploit. No macro. No “disable AMSI.” Just a file, a click, and a trust boundary that didn’t hold.

What makes this worth a long, defensive playbook is not only the specific Notepad bug. It’s the repeatable pattern:

Document/markup → link rendering → protocol handler invocation → remote/local payload execution

…often with confusing UX and inconsistent warning surfaces.

If you treat CVE-2026-20841 as a one-off patch item, you’ll close the ticket but keep the class of risk alive in your estate.

The verified facts

Affected product scope

- The issue affects the Windows Notepad App (Store-based Notepad). (NVD)

- Reporting around the patch indicates it impacts Notepad versions prior to 11.2510, with the fix rolling out in the February 2026 Patch Tuesday window. (Windows Central)

Vulnerability class and CVSS

- NVD classifies it as CWE-77 (Command Injection) and records the CVSS v3.1 vector AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:R/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H. (NVD)

- MSRC’s description (as quoted in multiple write-ups) describes tricking a user into clicking a malicious link in a Markdown file opened in Notepad, leading to launching unverified protocols that load/execute remote files in the user’s context. (헬프넷 보안)

“Remote vs local” nuance (don’t get tripped up)

NVD’s change history shows Microsoft modified wording from “execute code over a network” to “execute code locally,” even while the CVSS vector remains AV:N and the practical scenario still involves a network-delivered lure (file delivery) plus interaction. (NVD)

Treat this as a common taxonomy mismatch: exploitation can be initiated via network content delivery and protocol handlers, but the final execution occurs on the endpoint in the user context.

User experience / warning surface

One of the scarier parts in common reporting is that certain link execution paths may occur without typical Windows security warnings (depending on protocol and handler behavior), which changes user expectations and SOC triage. (컴퓨터)

The attack chain: how CVE-2026-20841 gets used in the real world

Below is a realistic, defense-focused chain that aligns with reported behavior without turning into an exploitation recipe:

- Initial delivery (low sophistication)

- Phish attachment (

.md), ZIP with README, Teams/Slack file share, Git repo contribution, ticketing attachment, or “documentation pack” sent to engineers.

- Phish attachment (

- Open in Notepad

- Notepad’s Markdown rendering encourages users to treat the file like a previewable doc rather than raw text.

- Click the link

- The attacker’s goal is the click, not a parser crash.

- Protocol handler misuse

- Notepad launches a protocol / handler path that is “allowed” but shouldn’t be trusted from a Markdown context.

- Payload execution in user context

- Execution inherits the current user’s privileges. That matters because:

- Dev machines often have local admin.

- Build agents can have token-bearing sessions.

- IT/Sec users often have elevated tools installed.

- Execution inherits the current user’s privileges. That matters because:

This is why “UI:R” does not mean “low risk.” It means the attacker optimizes for convincing UX.

Who is most at risk

1) Developer workstations and build-adjacent endpoints

Engineers open Markdown constantly: READMEs, runbooks, internal docs, third-party tool instructions. A malicious .md looks normal.

2) Helpdesk / IT endpoints

IT staff open docs from vendors, customers, and internal KB exports all day. They also often have elevated tools.

3) SOC and IR endpoints

Analysts open case artifacts, threat intel notes, and “investigation summaries.” If your SOC opens untrusted Markdown, you want strong isolation.

4) Organizations with constrained Store updates

Any org that disables or delays Microsoft Store app updates (or has inconsistent Store connectivity) can get stuck on vulnerable app versions—especially for inbox-like Store apps.

What you should do immediately

Step 1: Confirm exposure (Notepad version inventory)

You want to identify endpoints running a vulnerable Notepad App version (pre-fix).

PowerShell inventory idea (endpoint or remote session):

# List Notepad package and version (Store app)

Get-AppxPackage -AllUsers Microsoft.WindowsNotepad | Select-Object Name, Version, PackageFullName

# If you manage via winget, also record winget metadata (optional)

winget list --id Microsoft.WindowsNotepad

Why this matters: it gives you a deterministic “is vulnerable / is patched” control for compliance reporting.

Step 2: Force/enable Store app updating (where appropriate)

Microsoft’s own Intune guidance highlights policy controls for Store app auto-updates, including ApplicationManagement/AllowAppStoreAutoUpdate and the Settings Catalog equivalent (“Allow apps from the Microsoft app store to auto update”). (Microsoft Learn)

If your environment prevents auto-updates, you may be unintentionally freezing vulnerable Store apps in place.

Step 3: Reduce click-to-execution blast radius

Even patched, you still want layered controls because the 클래스 of issue will recur (in Notepad or in the next “viewer” feature).

Minimum viable hardening:

- Ensure Microsoft Defender Antivirus real-time protection and cloud-delivered protection are enabled (ASR rules depend on Defender being primary). (Microsoft Learn)

- Deploy an “Internet file caution” posture:

- SmartScreen enabled

- Strong browser download policies

- MOTW preserved (don’t strip Zone.Identifier)

Step 4: Add detection now (because the patch isn’t instantly everywhere)

Your SOC needs alerting that spots:

- Notepad spawning unusual processes

- Protocol handler launches immediately after Notepad interaction

- New executable creation followed by execution tied to Notepad context

The rest of this guide gives you production-ready detection content.

Technical risk analysis: why Markdown link handling is a security boundary

Markdown rendering converts “plain text” into a semi-interactive surface:

- It introduces clickable links

- It encourages users to treat content as trusted documentation

- It creates a bridge between file content and system-level handlers (protocols, file associations, shell execution)

Once a local app becomes a “launcher,” it inherits all the risk of:

- protocol handler ambiguity

- shell execution rules

- warning prompt inconsistencies

- “living off the land” payloads invoked via built-in handlers

This is the same reason many “viewer” products have historically been exploited: it’s not the file format; it’s the bridge from passive viewing to active invocation.

Detection engineering you can deploy today

What good detection looks like for CVE-2026-20841

You’re not hunting for “CVE-2026-20841” on endpoints. You’re hunting for a behavior cluster:

- Notepad opens a Markdown file (optional to detect directly)

- Notepad launches something it shouldn’t

- That something leads to payload execution, script execution또는 download-then-execute

So your detection should focus on:

- Process tree anomalies (parent/child relationships)

- Command-line patterns

- Network connections initiated by children of Notepad

- File creation followed by execution in short time windows

Sigma rule examples

Below are sample Sigma rules you can adapt. They’re intentionally written as “behavior-first,” because exact process names can vary by packaging, and different EDRs normalize fields differently.

Sigma 1 — Notepad spawns script engines or LOLBins

title: Suspicious Child Process Spawned by Windows Notepad (Possible Markdown Link Abuse)

id: 9f7f0d12-4a0d-4c51-9d2f-1e8cfcd44b21

status: experimental

description: Detects suspicious child processes spawned by Windows Notepad, consistent with click-to-execution abuse paths.

author: SOC Engineering

date: 2026/02/13

references:

- <https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-20841>

logsource:

category: process_creation

product: windows

detection:

selection_parent:

ParentImage|endswith:

- '\\notepad.exe'

selection_child_suspicious:

Image|endswith:

- '\\powershell.exe'

- '\\pwsh.exe'

- '\\cmd.exe'

- '\\wscript.exe'

- '\\cscript.exe'

- '\\mshta.exe'

- '\\rundll32.exe'

- '\\regsvr32.exe'

- '\\installutil.exe'

- '\\bitsadmin.exe'

- '\\certutil.exe'

condition: selection_parent and selection_child_suspicious

falsepositives:

- Rare legitimate admin workflows where Notepad is used to launch scripts (should be discouraged anyway)

level: high

tags:

- attack.execution

- attack.t1204

- cve.2026.20841

Sigma 2 — Notepad triggers URL/protocol handler launcher patterns

This one depends on how your telemetry captures protocol launches. Some environments see explorer.exe or a browser as the immediate child; others see helper processes.

title: Notepad-Initiated Protocol/URL Launch Followed by Execution

id: 4a1f0d2e-1cfe-4b8a-92fb-3a33b8b2c7a0

status: experimental

description: Correlates Notepad spawning or initiating URL/protocol launches that quickly lead to process execution.

author: SOC Engineering

date: 2026/02/13

logsource:

category: process_creation

product: windows

detection:

selection_parent:

ParentImage|endswith:

- '\\notepad.exe'

selection_child_launcher:

Image|endswith:

- '\\explorer.exe'

- '\\msedge.exe'

- '\\chrome.exe'

- '\\firefox.exe'

selection_cmdline_url:

CommandLine|contains:

- 'http://'

- 'https://'

- 'ms-'

- 'file://'

condition: selection_parent and selection_child_launcher and selection_cmdline_url

falsepositives:

- Users legitimately clicking documentation links in Notepad (tune via allowlists + correlation with downloads/execution)

level: medium

tags:

- attack.execution

- attack.t1204

- cve.2026.20841

How to tune Sigma effectively

- Add allowlists for common internal doc domains.

- Escalate severity only if you also observe:

- an executable created in Downloads/Temp

- script engine launch

- network egress to untrusted destinations

- subsequent Defender alert (SmartScreen/MDE)

Microsoft Defender XDR / MDE KQL hunting queries

These queries are written to be copy-paste starting points. Adjust for your environment’s naming and packaging behavior.

KQL 1 — Notepad spawning suspicious child processes

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "notepad.exe"

| where FileName in~ ("powershell.exe","pwsh.exe","cmd.exe","wscript.exe","cscript.exe","mshta.exe","rundll32.exe","regsvr32.exe","bitsadmin.exe","certutil.exe","installutil.exe")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName,

InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine,

FileName, ProcessCommandLine, FolderPath, SHA1

| order by Timestamp desc

Field references are documented in Microsoft’s schema for DeviceProcessEvents. (Microsoft Learn)

KQL 2 — Notepad → browser/explorer launch with URL/protocol indicators

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "notepad.exe"

| where FileName in~ ("explorer.exe","msedge.exe","chrome.exe","firefox.exe")

| where ProcessCommandLine has_any ("http://","https://","file://","ms-")

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName,

InitiatingProcessCommandLine, FileName, ProcessCommandLine

| order by Timestamp desc

KQL 3 — Correlate Notepad-driven execution with recent file creation

This helps surface “download then execute” chains by correlating process events to file events.

let timeWindow = 10m;

let suspiciousChildren =

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "notepad.exe"

| where FileName in~ ("powershell.exe","pwsh.exe","cmd.exe","wscript.exe","cscript.exe","mshta.exe","rundll32.exe","regsvr32.exe")

| project ChildTime=Timestamp, DeviceId, DeviceName, AccountName,

ChildProc=FileName, ChildCmd=ProcessCommandLine,

InitiatingCmd=InitiatingProcessCommandLine;

DeviceFileEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| where ActionType in~ ("FileCreated","FileModified")

| where FolderPath has_any ("\\\\Downloads\\\\","\\\\Temp\\\\","\\\\AppData\\\\Local\\\\Temp\\\\")

| project FileTime=Timestamp, DeviceId, FileName, FolderPath, SHA1

| join kind=innerunique suspiciousChildren on DeviceId

| where FileTime between (ChildTime - timeWindow .. ChildTime + timeWindow)

| project ChildTime, FileTime, DeviceName, AccountName,

ChildProc, ChildCmd, FileName, FolderPath, SHA1, InitiatingCmd

| order by ChildTime desc

DeviceFileEvents is the right table for file creation/modification context. (Microsoft Learn)

KQL 4 — Hunt for Notepad-driven network connections (child process egress)

If you’re correlating to network activity, union with DeviceNetworkEvents (pattern shown in Microsoft’s KQL guidance). (Microsoft Learn)

let suspiciousProc =

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| where InitiatingProcessFileName =~ "notepad.exe"

| project DeviceId, DeviceName, AccountName,

ProcTime=Timestamp, ProcId=ProcessId,

ProcName=FileName, ProcCmd=ProcessCommandLine;

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(14d)

| join kind=innerunique suspiciousProc on DeviceId

| where Timestamp between (ProcTime .. ProcTime + 15m)

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, AccountName,

ProcName, ProcCmd, RemoteUrl, RemoteIP, RemotePort, Protocol

| order by Timestamp desc

Intune / MDM configuration templates

This section is written for the “I need an actual template” use case—what to set, why to set it, and how to roll it out safely.

A. Ensure Store apps (including Notepad) can auto-update

Microsoft’s Intune documentation explicitly maps the policy:

- CSP:

ApplicationManagement/AllowAppStoreAutoUpdate - Settings Catalog path: Microsoft App Store → “Allow apps from the Microsoft app store to auto update” (Microsoft Learn)

Recommended baseline

- Set auto-update to Enabled (or at least do not block it), unless you have a controlled packaging pipeline that guarantees rapid rollout of Store app security fixes. (Microsoft Learn)

Intune Settings Catalog template (human-readable)

- Profile type: Windows 10 and later → Settings catalog

- Category: Microsoft App Store

- Setting: Allow apps from the Microsoft app store to auto update

- Value: Enabled

MDM Custom OMA-URI template (for the same control)

(Use this when you must push via Custom profile or a non-Settings Catalog approach.)

Name: Allow Microsoft Store app auto-updates

OMA-URI: ./Device/Vendor/MSFT/Policy/Config/ApplicationManagement/AllowAppStoreAutoUpdate

Data type: Integer

Value: 1

(Exact behavior/values should follow the Microsoft policy mapping for your tenant; the key point is the CSP mapping is authoritative.) (Microsoft Learn)

Operational note: If you previously blocked Store auto-updates via GPO (“Turn off Automatic Download and Install of updates”), it can effectively prevent required app updates. (Microsoft Learn)

B. Attack Surface Reduction (ASR) rules to reduce click-to-execution fallout

ASR rules don’t “patch Notepad,” but they meaningfully reduce the ability for a click-triggered chain to turn into a working execution path. Microsoft documents how to enable ASR rules and provides rule GUID references. (Microsoft Learn)

Suggested ASR baseline for this incident class

- Block executable content from email client and webmail

- Block Office apps from creating child processes (not directly Notepad, but strongly reduces common second-stage patterns)

- Block JavaScript or VBScript from launching downloaded executable content (especially relevant to “doc link → script → payload”)

- Block abuse of exploited vulnerable signed drivers (not specific, but strong posture)

Microsoft’s ASR references include GUID matrices and mode options. (Microsoft Learn)

Intune deployment path (recommended)

- Endpoint security → Attack surface reduction → Create Policy

- Profile: Attack surface reduction rules

- Set initial mode to Audit for 7–14 days where you have high developer tool density, then move critical rules to 블록 after tuning. Microsoft explicitly recommends audit mode to understand impact before enforcement. (Microsoft Learn)

MDM/PowerShell deployment (template)

Microsoft documents Set-MpPreference / Add-MpPreference commands for enabling ASR rules by GUID. (Microsoft Learn)

Example scaffold:

# Example: enable an ASR rule (replace <rule-guid> with the desired rule ID)

Add-MpPreference -AttackSurfaceReductionRules_Ids <rule-guid> -AttackSurfaceReductionRules_Actions Enabled

# Audit mode variant

Add-MpPreference -AttackSurfaceReductionRules_Ids <rule-guid> -AttackSurfaceReductionRules_Actions AuditMode

# Get current settings (useful before changes)

Get-MpPreference | Select-Object -ExpandProperty AttackSurfaceReductionRules_Ids

C. ASR exclusions (when business apps break)

If you must exclude paths (common in dev-heavy orgs), Microsoft documents the exclusion mechanism and warns that exclusions can severely reduce protection. (Microsoft Learn)

MDM CSP for ASR-only exclusions:

OMA-URI: ./Vendor/MSFT/Policy/Config/Defender/AttackSurfaceReductionOnlyExclusions

Keep exclusions narrow, temporary, and reviewed.

D. Windows Notepad App update enforcement via Intune remediation (operational template)

If you cannot rely on Store auto-updates alone (air-gapped, proxy-restricted, or Store disabled), you’ll want an Intune remediation script that:

- checks Notepad package version

- triggers Store update mechanism or fails compliance

High-level example pattern (pseudo-operational):

$pkg = Get-AppxPackage -AllUsers Microsoft.WindowsNotepad

if (-not $pkg) { exit 0 } # Not installed

$ver = [version]$pkg.Version

$minSafe = [version]"11.2510.0.0" # adjust based on your validated safe build

if ($ver -lt $minSafe) {

Write-Output "Vulnerable Notepad version detected: $ver"

exit 1

}

Write-Output "Notepad version OK: $ver"

exit 0

(Use your validated “safe” threshold based on what your tenant actually deployed; the public reporting indicates pre-11.2510 is vulnerable.) (Windows Central)

Patching strategy that actually works in enterprises

The mistake: “Patch Tuesday applied, we’re done”

For Store apps, “Patch Tuesday” does not guarantee every endpoint immediately updates the Store-delivered Notepad app—especially in:

- VDIs with restricted Store

- endpoints with Store blocked by policy

- devices that are rarely online

- environments with update deferrals or broken Store connectivity

A better strategy: “Prove patched”

Make patch status measurable:

Minimum metrics

- % endpoints with Notepad ≥ your safe version

- time-to-remediate for newly found vulnerable endpoints

- top segments failing updates (device rings, geography, network profiles)

유효성 검사

- Inventory by Appx package version (authoritative)

- Confirm policy posture (Store auto-update allowed)

- Confirm MDE telemetry shows version convergence (optional)

“Related CVEs” worth mentioning

CVE-2026-20841 is a Notepad-specific instance of a broader “content-to-execution” reality. Your org should treat these as linked risks:

- Office/OLE and link-based exploitation chains: the ecosystem repeatedly demonstrates that “content containers” become execution surfaces (see Microsoft-focused emergency patch narratives across the industry).

- High-impact Windows RCE families like EternalBlue-era thinking still matters because the remediation lesson is the same: don’t just patch—verify and reduce blast radius.

If you want an internal knowledge base that teaches engineers how to 증명 they’re not exposed (not just “install updates”), invest in playbooks that combine:

- version verification

- segmentation

- hardening controls

- detection that spots exploit primitives even when the specific CVE changes

If your organization uses (or is evaluating) 펜리전트 as an AI-assisted pentesting and verification workflow, CVE-2026-20841 is a clean example of a recurring need: fast validation + repeatable proof.

Two practical, non-forced ways it can help:

- Automated verification tasks for endpoint posture

- Generate “prove we’re patched” checks for Notepad versions across your fleet.

- Turn ad-hoc patch validation into a repeatable control with exportable evidence for audits.

- Playbook-driven detection and response validation

- Convert incident learnings into a reusable workflow: “detect suspicious Notepad child process spawns,” “hunt KQL,” “confirm ASR policy posture,” “verify Store auto-update policy,” and “report compliance gaps.”

If you don’t manage endpoint security or the Notepad surface isn’t relevant to your environment, skip the tool talk—this CVE is still a useful case study for link-to-execution surfaces.

Appendix A — Quick triage checklist (SOC-ready)

| Question | Evidence source | What “good” looks like |

|---|---|---|

| Are we exposed? | Appx Notepad version inventory | Majority at/above safe build; stragglers tracked |

| Are updates flowing? | Intune policy + device compliance | Store auto-update enabled or managed alternative |

| Is click-to-exec reduced? | ASR posture + audit logs | High-value ASR rules enabled (audit→block) |

| Are we detecting attempts? | MDE alerts + KQL hunts + Sigma | Alerts on Notepad child-process anomalies |

| Can we prove closure? | Report with counts + timestamps | “Patched %” + “Hunt results” + “policy state” |

Appendix B

- The Verge — Microsoft fixes Notepad flaw that could trick users into clicking malicious Markdown links

https://www.theverge.com/tech/877295/microsoft-notepad-markdown-security-vulnerability-remote-code-execution - Windows Central — Notepad’s new Markdown feature added a severe vulnerability that’s now patched

https://www.windowscentral.com/microsoft/windows/notepad-markdown-vulnerability-patched - PC Gamer — Notepad feature expansion and a high-severity vulnerability

https://www.pcgamer.com/software/windows/thanks-to-microsoft-adding-all-those-extra-features-to-notepad-it-now-unfortunately-sports-one-more-an-exploitation-vulnerability-with-a-high-security-rating/ - Windows Central — Windows 11 changes around Microsoft Store app update controls

https://www.windowscentral.com/microsoft/windows-11/microsoft-quietly-removes-ability-to-permanently-stop-apps-from-automatically-updating-on-windows-11-just-like-system-updates - TechRadar — Windows 11 now forcibly updates apps from the Microsoft Store (context on update behavior)

https://www.techradar.com/computing/windows/windows-11-now-forcibly-updates-apps-from-the-microsoft-store-and-not-everyone-is-happy

- CVE-2026-1868 GitLab AI Gateway RCE — The Anatomy of an AI Breach

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-1868-gitlab-ai-gateway-rce-the-anatomy-of-an-ai-breach/ - EternalBlue CVE, Finally Explained: MS17-010, the CVE Family, and How to Prove You’re Not Exposed

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/eternalblue-cve-finally-explained-ms17-010-the-cve-family-and-how-to-prove-youre-not-exposed/ - Beyond the Patch: Deep Analysis of CVE-2026-21509 and OLE Mitigation Bypasses

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/beyond-the-patch-deep-analysis-of-cve-2026-21509-and-ole-mitigation-bypasses/ - OpenClaw Multi-User Session Isolation Failure Authorization Bypass and Privilege Escalation

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/openclaw-multi-user-session-isolation-failure-authorization-bypass-and-privilege-escalation/ - CVE 2026 The Vulnerability Landscape: When Identity Breaks and Legacy Code Bites Back

https://www.penligent.ai/hackinglabs/cve-2026-the-vulnerability-landscape-when-identity-breaks-and-legacy-code-bites-back/ - Microsoft MSRC — CVE-2026-20841 (official advisory)

- https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2026-20841

- NIST NVD — CVE-2026-20841 detail (CWE, CVSS, change history)

- https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-20841

- Microsoft Learn — Add Microsoft Store Apps to Intune (Store app policy mapping incl. AllowAppStoreAutoUpdate)

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/intune/intune-service/apps/store-apps-microsoft

- Microsoft Learn — Enable attack surface reduction rules (deployment and guidance)

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/defender-endpoint/enable-attack-surface-reduction

- Microsoft Learn — Attack surface reduction rules reference (GUIDs and rule descriptions)

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/defender-endpoint/attack-surface-reduction-rules-reference

- Microsoft Learn — Advanced Hunting schema: DeviceProcessEvents table

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/defender-xdr/advanced-hunting-deviceprocessevents-table

- Microsoft Learn — Advanced Hunting schema: DeviceFileEvents table

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/defender-xdr/advanced-hunting-devicefileevents-table

- Microsoft Learn — Advanced Hunting query language overview

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/defender-xdr/advanced-hunting-query-language